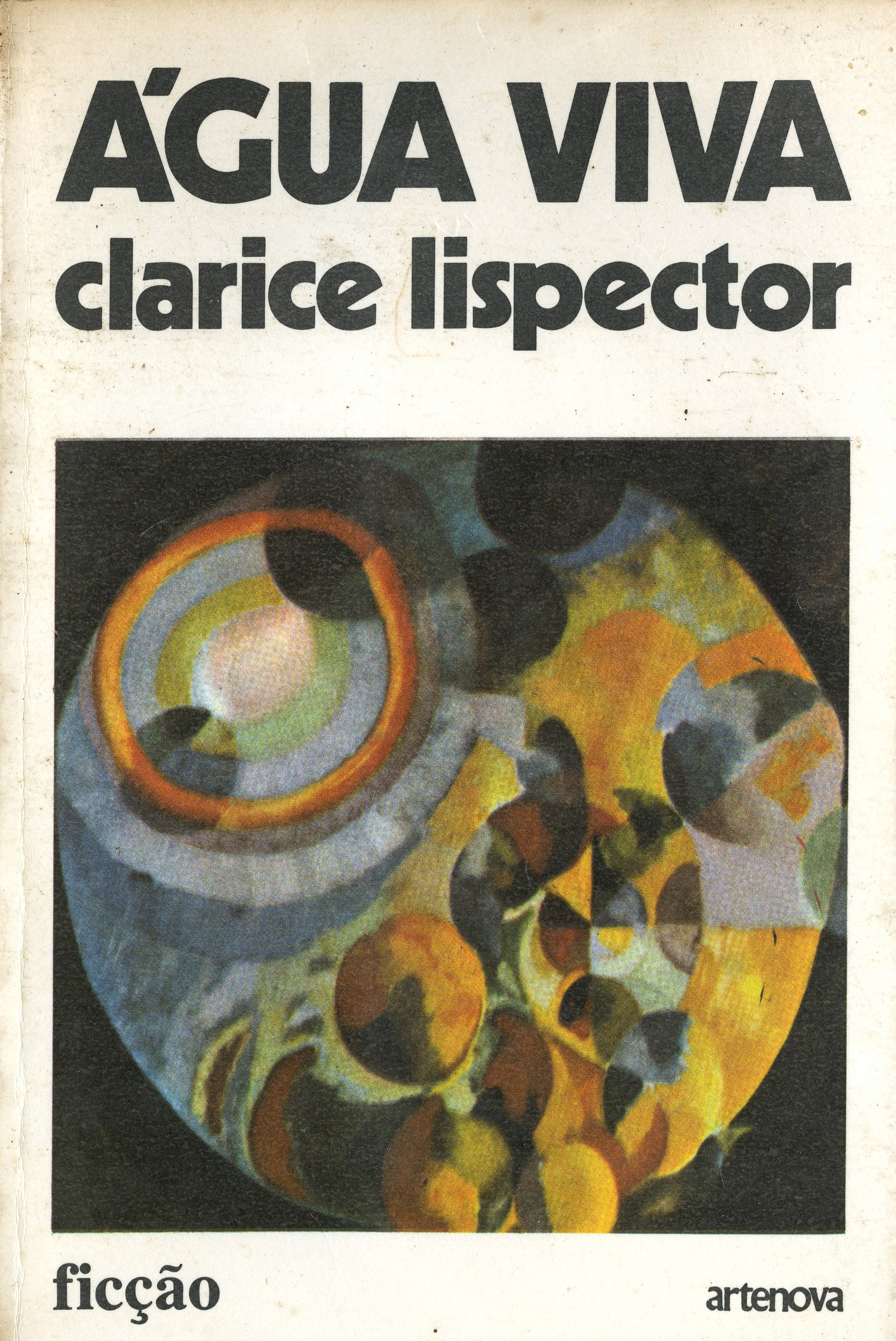

Written by Clarice Lispector in 1971, from (or through) crônicas that had appeared in the press and texts from The Foreign Legion, the long manuscript “Objeto gritante” (Screaming Object) was never published in the original. She edited and rewrote it, transforming it into the work Água Viva (1973), in which she radicalized innovative writing processes with which she had already experimented in previous publications, including in An Apprenticeship or the Book of Delights, in which she engaged in the grafting of journalistic texts.

Água Viva, a hybrid book without a conventional plot, is not a novel, poetry, diary, or philosophical essay, but has fragments of each of these genres. The author disrupts the novel form in a fluid narrative. Ideas and images merge and become a perpetual motion machine. The search for a direct connection among body, thought, and language makes her express herself as someone who paints or performs music outside the realistic standard of representation. For it does not seek the concrete or the analogical as a guarantee of apprehension of the real; on the contrary: the lack of definition of categories such as color, shape, word, the very significant consistency of silence, and the mystery of creation are what lead her to break boundaries in terms of narrativity and the approach to human existence and creation. This engaging and disturbing text seeks the improbable: “Chamber music has no melody. It is a way of expressing the silence.” The reader is led to break reading patterns and to accept the dissonances and movement of the enigmatic and feminine voice.

In Água Viva there is no linear history or central theme. There is an epigraph or motto that provokes the writing: time, the fourth dimension of the “instant-now,” followed by an elusive instant-never. What is said is always fleeting. To apprehend difficult values such as love, death, freedom, loneliness, and religiosity, language must show new faces. Hence the liquid, feminine word, água viva, or “living water,” which nourishes and also burns. “It is itself. I am myself. You are yourself.” New conjugations for new perceptions. A self-nakedness that incorporates transparency and levitation, on the one hand, and also the weight of the body and the soul, on the other. Because even what is unique, and particular, about a person amazes:

“Before the appearance of the mirror, the person didn’t know his own face except reflected in the waters of a lake. After a certain point everyone is responsible for the face he has. I’ll now look at mine. It is a naked face. And when I think that no other like it exists in the world, I get a happy shock. Nor will there ever be.”

ByClarisse Fukelman