The Chandelier (1946), the second novel by Clarice Lispector, was written when the author was living in Europe and completed in Naples, at the end of World War II. One recognizes characteristics in it that were present in Near to the Wild Heart: a plot without a defined structure and a stream of consciousness that favors sensations and the perception of things.

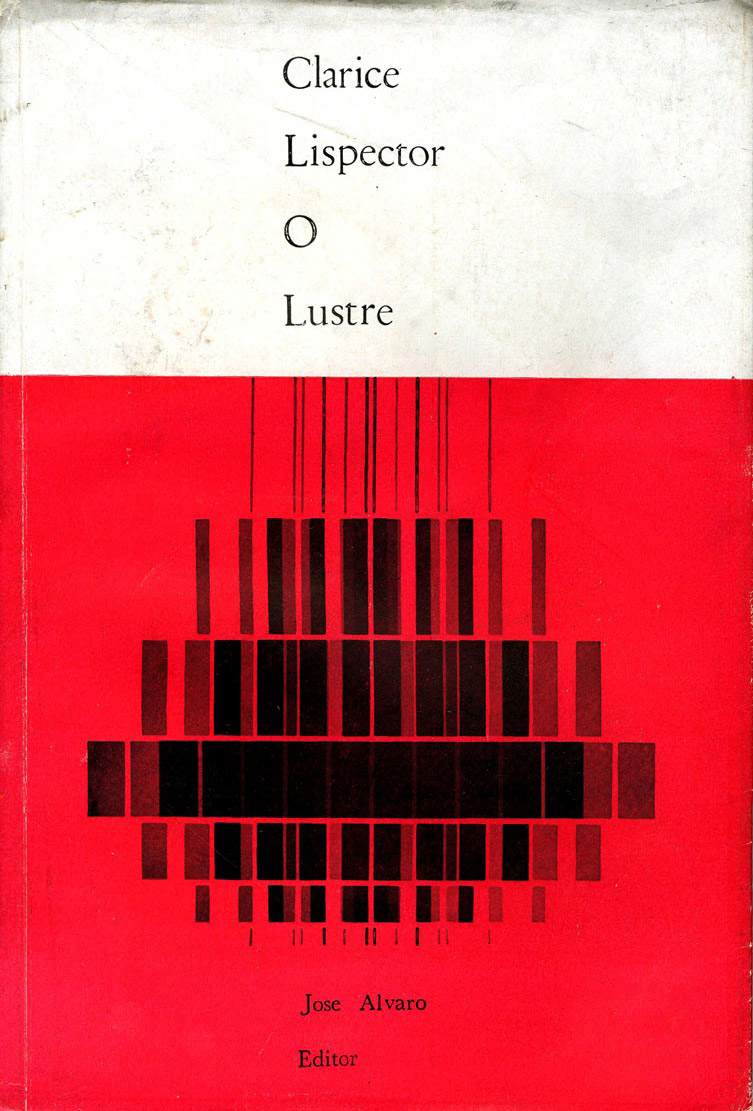

The book tells the story of Virginia, from her childhood on Quieta Farm to her solitary life in the city. The title refers to the decorative element from her father’s house: “There was the chandelier. The great spider would glow. She would look at it immobile, uneasy, seeming to foresee a terrible life. That icy existence. Once! once in a flash — the chandelier shed chrysanthemums and joy. Another time — while she was running through the parlor — it was a chaste seed.” Associated with images of spiders and chrysanthemums (used in funeral rituals), insects and flowers, the chandelier introduces a tragic feminine poetics: it predicts the “terrible life” of characters consigned to isolation, conflict, and lack of affection.

In the novel, death is a presence for the protagonist: her indifference to what life may offer from Eros; the supposed drowning of a man, which haunts her even as an adult; the recollection of when, as a child, she follows her grandmother’s intermittent state between life and death; and the Shadow Society, created by her brother Daniel to torture her. The critic Olga de Sá (Cadernos de Literatura Brasileira [Brazilian Literature Notebooks], Moreira Salles Institute) identifies “a metaphysics of death in Clarice’s fiction;” the “paradigm is perhaps The Chandelier’s Virginia, who dies at the end of the narrative, but whose death is signaled from the beginning.”

The protagonist suffers from physical and existential strabismus. Her limited understanding of the world approaches that of Lucrécia, from The Besieged City. Since childhood, Virginia faints easily, feeling pleasure with the “sensation of nascent flight,” and creates negative relationships with people. In this sense, too, the image of the chandelier evokes a lack, that which does not shine, like Virginia’s opaque existence: “The featherless chandelier. Like a great and quavering cup of water.”

The writer Lúcio Cardoso, a close friend of Clarice’s, considered the book’s title beneath the author’s singularity. She responded: “Precisely due to what you didn’t like, due to its poverty, is why I like it. I’ve never really managed to convince you that I’m poor. (…) Unfortunately, the poorer I am, the more adornments I wear. As soon as I manage a form as poor as I am on the inside, instead of a letter, you’ll receive a little box full of Clarice’s ashes.”

ByClarisse Fukelman