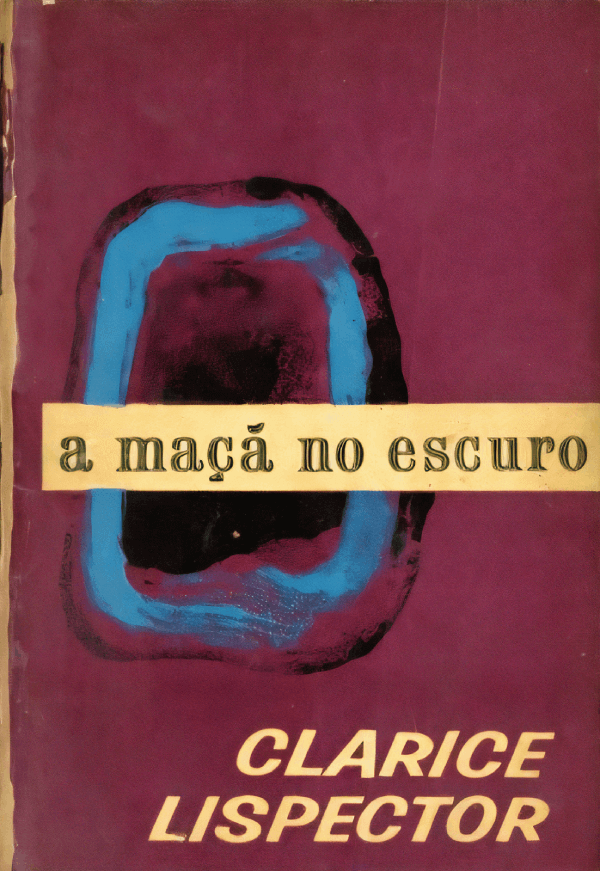

“It’s the best one. I can’t define it, how it is, how it is not… I can only say that it’s much better constructed than the previous ones.” This statement was made by Clarice Lispector on the occasion of the publication of The Apple in the Dark (1961), a novel that, alongside The Passion According to G.H. (1943), marks a culmination point in how she faces the experience of the limit in a more radical manner in her writing. Narrated in the third person, the plot revolves around Martim, who, fleeing a crime he supposedly committed, oscillates between fear and the desire for freedom.

The patient and attentive reader will perceive that it is of little importance whether or not the crime was committed, whether or not Martim will be convicted. From the beginning, the fundamental lines of Clarice’s writing have declared that this will not be a police narrative in the conventional molds, in which the strength of the plot lies in the enigma, the evidence, and the deciphering. The reader will know that Martim’s crime is abstract and symbolic and that, through it, the question of freedom and the difficult construction of a personal destiny will be reached. It is in this problematic place that Martim steps. His crime and his escape appear therefore as a kind of asceticism, as occurs with G.H. in the ritual of devouring a dead cockroach.

The careful symmetrical organization of The Apple in the Dark – there are three chapters, three central and three secondary characters – amounts to one of its structural qualities. In addition, the dark and nocturnal atmosphere opens the door to Martim’s inner night and his permanent state of vigil. A hero one gets to know little by little; a man who wants to give a “a destiny to an enormous emptiness that evidently only a destiny can fill. It is a narrative, therefore, that makes no concessions to the reader, taking her also to the darkness, where everything is created, the darkness of the world.

Scaling step by step the challenge of its narrative structure, one arrives at the center of Lispector’s writing, which, situated at the very limits of language, faces the world to say the unsayable and represent the unrepresentable. In other words, in addition to freedom and destiny as a question, we likewise share with Clarice the sophisticated reflection on writing as a very fragile place that, in its slow rotation, seeks to touch the dark and lyrical face of the world, capturing the lowest and the volatile. Writing as a possibility, as “this unsteady way of picking an apple in the dark, without it falling.”

ByMartha Alkmin