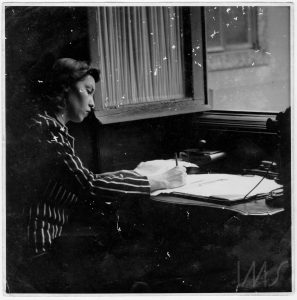

, Clarice is pop. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2013. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2013/02/22/clarice-e-pop/. Acesso em: 09 March 2026.

“Freedom isn’t enough. What I desire doesn’t have a name yet.”

Pop Art Clarice

In: http://www.fotolog.com.br/cleoskull/62867569/

In times of social networks, there has been a migration, like it or not, from the usual and canonized place of artists, musicians, and authors. Readers, intellectuals, or just “quoters” – as is common when its concerns Clarice Lispector – are the main ones responsible for such a movement.

According to a survey done by YouPIX in June 2012, Clarice is the most quoted writer on Twitter. Every day more than 3.5 thousand phrases by the author – or attributed to her – are posted on the microblog. With the small limit of 140 characters for each publication, there is not enough space to include a basic bibliographical reference. When there is an intention on the part of whoever posts the phrases, that is. And if whoever tells a short story adds a period, whoever quotes a phrase adds periods, commas, words, and plots with many errors.

Even on the old Orkut site, there were almost 300 communities dedicated to Clarice Lispector, the biggest of them made up of 317,015 members. Now, on Facebook there are more than twenty apps; thirty pages, which have almost 600 thousand likes, with more than curious titles (originally in Portuguese), such as “Clarice on PMS,” “A Dose of Clarice Lispector,” and “Advice from Clarice.” Some of these pages quote passages from short stories or novels, while others join catch phrases (by Clarice or not) to photos of the author, which today can easily be found on Google, without due concern for copyrights either of the heirs or of the photographers. Not to mention the hundreds and hundreds of blogs in the depths of this Clarice universe.

These numbers may frighten and dismay whoever values “academic exclusivity” in (generally pejorative) opposition to that which belongs to the “masses,” or that is at least popularly renowned.

Clarice’s numbers reveal that her texts do not respect geographical, cultural, or spatiotemporal boundaries, and have been kept very much alive through translations and reeditions, even 40 years after the writer’s death.

In these times of intense subjectivity, of liquid social ties, and of the collective need for realism – or for reality effects – there are those who strictly associate literature and life; as if in reading there were an exaggerated projection of themselves, and by doing so, it were possible to expunge personal ghosts and neuroses. When, in fact, “literature only begins when a third person is born in us that strips us of the power to say ‘I’” (Gilles Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical).

And maybe that is the movement of reading, that of personal association, and not the popularization of works, which diminishes the real power and the permanent becoming that exists in the writing of Clarice Lispector, by subverting her work into simple doses of self-help, into moral lessons, or into unstable predictions of some guru.