, “I'd Like To Write like a Painter”. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2013. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2013/08/06/eu-queria-escrever-como-um-pintor/. Acesso em: 25 February 2026.

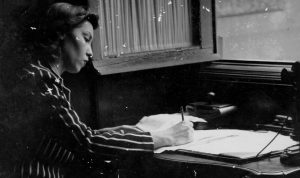

Being a writer was not the first option for Clarice Lispector, as strange as this may seem to us now. Despite having studied law at the University of Brazil, collaborated on editorials, and translated novels, it was fiction writing were she excelled. But one does not live from fiction alone, and Clarice had her affair with painting.

In general, the lines between the visual and literary arts have long been blurred. Some of the greatest icons in literature, such as Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Edgar Allan Poe, and Franz Kafka, in addition to the Brazilians Monteiro Lobato, Rubem Braga, Érico Veríssimo, and Ferreira Gullar, found pleasure in the visual arts. Clarice Lispector also ventured down this path, mainly in the 1970s.

The fascination for painting and for the dynamics that this type of art demanded was manifested in Clarice’s characters and stories, above all in Água Viva, a book published in 1973, in which the theme is approached intensely and experimentally. Painting and writing are in different perspectives of the same plane. A game occurs there, from beginning to end, between an I and a you, between the canvas and the page, between the paint and the letter, which undoes the linearity and serenity to which conventional readers are accustomed. Neither novel, nor poetry, “genre doesn’t have a hold on me anymore,” says the narrator of Água Viva (even though, for the purposes of bibliographical cataloguing, it had to be labeled as a “novel”).

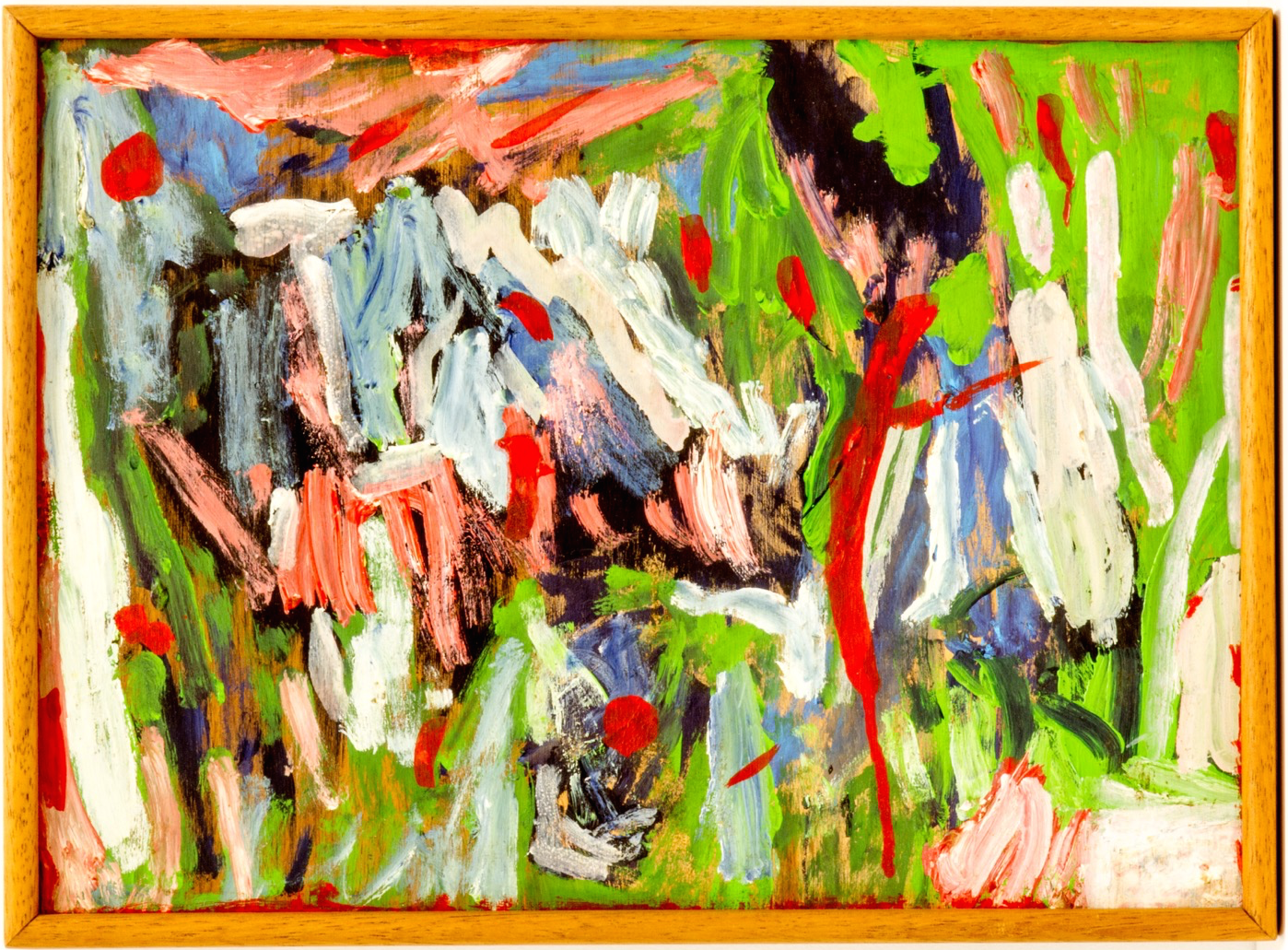

Among the items that make up the Clarice Lispector Collection, which has been at the IMS since 2004, are two of the approximately 20 known paintings by the author: Interior da gruta (Cave Interior) and an untitled work. Although she does not appear to be as skillful at painting as she famously is at writing, in Interior da gruta, Clarice creates a sensation that is similar to the one caused by her stories: discomfort. If at first glance the painting may cause an effect of estrangement, at second glance the observer tends to be overcome by a sort of hypnosis.

With its brown, green, red, and yellow colors vertically painted in gouache, the painting places its viewer in a state of near obtrusion. The image intends to be “behind thought,” a title that would actually be given to Água Viva. Behind thought, close to the non-rational, the wild, the first impulse, divination.

The novel’s narrator says the following about caves:

I want to put into words but without description the existence of the cave that some time ago I painted – and I don’t know how. Only by repeating its sweet horror, cavern of terror and wonders, place of afflicted souls, winter and hell, unpredictable substratum of an evil that is inside an earth that is not fertile. I call the cave by its name and it begins to live with its miasma. I then fear myself who knows how to paint the horror, I, creature of echoing caverns that I am, and I suffocate because I am word and also its echo.

In the second painting, the same dynamic: a profusion of lines, a layering of green, pink, and white, vertical strokes. A patchwork, apparently, just impetus, jumps without rest. Despite the simplicity of the material – gouache on plywood and oil on canvas, respectively – and the rusticity of the strokes, there remains an estrangement similar to that of her writing.

The paintings and the book Água Viva seem to have the same purpose: to discover the “instant-now,” the it, escaping possible definitions. “My painting,” says the narrator, “has no words.” The intention is just to write and draw like a jazz improvisation.