, I’m Talking From My Grave. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2017. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2017/06/07/estou-falando-de-meu-tumulo/. Acesso em: 25 February 2026.

1.

In the year that completes four decades since the release of her last title, The Hour of the Star (1977), the work of Clarice Lispector continues to fully propagate. The book that tells the story of Macabéa – “the story of a girl who was so poor that all she ate was hot dogs (…) it’s the story of a trampled innocence, of an anonymous misery” –, for example, is among the three best sellers in Greece, even surpassing the contemporary Elena Ferrante.

2.

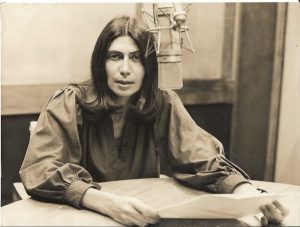

In February of 1977, months before her death, the author visited the studios of TV Cultura, Channel 2, in São Paulo, for a debate and accepted the invitation to be interviewed by the journalist Júlio Lerner, host of the program “Panorama Especial” – this would be her only audiovisual record, which, upon Clarice’s request, would air only after her death, on December 28th at 8:30 in the evening. We reproduce here the complete interview followed by a text written by Júlio Lerner.

3.

4.

From my office at the production of “Panorama” to the studio lobby I have to walk about 150 meters. I am so stunned at the possibility of interviewing her that I can barely organize myself on that short walk. Maybe talk about The Passion According to G.H.… Or who knows, about The Apple in the Dark and Near to the Wild Heart… I call to mind what Clarice has written. Have I read everything? In just five minutes I managed to get a studio to interview her.

It’s 4:15 in the afternoon and I only have half an hour. At 5pm the children’s program goes on live and I have to free up the studio fifteen minutes prior. I’m rushing and before even seeing her the time pressure starts to slaughter me. I won’t be able to prepare anything beforehand, or even talk a little. I won’t even be able to try to create a suitable atmosphere for the interview. I hate Brazilian TV! Just half an hour to listen to Clarice. The technical staff once again was generous and worked hard to make this happen. I look at the clock, I’m not able to get organized, I’m rushing, I look at the clock again. I’m disconcerted, I reach the studio lobby and see her there, ten meters ahead, Clarice standing next to a friend, lost in the midst of the disassembled sets, various equipment, and technicians who speak loudly, in the middle of a great uproar.

I stop in front of her. I’m a little out of breath, I reach out my hand, and I’m pierced by the most unprotected look a human being can throw at a fellow human. She’s fragile, she’s shy, and I’m unable to explain that the problem of time has raised my level of anxiety. Clarice introduces me to Olga Borelli, we enter, and I lead her to the center of the small studio. I ask her to sit in a creamed coffee-colored leather armchair. Clarice holds only a pack of Hollywood cigarettes and a box of matches. I provide an ashtray. The damned spotlights are turned on. Clarice looks at me. Clarice’s eyes interrogate me. I have only one camera. Clarice’s eyes plead, Olga settles in an unlit area, Miriam, the program’s intern, arrives and remains huddled and silent, the heat is getting unbearable and the air-conditioning is not adjusted. It’s only 4:20, Clarice tries to tell me something but I don’t talk to her, worried about adjusting a lighting issue, the breath of the furnace already reaches all of us, it must be 50 or 60 degrees Celsius in the studio, cursed TV, blessed Third World TV that allows me to be face to face with her now. Clarice looks at me squeamish, frightened, and her look asks me to reassure her.

“OK, Júlio, all set,” the metallic voice comes from the loudspeaker. I ask the entire team to leave, camera assistant, gaffer, studio assistant, thanks. Clarice realizes she’s fallen into a trap and there’s no turning back. I request silence and after about 10 seconds “recording” echoes.

We haven’t spoken before and I have only 23 minutes. I’m completely disconcerted, I remain silent for a minute, staring at Clarice. I’m hollow, empty, I don’t know what to say. Clarice looks at me, curiously but watchfully, defensive. I’m the lord of the castle and — arrogant — hold the key to this prison. No one can enter or exit without my express consent. Everyone must submit to my authoritarian will.

The furnace is burning, my heart is racing, my mouth is dry, and underneath these thousand tyrannical suns I’m the greatest of tyrants. The interview starts. The interview progresses. Her ocean-blue eyes reveal loneliness and sadness. Clarice is naked, there’s no forgiveness. Clarice is now cloaked, she lets herself be held, but soon she escapes, and returns, and catches me, and suggests to me the distant, the unspeakable, and then does not speak. And when I don’t expect any more, she speaks again. I do an anti-interview, pauses, silences. Clarice is now fleeing to an uninhabited, unreachable galaxy, but then she returns and, tolerant, supports all my limitations.

I think she’ll get up at any moment and say: “Enough!” Clarice senses that behind my seemingly comprehending smile and my smooth talk lurks a diabolical being who is a self-styled “reporter” and who wants to possess her private life. Her body expresses fears, she pulls away from me, but again attracts me, her legs cross and uncross unceasingly and telegraph that suddenly she will be able to get up and leave.