Roncador, Sônia. Clarice, Mistress. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2025. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2025/04/01/clarice-patroa/. Acesso em: 17 February 2026.

The lunch was exquisite, a million miles from any idea of hours spent laboring in the kitchen: before the guests arrived all the scaffolding had been removed. (LISPECTOR, 2022)

I

In August 1967, Clarice Lispector (1920-1977) would accept a proposal from her journalist colleague Alberto Dines, who was aware of her precarious financial situation (“Clarice jornalista,” p. 8), to write chronicles on varied subjects for a weekly column in the Jornal do Brasil.1 Journalism had already served as an opportune way (sometimes the only one) to promote and publish part of her fictional work for almost two decades. Furthermore, according to her biographers, her journalistic activity guaranteed some financial support, above all in the years following her definitive return to Brazil, after fifteen years in exile married to a diplomat. Nonetheless, her “parallel career” as a chronicler and her participation in the lucrative business of columns written by celebrities represented a source of moral stress for the author – who was at the same time concerned about her intellectual reputation and about her form or “style” of writing fiction, which, in her view, the exercise of chronicling could corrupt. In one of her first chronicles for the Jornal do Brasil, “Undying Love” (September 9, 1967), one observes, above all, the author’s discomfort in “writing as a way of earning money” (Too Much of Life), which would compromise her dilettante view of literature and, above all, the myth of the non-professional woman writer, which many intellectuals of her generation, for one reason or another, ended up reinforcing. Such factors, therefore, would reinforce a kind of “rhetoric of self-disqualification” as a chronicler in several of her contributions throughout her six years at that newspaper (1967-73), in addition to the need to separate her “true” literary vocation from the “new” role of chronicler.

In this text about Lispector’s former domestic servants who were regularly part of the “little conversations” or “light impressions” in her written column (her terms), Lispector’s conflicts as a chronicler would gain a thematic nuance that is especially revealing of her positionality as a white, middle-class woman, who was at the same time aware of the role of her employer class in preserving the culture of domestic servitude that has persistently and profoundly shaped the modus operandi of paid domestic service in Brazil. As sociologists Raka Ray and Seemin Qayum (2009) argue: “Those living in a particular culture of servitude accept it as the given order of things, the way of the world and of the home […] servitude is normalized so that it is virtually impossible to imagine life without it, and practices, and thoughts and feelings about practices, are patterned on it” (Cultures of Servitude, p. 4). Lispector takes a critical stance towards the culture of servitude that structures the family life of the Brazilian middle class; at the same time, she makes use of these personal narratives about her intersubjective relationships with former domestic servants as a means of revealing her uncomfortable social position due to enjoying privileges that are morally incompatible with the position of a politically committed intellectual with which she and many writers of her generation identified. In some of these chronicles, as we will see, Lispector tries to compensate for such conflicts by associating herself with an ethics of care as a way of relating to her maids. Nonetheless, this affective gesture never materializes into concrete actions aimed at improving the degrading conditions of her maids, thus revealing a truth expressed in other chronicles of hers about domestic servants: conflicts can be mitigated, but never resolved.

II

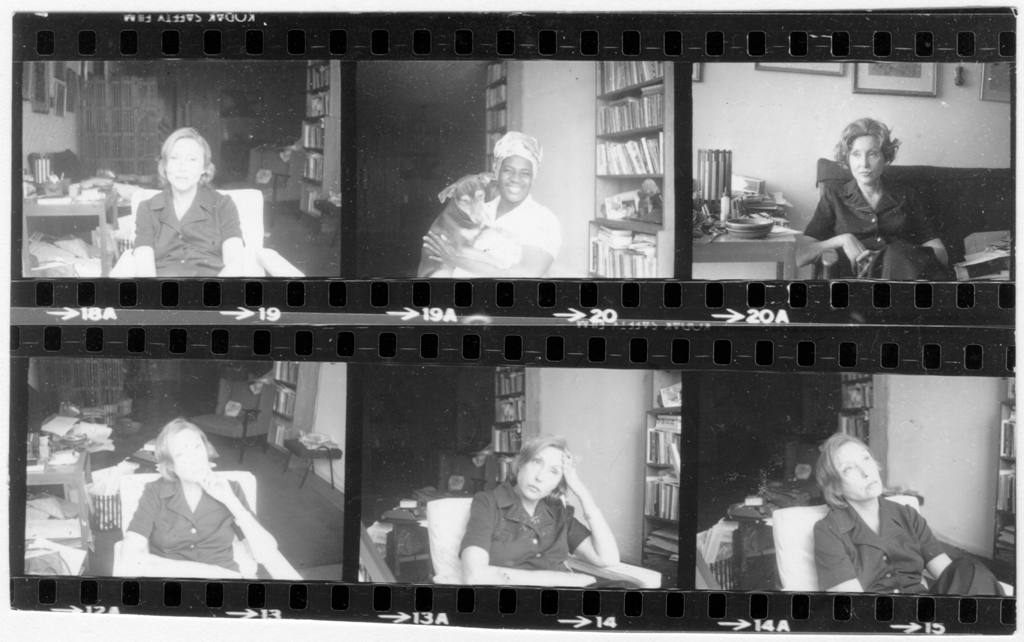

Latin American chroniclers have been studied in their mediating role in the processes of formation, problematization, and consolidation of social practices and identities in urban spaces, especially based on their interest in “commenting on the way that we live, the customs and moral values in the social contract of big cities” (“Lispector, cronista,” p. 98).2 The chronicle in Brazil having established itself as a “writer’s genre,” but without losing the epistemological authority of journalism, chroniclers are equally recognized for “standing out in their recording of the everyday in all of its urgency, in their sensitivity to the fascinating diversity of life, in their construction of complete scenes instead of dryly reporting the news” (“Lispector, cronista,” p. 98). In the particular case of Lispector’s chronicles, I am particularly interested in the “construction of complete scenes” of everyday intersocial/racial relations in urban and bourgeois domestic spaces. The set of her chronicles republished in the collection Discovering the World (1984) reveals that, among her experiences of sociocultural diversity in the urban context of Rio de Janeiro, those that were most often recorded in her weekly column were her relationships with distinct former domestic servants (at least ten chronicles in the aforementioned collection are dedicated to the topic).

The frequent allusion to domestic servants in the urban environment of her chronicles demonstrates what is a reality for many middle-class families in the country: incorporated into the intimate environment of the home in the condition of a “domesticated outsider” (CLIFFORD, 1988), the domestic servant constitutes the most lasting and personal relationship that a member of the middle class allows themselves to establish with poverty. The fact that Lispector made use of the space of her Saturday column to produce her public image as a Brazilian intellectual in the face of unresolved social tensions and traumas certainly had an impact on the repertoire of the domestic characters selected for these chronicles. In a sense, her written column served to negotiate and justify her fame as an introspective and formally experimental writer, in a period of cultural history when writers felt compelled to produce texts with explicit political themes – a result, as we know, of the authoritarian military regime that was established in the country for 21 years. On the other hand, as I seek to demonstrate, the author faced the challenge avoided by other writers of her generation and social class: that of exemplifying, through her personal chronicles about former domestic servants, the contradictions inherent in her self-promotion as a socially responsible intellectual in the face of her position of authority and socio-racial privileges.

In a chronicle from her collection The Foreign Legion (1962), “Literature and Justice” – a response to the accusations received in those years for the lack of social and political commitment in her literature –, Lispector argues that the fact that she did not know how to approach “‘the social thing’ in a ‘literary’ way” did not reflect, in her case, a lack of feelings of “justice,” obligation, and social responsibility. “For as long as I’ve known myself,” writes the author, “social issues have been more important to me than anything else: in Recife, the shantytowns were my first truth” (Too Much of Life). The argument is not new that Lispector, contrary to her own self-defense, actually knew how to approach the social problem “in a ‘literary’ way,” although this theme was more frequent and relevant in her literary work in the 1970s. In another chronicle published in the Jornal do Brasil, “What I Would Like to Have Been” (November 2, 1968), Lispector would once again associate the impact of the social drama of the poor with her childhood forays into the outskirts of Recife, as she would also dissociate her literature from her inner feeling of social justice. In this second chronicle, however, she introduces the mediating figure of a domestic servant, without whom her trips to the shanty towns would not have taken place: “In Recife, on Sundays, I would go and visit our maid in her house in the slums. And what I saw made me promise myself that I would not allow that to continue. I wanted to act” (Too Much of Life). As both chronicles reveal, the ethical awareness acquired in childhood (which earned her the nickname “the protector of animals” in her family, p. 217) would keep compelling her to “social action” as an adult – a compulsion transformed into a sense of responsibility (and, as we will see, a maternal obligation) that her activity as a writer, according to her, did not allow her to alleviate: “And yet what did I end up being, and from very early on too? I ended up being a person who seeks out her deepest feelings and finds words to express those feelings. That is very little, very little indeed” (Too Much of Life).3

Moving between two socially opposed worlds, the domestic servant emerges in many historical and subjective circumstances as a threat to the family and social order of the employer class.4 In Lispector’s chronicles, the domestic servant acts as a double-edged sword: she is the intermediary figure – the “domesticated outsider” – who leads the author to a traumatic, yet edifying, social revelation (a role that Lispector knew how to explore so well in the figure of the maid Janair, in the novel The Passion According to G. H.). On the other hand, although she herself is a woman of social and cultural origins distinct from the author, the domestic servant is also the one who injects the drama of social exploitation into the “protected” domestic world. Furthermore, as Lucia Villares argues, the figure of the domestic servant likewise forces the author to confront herself with the problem of racial difference and hierarchy; that is, to place herself in “a position where her whiteness becomes visible” (“Welcoming,” p. 80).

In one of the many chronicles in which Lispector alludes to domestic servants, “Dies Irae” (October 14, 1967), she writes: “And having maids—let’s be honest here and call them servants—is an offense against humanity” (Too Much of Life). The tone of “rage” in this passage reveals the difference between the treatment given to domestic servants in the “women’s” columns that she wrote (1952/1959-61) and that which was predominant a few years later in the weekly column of the Jornal do Brasil.5 In both contexts, the author focuses on the difficulties inherent in the mistress-maid relationship, or the domestic disencounters between women of two classes, who were generally of distinct races, although she presents opposite reasons for such conflicts: unlike her columns for women, in these later chronicles, Lispector associates the difficulty of the relationship not with the defects in the maid’s personality and services, but precisely with her servile condition.

In another chronicle in the Jornal do Brasil, “What Lies Behind Devotion” (December 2, 1967), Lispector problematizes the idealized view of “devotion,” or servility, as an expression of love, gratitude, and loyalty from the working class; one can, as she herself argues, be devout while feeling “hatred.” In the chronicle in question, Lispector refers specifically to the domestic characters in Jean Genet’s play The Maids, which she had just seen. “It really upset me,” the author emphasizes, thus revealing to her readers the trauma of this experience: “I saw how maids feel inside, I saw how the devotion we often receive from them is filled with a mortal hatred” (Too Much of Life). According to Lispector, “their long enslavement to masters and mistresses is too ancient to be overcome,” and therefore, “[s]ometimes that hatred remains unexpressed, and takes the form of a very particular kind of devotion and humility.6 Such a reflection makes her think, for example, of the “unexpressed” hatred of a former domestic servant, the previously mentioned Argentine Maria Del Carmen: “She pseudo-adored me. Precisely at those moments when a woman is looking her worst—for example, getting out of the bath with a towel around her head—she would say: ‘Oh, you look lovely, Senhora.’She overflattered me.” (Too Much of Life).7

Nonetheless, without diminishing the value of narratives of social hatred and the censored forms that this feeling may take (pseudo-adoration, excessive flattery), I agree with Marta Peixoto (2002) that the author “reserves for her fiction – especially A paixão segundo G.H. – a view of that relationship that is more critical and fraught with negative emotions” (“Fatos,” p. 111). Perhaps out of attention to the “conventions” of the chronicle genre (for her, “light impressions,” or entertainment narratives), and above all to free herself from possible embarrassments that the role of mistress reserved for her, Lispector elaborates in her weekly column distinct strategies to “attenuate differences and bring out unexpected similarities” with her (former) maids (“Fatos,” p. 113). Accepting her sister Tania Kaufmann’s humorous suggestion that “we all get the cook [or maid] we deserve” (Lispector, Too Much of Life), the author gifts her readers’ Saturdays with some fun facts about her clairvoyant cook, the former maid who “was having psychoanalysis—I mean it” (Too Much of Life), or “[a]nother maid, who went with me to the United States, stayed on when I left in order to marry an English engineer” (Too Much of Life). Furthermore, according to Peixoto (2002), Lispector’s “lyrical and gentle portraits” of the domestic servant – who “accepts differences of experience and values and pardons discreet thefts” (“Fatos,” p. 115) – likewise reveal the predominant treatment of maids in her chronicles for the Jornal do Brasil: the writer speaks of the “[g]uilt, tensions and estrangement” (“Fatos,” p. 115) arising from her countless relationships with maids, although she tries to overcome them through humor or lyricism.

To “attenuate” the social differences brought into her domestic world by a “maid,” she tends to highlight certain eccentricities in her the personality of her maids that divert the focus from the exploitative relationship to less embarrassing areas of this daily intersocial/racial interplay. However, if on the one hand she frees her maids from certain negative stereotypes (some of which are used in her columns for women), on the other, she ends up fixing them in a new taxonomy of personalities and quirks. Types such as the comic cook, maids with an artistic vocation and a keen sense of human psychology, or even “unconscious” ones (due to psychotic episodes or brief “distractions”) end up integrating themselves more into the fictional universe of her characters than into the embarrassing domestic space of social differences. Lispector’s attempts to “attenuate” such differences and “bring out unexpected similarities,” however, do not always seem to her like a project that is possible to undertake. In a passage from her manuscript “Objeto gritante” [Screaming Object], Lispector, for example, anticipates the shock of incomprehension that her “backcountry” maid, Severina, would feel when she sees the sea for the first time: “She may feel bad. Because the sea is not understandable. It is felt and is seen. I am putting myself in the shoes of this maid named Severina. And being her, I get really frightened. I must have seen the sea for the first time. But I don’t remember [….]” (“Objeto gritante,” p. 71).8 As is known, the sea constitutes an important motif in Lispector’s work; in her writing, a simple act of entering the sea can become a solemn ritual. Among other factors, the sea exerted a true fascination on the author by stimulating her reflections on the possibilities of maximum self-expansion and of true contact with non-human existences. In the aforementioned passage, Lispector projects onto her maid’s unprecedented encounter with the sea a reaction similar to her own or that of her literary characters, only to later abandon this projection: “I will fire Severina: she’s too empty. I didn’t have the courage to take her to see the sea: I was afraid of feeling for her what she didn’t feel. She’s from the Northeast and is empty from so much suffering.” (“Objeto gritante,” p. 74).9

It is, therefore, from the accounts of the “surprisingly” talented, perceptive, and sagacious maids that the author creates the typical panorama of the domestic servants who frequent her chronicles. On the one hand, Lispector highlights the poetic meaning and effect of phrases said by the domestic servants in their daily interactions, as is the case, for example, of her maid Rosa, in “The Italian Girl” (April 4, 1970; previously published in The Foreign Legion as “An Italian woman in Switzerland”): “I really don’t know why I like autumn more than the other seasons, I think it’s because in the autumn things die so easily [….] She also says: ‘Have you ever bawled your eyes out for no reason? Well, I have! And she roars with laughter” (Too Much of Life).10 In “One Thing Leads to Another” (May 16, 1970), Lispector is moreover surprised by her cook “humming a lovely tune, a kind of harmonious plainchant. I asked her who had written it. She replied: oh, it’s just some nonsense I came up with myself.” (Too Much of Life). Nonetheless, as happens with other projects to increase the aesthetic value of popular expression, in these chronicles, Lispector has to make use of her artistic authority to add to the “creative” words or “harmonious” melodies of her employees a symbolic value unrelated to their intention. As she herself admits, with respect to this cook whose “mouth can sing,” “she [the maid] didn’t know she was creative” (Too Much of Life).

In one of her most interesting chronicles on the subject of domestic servants, “Sunday Tea” (March 7, 1970; published in The Foreign Legion under the title “The tea-party”), Lispector also highlights the poetic impact (albeit involuntary) of several isolated phrases that she attributed to the maids that she had had throughout her life. In this chronicle, the author imagines herself as the host of a tea party offered to “all the maids who have ever worked for me” – “[a]lmost like a tea for ladies, except for there would be no complaints about maids” (Too Much of Life). Aside from the ironic tone of the comparison, the narration of this imagined social gathering does not intend to realistically portray this quasi “tea for ladies.” First of all, the imagined setting for the tea party would be Rua do Lavradio, where her character Macabéa would later walk in The Hour of the Star (1977). Furthermore, it mixes elements of a peripheral urban setting (the port area of Rio) with “a certain air of theater of the absurd” (Arêas, “Peças,” p. 563):11 at first the maids “would sit, hands folded on their laps [….] Silent” (Too Much of Life), and then, “brought back to life, the living dead,” they would begin to “recite” phrases that were once said spontaneously and that, through the effect of humor, beauty, banality, revelation, or even discomfort, were retained in the author’s memory: “Silent – until the moment when each one would speak and then—brought back to life, the living dead, would recite what I remember them saying” (Too Much of Life).

Lispector, for example, once again “remembers” what the aforementioned Italian maid, Rosa, had said to her upon hearing the comment of a stranger on the street about the simultaneous fall of the last autumn leaves and the first snow: “‘It’s raining gold and silver.’ I pretended not to hear him, though, because, if I’m not careful, men can do whatever they like with me.” (Too Much of Life). Sometimes, however, she confesses that a single banal phrase, such as “I like movies about hunting” was “all that remains to me of an entire person” (Too Much of Life).

It is likely, on the other hand, that from her daily interactions with domestic servants, the author learned that in the banality of certain phrases are found hard truths, such as “When I die, a few people will miss me. But that’s all” (Too Much of Life). One observes in another phrase “recited” by one of her former domestic servants the revelation that maternal love can manifest itself in the form of a violent desire, which is not always repressed (a theme in her famous short story “The Foreign Legion”): “He was such a lovely little boy that I almost felt like spanking him” (Too Much of Life). But it is from the “oldest of them all,” the maid whose “tenderness always had a bitter edge,” that Lispector seems to draw the most profound lesson – “to forgive cruelty lovingly”—, which is for her a product of her humiliating servile condition:

Here comes Her Ladyship,” and the oldest of them all stands up, the one whose tenderness always had a bitter edge and who taught us early on to forgive cruelty lovingly. “Did Her Ladyship sleep well? Her Ladyship likes her luxuries. She knows what she wants too—she wants this, she doesn’t want that. Her Ladyship is white. (Too Much of Life)

The aesthetic effect of a “certain air of theater of the absurd,” as well as the emphasis on the performance of reciting the phrases, demonstrate that, if on the one hand the author proposes to “give voice” to the maids by quoting phrases such as the aforementioned ones, on the other, she introduces such phrases in a decontextualized way – which intensifies their poetic force but dilutes their practical and, in some cases, political function. Furthermore, limited by her memory, Lispector recuperates from her interactions with various domestic servants only those phrases that would manage to reduce her uncomfortable and guilt-ridden social distance. In a sense, she “resurrects” through this curious tea party of ghostly maids the (verbal) fragments of this interaction that constitute the general picture of the domestic servants that the author would have liked to have, and to “deserve.” The singularity of Lispector’s domestic servants did not go unnoticed by the writer Paulo Mendes Campos, in whose chronicle “Minhas empregadas” [My Maids] he comments, with a certain jealousy, on the “subtleties” (p. 186) or “a certain finesse of psychological reactions” in his friend’s domestic servants, when he, on the contrary, saw himself “unfortunately destined to have maids who were a bit, so to speak, feeble-minded” (Campos, “Minhas empregadas,” p. 185). According to Campos, “often saying things that recall her characters,” many of Lispector’s domestic servants end up “imitating her art” (“Minhas empregadas,” p. 185).12 The last paragraph of “Sunday Tea,” actually a long collage of parts of the phrases recited at this pseudo “tea for ladies,” can be applied to Campos’ comment: on the one hand, Lispector highlights, through the speech of her maids, certain invisible aspects of their “psychological conditions;” on the other, she manipulates the speech of the domestic servant (by selection, composition, cuts, decontextualization) in such a way as to emphasize her own aesthetic and thematic preferences much more than the possible tensions that this speech would certainly generate in its real context:

Food is all a matter of salt. Food is all a matter of salt. Food is all a matter of salt. Here comes Her Ladyship: I hope you get what no one can give you, but only when I die. It was then that the man said it was raining gold, yes, what no one can give you. Not unless you’re afraid of standing in the dark, bathed in gold, but alone in the darkness. Her Ladyship likes her luxuries, but the poor variety: leaves or the first snow. Savor the salt that you eat, don’t harm any lovely little boys, don’t giggle when you ask for something, and never pretend that you didn’t hear if someone should say: Listen, woman, it’s raining gold and silver. Yes. (Too Much of Life)

In her weekly chronicles about domestic servants, Lispector thus recognizes the tensions of this intersocial/racial domestic coexistence, and although she is overcome with embarrassment and guilt, she tries to dissolve such tensions through the narration of very humorous situations. In addition, the author values the perceptive and creative potential of domestic servants as a means of diverting to aspects of this daily relationship that could alleviate the embarrassing social inequality and their servile condition. Nonetheless, she sometimes resents not being able to perform this “redeeming” gesture, as is the case with the aforementioned domestic servant Severina, the “empty” Northeastern woman, who, perhaps for reinforcing (instead of diminishing) her guilt, she ends up firing: “I want a maid who’s completely alive even if she gives me more work,” the author justifies. “I can’t have a dead thing at home” (“Objeto gritante,” p. 75).13

III

Various chronicles by Lispector reveal, however, that a “maid who’s completely alive” can be equally problematic, not only because she “gives me more work,” but also because she disrespects the protocols of servile behavior and the social boundaries that the author, although guilty, is not interested in breaking. For example, in the chronicle “The Silent Girl from Minas Gerais” (November 25, 1967), the maid Aninha seems to overcome her “empty,” half-dead state by means of an unusual interpellation of her author/employer; in this case, a request to Lispector to lend her one of her books. The sequence of scares, hesitations, pretenses, and finally, refusals on the part of the author reveals that she also does not wish to replace a relationship of social exploitation (despite the embarrassment that this imposed on her) with a less “hierarchical” social contract between author and reader: “I didn’t want to give her one of my books to read, because I didn’t want to create an overliterary atmosphere at home, and so I pretended I had forgotten” (Too Much of Life).

At the beginning of the chronicle, mistress and maid silently perform the domestic activities that at the same time define them in the hierarchical organization of domestic service and separate them physically and socially: “One morning, she [the maid] was tidying a corner of the living room, and I was in another corner, doing some embroidery” (Too Much of Life). The aforementioned request from the maid, although made in a “muffled” voice, nonetheless comes not only to disturb the comfortable silence of that morning, but also to bring to light the embarrassing social difference: “I felt embarrassed,” reveals the author. “I was frank though: I told her that she wouldn’t like my books because they were rather complicated.” (Too Much of Life). The use of humor at the end of the chronicle reveals, I repeat, that the author’s recognition of the tensions and disencounters inherent in her day-to-day life with the maids does not take place without, at the same time, her trying to attenuate (but not resolve) such tensions: “It was then, as she continued her tidying, and in an even more muffled voice, that she said: ‘I like complicated things. I don’t like sugared water.’” (Too Much of Life). Lispector would reserve the narration of the continuation of this brief interlude with her maid Aninha for the aforementioned chronicle “What Lies Behind Devotion,” published on the Saturday following “The Silent Girl from Minas Gerais.” To compensate for her refusal to comply with her maid’s request, “because I didn’t want to create an overliterary atmosphere at home,” the chronicler, “[i]nstead, I gave her a detective novel I had translated” (Too Much of Life). However, despite the author’s prejudices, the chronicle reveals that the maid Aninha’s literary preferences did not seem to include a type of literature that Lispector considered more accessible: “I’ve finished reading that book,” says Aninha, referring to the detective novel translated by Lispector. “‘[I] liked it, but I did find it a bit childish. I’d like to read one of your books.’ She’s persistent, the girl from Minas Gerais. And she actually used the word ‘childish’” (Too Much of Life). It is possible, without a doubt, to relate these passages about Aninha’s literary tastes to the negative criticism that Lispector received about the hermetic nature of her literature; in other words, the author may have used the responses, invented or not, of a maid to ironically retaliate against the opinion then current among readers and some critics that her books were excessively obscure and unpopular. Nonetheless, her refusal to share her literary production with a maid reveals, on the other hand, that the author, although resentful of the critical attacks, also did not seem interested in promoting herself as a writer who was read and appreciated by members of different social classes.14

The maid Aninha would be the theme of two more chronicles for her column in the Jornal do Brasil: “God’s Sweetnesses” and “More of God’s Sweetnesses” (December 16, 1967). But, unlike the previous chronicles about this “silent girl from Minas Gerais” who liked to read complicated texts, here humor and irony are substituted by lyricism. Lispector would choose the same lyrical tone for another chronicle about (former) maids, “Gentle as a Fawn” (January 27, 1968). In both chronicles, the change or substitution of tone constitutes, in my opinion, the materialization of a maternal feeling, which the author would reserve only for a few maids, particularly those who are associated with the aforementioned “unconscious” type. In “Gentle as a Fawn,” the “unconsciousness” of the maid in question, named Eremita, is associated with her moments of mental “repose” or “distraction:”

For [Eremita] had moments of distraction. Her face took on a smooth mask of impassive sadness. A sadness more ancient than her nature. Her eyes became vacant; one might even say a little cold. Anyone near her suffered without being able to help. All one could do was to wait. (Selected Crônicas, p. 19).

In “God’s Sweetnesses,” as I will demonstrate, the mental “distraction” of the maid Aninha acquires a pathological aspect, although at the same time “sweet” and “crude.”

It is valid, on the one hand, to associate Lispector’s special interest in her “unconscious” domestic servants with her long trajectory of exploring and valuing irrational modes of experience, or in the terms of the narrator of Água Viva, what one experiences when one courageously frees oneself from the limits imposed by “reasoning” to acquire, “beyond thought,” the paradoxical vision of the formless: “but now I want the plasma – I want to eat straight from the placenta” (Lispector, Água Viva, p. 3). In the context of her chronicles about domestic servants, on the other hand, this experience inspires a particular interest because it is presented as a possibility of redemption from the servile condition of this social group. Perhaps this is the reason why, contrary to the expectations of her employer class, the chronicler, in “Gentle as a Fawn,” shows herself more interested in the almost not at all productive “distractions” or “reposes” of the maid Eremita than in her services. Furthermore, even when reintegrated into the order of capitalized domestic chores (e.g. washing clothes, mopping the floor, hanging the laundry), Eremita remains above her status as a servant, given that such tasks are transformed, in this text, into a simulacrum of a primitive ritual of worship “to other gods.” In confluence with other chronicles, Lispector describes the distracted moments of Eremita, “this strange infanta,” as a dangerous descent into her inner depths, or rather, to the “profundity” and “darkness” (Selected Crônicas, p. 12) of herself (“Yes, she had hidden depths”).

In the chronicle “State of Grace—A Fragment” (April 6, 1968), this descent constitutes an “entrance to that paradise” (Too Much of Life); here, it is a “short cut into the forest” (Selected Crônicas, p. 12). According to the chronicler, upon returning from the “forest,” Eremita set herself to subversively performing her duties, since by appearing (simulating?) obedience to her mistress, she actually “took care to serve from a much greater distance, and to serve other gods:” “For anyone looking closely would have noticed that she washed clothes in the sun; that she mopped the floor – drenched by the rain; that she hung the sheets – out in the wind” (Selected Crônicas, p. 12). “Gentle as a Fawn” is, in this sense, one of her most transgressive representations of the social order, where the hierarchical mistress-maid relationship is established; at the same time, ironically, this text constitutes one of the most comfortable types of domestic servant in her chronicles, where even the social signs associated with Eremita – hunger, “the rudeness typical of maids,” fear, and “petty theft” – are naturalized, or devoid of a political-ideological meaning, to serve the mysterious and insubjugable image of the girl: “There was nothing hard about her, there was no suggestion of any perceptible law. ‘I was afraid,’ she would say quite naturally. ‘Boy, was I hungry!’ she would exclaim, and for some strange reason there was never any more to be said” (Selected Crônicas, p. 12).

It is only in the chronicle “God’s Sweetnesses” that Lispector, on the contrary, reveals the frustrations and failures implied in the attempt to compose an empowered image, redeemed from guilt, of her maids. At the beginning of “God’s Sweetnesses,” Lispector addresses her readers, in an almost accusatory tone, to point out their indifference to, and neglect of, her maid Aninha, despite only two weeks having passed since the publication of “What Lies Behind Devotion:” “You will probably already have forgotten my maid, Aninha, the silent girl from Minas Gerais, the one who wanted to read one of my books even if it was complicated, because she didn’t like ‘sugared water.’” (Too Much of Life). I am drawn by the ambivalence of this passage by Lispector, which denounces the neglect of her readers (a reflection, certainly, of a dominant culture of indifference to domestic servants), while acknowledging, on the other hand, their admiration and loyalty as constant readers of her columns; such a passage reveals that Lispector, a few months after her first chronicle in the Jornal do Brasil, assumed that she had achieved a loyal readership, who regularly followed the texts of her column on Saturdays. At the same time, it caused her some embarrassment to benefit from a social system in which writers received the affection and loyalty of a public that, for its part, was incapable of treating its maids in the same way. Furthermore, the author denounces the forgetfulness of the readers, which contrasts with her qualities as an affectionate mistress and the dominant lyricism in this text: “what I did not perhaps mention was that, in order for her to exist as a person, she needed you to like her. You may have forgotten her, but I will never forget her” (Too Much of Life).

The chronicler “will never forget” a morning when Aninha had returned home from a supposed trip to the market, with the money still crumpled in one hand, and her shopping bag full of bottle caps and pieces of dirty paper in the other, to “decorate my [her] room.” Examined by a resident doctor at the Pinel Institute, the girl was promptly diagnosed as a victim of a psychiatric episode and committed, not without the intervention of some of the author’s influential friends. The unique way in which Aninha’s pathology is described reveals that, despite the affection and care of her mistress, it was necessary for the maid to go crazy in order to effectively “exist as a person.” First of all, Aninha (whom the author, without knowing why, insisted on calling “Aparecida,” or the one who “appeared”) “was somehow a little more aparecida, as if she had taken a step forward” (Too Much of Life). Furthermore, “now her very expression was childish and clear:” “I’ve never seen such sweetness,” the author reinforces (Too Much of Life). The brief dialogue between Lispector and the psychiatrist, “whom I later learned was Professor Artur” (Too Much of Life), nevertheless, snatches the author away from her world of “childish expressions” and “sweetnesses” to the social reality of that which only to her “was somehow a little more aparecida:” Aninha, actually, was nothing but a servant to the others. Upon learning of the author’s identity, the resident psychiatrist – himself a reader of Lispector – was “far more interested in me than in Aninha” (Too Much of Life). There is a repetition, at the level of the story, of the same feeling of discomfort that sometimes admiration (in this case, from her readers) can cause, above all when it is based on an unfair social hierarchy: “he added politely, effusively, far more interested in me than in Aninha: ‘It’s such a pleasure to meet you.’ And foolishly, mechanically, I responded:’Oh, me too.’” (Too Much of Life). On the other hand, as Debra Castillo (2007) argues, this unbalanced exchange of effusions and sympathies (on the part of the doctor) and mechanical and shaken responses (from Lispector) makes evident the author’s own unstable social position, which is conditioned by “suppositions of social class and gender” (Castillo, “Lispector, cronista,” p. 105).15 In fact, the question “Are you a writer?” – first asked by the maid Aninha and then by the resident doctor – generates two distinct responses, depending on the social position occupied by Lispector: “Authoritarian in the first case, confused and subordinate in the second” (“Lispector, cronista,” p. 105).16

In addition to giving her the “childish and clear” expression of a person who was, still in Lispector’s terms, “partially awake” (Too Much of Life), Aninha’s “crazy sweetness” was, so to speak, contagious: “I, too, felt a kind of sweetness inside, which I can’t explain. Yes, I can. It was love for Aninha” (Too Much of Life); or even: “The apartment was filled with the kind of crazy sweetness that only the now vanished Aninha could leave behind” (Too Much of Life). But this is not the first time in her chronicles that the author highlights the “contagious” component of “sweetness:” “The sweetness is contagious: I grow still and sweet too,” writes Lispector in “Black Doe” (April 5, 1969; published in The Foreign Legion as “Africa”) when “surrounded by skinny, black, half-naked girls” (Too Much of Life), during her brief stay in Liberia. In this chronicle, Lispector describes a series of frustrated attempts to communicate with the residents of the “towns of Tallah, Kebbe and Sasstown, in Liberia” (Too Much of Life), where a sign of goodbye (“They love waving goodbye”) can be answered with “obscene gestures” (Too Much of Life), a very long sentence in which “I cannot hear a single r or s, just variations on the scale of l” (Too Much of Life) is summarized by the interpreter with a very brief “She likes you,” and even the English poorly assimilated by the natives sounded like “another local dialect” (Too Much of Life). For, to contrast with these lapses of language and gestures, or precisely at the moment when the author, feeling “awkward,” tries to show the use of her headscarf to an indifferent group of young black women, she becomes contaminated by the “sweetness,” whose only concrete manifestation consisted, as in the case of the “crazy and gentle” maid, in a certain expression on her face: “In their opaque faces, the painted stripes are looking at me. The sweetness is contagious [….]” (Too Much of Life). The state of sweetness is as mysterious as it is frequent in Lispector’s chronicles and fiction. This obviously does not concern the subaltern “sweetness” idealized by the employer class (synonymous with absolute devotion, as is the case in the mammy myth), although it is generally associated in Lispector’s work with those who are in a position of subalternity (animals, in “State of Grace—A Fragment” a peasant woman, in “Such Gentleness;” fools, in “On the Advantages of Being a Fool”). Sweetness, in this case, is the crucial (utopian?) state for the contact, literally the tact, between women of distinct sociocultural conditions, since it dispenses with the desire for “comprehension” and language: “One of them steps lightly forward, and as if partaking in a ritual—movement and gesture are everything to them—she very intently touches my hair, strokes it, feels it. They all watch. I don’t move, so as not to frighten them.” (Too Much of Life).

In the chronicle “God’s Sweetnesses,” Lispector likewise narrates her “ritual” of contact with a domestic servant: here, it had been necessary for the maid to have “appeared” in her gentle madness, or contagious sweetness, and no longer through the disturbing desire to read her mistress’ books. Nonetheless, for such a state of “sweetness,” or of “love,” Lispector’s reactions following the departure of her maid Aninha are somewhat “fierce:” “[S]he didn’t like ‘sugared water’ and she certainly wasn’t that,” writes the author, finally realizing a less ironic meaning, or effect, for such a cliché-expression. “Neither is the world, as I realized again that night when I sat up into the small hours, smoking fiercely. Oh, how fiercely I smoked! Sometimes I was filled with anger, then horror, then resignation” (Too Much of Life). According to Castillo, such reactions result from the experience of self-awareness, or revelation, in which the maid Aninha “serves as Lispector’s mirror, exposing the ugliness of her social preconceptions” (“Lispector, cronista,” p. 104).17 In my view, nevertheless, instead of a narcissistic attention focused on oneself, where the other acts only as a “mirror,” such “fierce” reactions reveal, on the contrary, a “troubled sense of maternal obligation” (“Fatos,” p. 109), which is more consistent with the author’s other social chronicles. In general, her encounters with the precarious reality of subjects who circulate in the immediate spaces of her chronicles are narrated as traumatic experiences of a renewed awareness of unresolved social wounds: “Neither is the world [‘sugared water’], as I realized again [….]” (Too Much of Life)

On the other hand, no matter how traumatic this view of precariousness is, Lispector likewise feels/expresses a compulsion to “social action,” which in some texts she defines as a duty to “take care of the world.” In the chronicle “I’m Taking Care of the World” (March 4, 1970), she writes:

Before I go to sleep and take care of the world in the form of my dreams, I make a point of checking that the night sky is full of stars and is navy blue, because there are nights when it appears to be navy blue not black [….] I observe the boy who must be about tem, terribly skinny and dressed in rags. A tubercular future awaits him, if it hasn’t already arrived [….] Is taking care of the world hard work? Yes. And I remember the terrifyingly inexpressive face of a woman I saw in the street. I take care of the thousands of people living in the favelas on the hillsides [….] You might well ask why I take care of the world: it’s because that’s the job I was given when I was born. And I’m responsible for everything that exists [….]. (Too Much of Life)

If “taking care of” means “checking” on or being “responsible for” something or someone, this expression can likewise be read as “caring for” and “protecting” the other whose capacity for agency is perceived as null or precarious. Lispector then feels called to respond maternally to the sight of the malnourished, tubercular boy, or to the difficult memory of an anonymous and “terrifyingly inexpressive” woman’s face. In other words, she adopts a “maternal thinking” (in Sara Ruddick’s terms)18 when she speaks of these anonymous, precarious subjects and “people living in the favelas on the hillsides” to justify her continuous and exhausting task of “taking care of the world” and of feeling “responsible for everything that exists.” I leave out of the discussion the impossibility of such an incumbency and, certainly, the maternalist implications of her role as “protector of the poor and animals,” to highlight the fact that such an attitude makes reference to the sui generis form of social commitment based on an “ethics of care.”19 On the other hand, as Marta Peixoto (2002) argues, Lispector’s “activity of taking care proves to be no more than a careful observation of the visual surfaces of the world and is thus completely self-enclosed, in no way affecting, for better or for worse, the objects of care, which include the dispossessed” (“Fatos,” p. 109). In the chronicle in question, Lispector tries to give the maid Aninha a better place in the world, where even her “ugliness” (“I forgot to mention that Aninha was very ugly”), or her “lack of taste” in dressing, “was another of her sweetnesses” (Too Much of Life). However, her maternal “activity” is limited to recording Aninha’s sweetness, even for an audience that, she knew very well, would forget her in a short time: “Dear God, who could possibly love her? The answer: dear God” (Too Much of Life).

IV

Acting in Lispector’s chronicles as a mediator between two socially opposed worlds and, on the other hand, as a sign of socio-racial otherness in the chronicler’s family universe, the domestic servant therefore acts on the self-constitution of the ethical subject in an ambivalent manner: she is the pretext for the chronicler’s traumatic but morally edifying incursions into peripheral urban areas, although she likewise acts in these chronicles as a source of guilt and embarrassment. Lispector recognizes her conflicts and the tensions inherent in the mistress-maid relationship, but she is unwilling to answer to the demand that the presentation of these conflicts produces. This is perhaps why such conflicts and tensions are manifested as a state of attention (versus a “social action”). On the other hand, despite her oscillations between “seeing” and “not seeing” (“Fatos,” p. 119) the conflicts generated by this affective-labor relationship of social exploitation, the chronicler proposes something original in the history of Brazilian literature. In the first place, she introduces the class trauma and guilt triggered by the encounter with poverty. As Jean Franco (2002) argues, “[a]lthough apparently motivated by the modernist desire to represent and control dangerous material [in the form of cultural fields], Lispector’s encounter with the low is invariably shattering” (Franco, “Seduction of Margins,” p. 204). Furthermore, from the social disencounters in her domestic family universe, Lispector extracts an aspect – the maid’s imaginary gaze at her mistress, or her “censored resentment” – that for obvious reasons challenges the mythologized appropriation of the domestic servant as a symbol of interracial fraternization (the mammy, the seductive mulatto).

Such reflections unfold in her 1970s narrative in a series of questions about the power of the intellectual, and of literature, to intervene in the state of things in the world. Certainly, her inquiries are somehow integrated into the “culture of defeat” (FRANCO, 2002), a characteristic of the post-utopian, or post-revolutionary, Brazilian literature of those years; in the terms of Renato Franco, a literature forced to “narrate the impasses of the writer who could not decide if it was more necessary to write or to become involved politically, thus constituting a type of novel that was disillusioned both with the possibilities for society’s revolutionary transformation and with his or her own condition” (“Literatura e catástrofe” [Literature and Catastrophe], p. 358).20 In her own way, Lispector would arrive at similar impasses in those years. For example, in The Hour of the Star (1977), the narrator is willing to tell “the lame adventures” of the northeastern migrant woman Macabéa, although he does not expect to overcome, through literary mediation, the social distance between himself and his character: “This book is a silence. This book is a question.”

The various testimonies of domestic servants that emerged from the 1980s onwards in Brazil are a sign that, for one reason or another, the “silence” or the “question” did not meet the new political pressures imposed by the emergence of popular social movements. Nor did the “silence” serve as a response for the emerging domestic servant authors who saw their cultural practices as an unprecedented exercise in citizenship. Therefore, despite confronting the contradictions between her positionality as a mistress and her opposition to the culture of domestic servitude, Lispector is generally close to other canonical Brazilian writers. Her chronicles about domestic servants seem to be more at the service of building her public image than of the interpretative struggle to revise the stereotypes that have been producing stigma and injustice against domestic workers in modern Brazilian society.

- This essay was originally written for the book O cuidado em cena: Desafios políticos, teóricos e práticos, 2018, edited by UDESC, from Florianópolis. We are grateful to Marlene Tamanini and Francisco Gabriel Heidemann for granting us permission to republish it.[↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quotes in Portuguese read: “comenta[r] a forma como vivemos, os costumes e valores morais no contrato social das grandes cidades;” “gênero de escritor;” “sobressair-[se] no registro do cotidiano em toda a sua urgência, na sensibilidade à fascinante diversidade da vida, na construção de cenas completas em vez de, secamente, recontar as notícias.”[↩]

- It is worth highlighting the fact that her sense of social responsibility and condescending attitude as a “protector of animals” ends up reinforcing a certain maternalist ideology, which, according to Judith Rollins, tends to define the relationships between employers and their domestic servants.[↩]

- The maid as a sign of mediation between opposing worlds (house/street; living room/back of the house; etc.) appears frequently in literature, above all in childhood memoirs. See Leonore Davidoff’s study on the domestic servant in children’s memoirs of the British Victorian period, “Class and Gender in Victorian England” (In: Worlds Between: Historical Perspectives on Gender and Class. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995); also see the analysis of the domestic servant in the shaping of the child Walter Benjamin’s desire in Peter Stallybrass & Allon White, “Below Stairs: the maid and the family romance” (In: The Politics and Poetics of Transgression. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986). In Lispector, one of the most interesting examples of the domestic servant in her role as mediator between the bourgeois universe and that of poverty appears in a passage, still unpublished, from her manuscript “Objeto gritante” [Screaming Object] (on the passage in question, see my essay “Nunca fomos tão engajadas: Style and Political Engagement in Contemporary Brazilian Women’s Fiction.” In: Anne J. Cruz et al. (ed.). Disciplines on the Line: Feminist Research on Spanish, Latin American, and U.S. Latina Women. Newark, DE: Juan de la Cuesta Press, 2003).[↩]

- Her little-known production as a columnist on issues “for women” in some Rio de Janeiro newspapers was partially published after the exhaustive work of Aparecida Maria Nunes, who selected and edited her women’s chronicles in three collections: Correio feminino (2006), Só para mulheres: conselho, receitas e segredos (2002), and Clarice na cabeceira: jornalismo (2012) – all published by the Rocco publishing house.[↩]

- Her reference to domestic slavery constitutes one of the rare passages in her chronicles in which race is treated as a relevant factor in the structuring of relationships between mistresses and maids.[↩]

- As Vilma Arêas reveals in “Peças avulsas” [Individual Pieces], the view of the “ódio censurado” [censored hatred] of domestic servants appears in her literature based on the personal reading of a newspaper article, “Un ‘prolétariat’ en Tablier Blanc,” written by Elvire de Brissac and published in Le Monde on March 14, 1963. According to the article in question, the “condições psicológicas” [psychological conditions] of this social group, or the feelings that constitute their relationship with their mistresses, are precisely repressed resentment, humiliation, and alienation.[↩]

- LISPECTOR, Clarice. “Objeto gritante.” Clarice Lispector Archive. In: Archive-Museum of Brazilian Literature at the Rui Barbosa House Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, 1971. [Translator’s note: the original quotes in Portuguese read: “sertaneja;” “É capaz de sentir-se mal. Porque o mar não é compreensível. É sentido e é visto. Estou me pondo na pele desta empregada que se chama Severina. E eu sendo ela fico toda assustada. Devo ter visto uma primeira vez o mar. Só que não me lembro…”] [↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “Mandarei embora Severina: ela é oca demais. Não tive coragem de ir levá-la a ver o mar: temia sentir por ela o que ela não sentisse. É nordestina e é oca de tanto sofrimento.”] [↩]

- As the author explains in this chronicle, it concerns an immigrant maid from Italy during her years in Berne, Switzerland.[↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “um certo clima de teatro do absurdo.”[↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quotes in Portuguese read: “sutilezas;” “certas finuras de reações psicológicas;” “bastante fatalizado a ter empregadas um pouco, como se diz, sôbre a débil mental;” “a falar frequentemente coisas que lembram as personagens;” “imita[r]-lhe a arte.”[↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quotes in Portuguese read: “Quero empregada toda viva embora me dê mais trabalho;” “Não posso ter coisa morta em casa.”] [↩]

- Lispector would once again mention the use by a domestic servant of erudite, sophisticated words, that is, words “proper” to the employer class, to narrate a situation of social “enigma.” In the chronicle in question, “Enigma” (April 26, 1969), she accidentally meets a woman in the elevator of her building who “spoke like the mistress of the house, her face was that of the mistress of the house,” (Too Much of Life), but who had entered “her” apartment “by the service entrance” and, moreover, “was wearing a uniform.” Nevertheless, since it concerned someone else’s maid, this shaking of social boundaries does not “embarrass” her; the final mood of this chronicle appears more out of obedience to its generic “conventions” than out of a need on the part of the author: “‘And—I swear—she added this: ‘Life has to have a sting in the tail, otherwise you’re not really living.’ And she used that expression ‘a sting in the tail,’ which I really like” (Too Much of Life).[↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “pressupostos de classe e sexo.”] [↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “autoritária no primeiro caso, confusa e subordinada no segundo.”] [↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “serve de espelho para Lispector, expondo a feiura de seu preconceito social.”] [↩]

- RUDDICK, Sara. Maternal Thinking: Toward a Politics of Peace. 2nd ed. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.[↩]

- Despite the controversies surrounding her proposal to dissociate the “work” of maternity from the figure of the biological mother, in addition to a somewhat bourgeois view of this maternal work, Sara Ruddick’s book, Maternal Thinking (1st edition, 1989) inaugurated an important debate on the ethical implications of maternal care. According to Peta Bowden, in Caring: Gender-Sensitive Ethics (New York, London: Routledge, 1997), “Ruddick attempts ‘to identify some of the specific metaphysical attitudes, cognitive capacities, and conceptions of virtue [….] that are called forth by the demands of children [adopted, biological, or raised]’ (MT, p. 61), with the aim of ‘honouring’ ideals of reason that are shaped by responsibility and love rather than by emotional detachment, objectivity and impersonality. Her claim is that the practices arising from mothers’ responses to ‘the promise of birth’ have the potential to generate and sustain a set of priorities, attitudes, virtues and beliefs that inform an ethics of care and a politics of peace” (Bowden, Caring, p. 24–5).[↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quotes in Portuguese read: “cultura da derrota;” “narrar os impasses do escritor que não sabia decidir se era mais necessário escrever ou fazer política, constituindo assim um tipo de romance desiludido tanto com as possibilidades de transformação revolucionária da sociedade como com sua própria condição.”] [↩]