, Ulysses, A Little Neurotic. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2017. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2017/09/06/ulisses-um-pouco-neurotico/. Acesso em: 26 July 2024.

Ulysses is not only the great mythical character who with a cunning idea ended the bloody, ten-year Trojan War, moving both men and gods. In presenting the Trojans with a wooden horse full of Greek soldiers, Ulysses, or Odysseus in the Greek reference, could then return home.

This return is one of the most beautiful works of literature and is recorded in the Odyssey. From here on, a whole legion of Ulysses (real and symbolic) are inaugurated in the literary realm. Starting with the obvious: the title of the novel by James Joyce – Irish author with whom Lispector has been compared many times. Ulysses narrates a short interval in the life of agent Leopold Bloom, in a kind of condensed Odyssey.

Yet another Ulysses is present in An Apprenticeship Or the Book of Delights. The novel turns this character into a professor of philosophy, Dori’s guide in the apprenticeship of pleasure and loving/sexual autonomy.

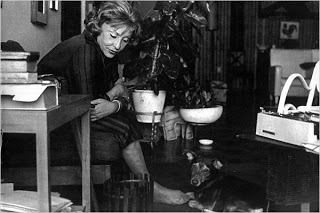

Even more prosaic, albeit literary, Ulysses was Clarice Lispector’s last dog, a mutt who stole cigarette butts and lined up for Coca-Cola and whiskey for visitors. He was so eccentric – “and a little neurotic, as it turns out” – that he earned a robust note in the infamous periodical O Pasquim.

The animal, which also went by the names of Vicissitude, Pitulcha, and Pornósio, was bought when the author’s two sons, Pedro and Paulo, had grown up and moved on. She “needed to love a living creature who gave me company.”

If for a dog, “being with the owner means being with God,” it is not much different for some owners. Indeed, it is difficult to write about this category, animals, without falling into sappiness. Among a few authors, I highlight a stanza from Mayakovsky that is as poignant as it is affectionate:

I love the creatures.

When I spot a pup–

There’s a funny one–

all bald–

hangs round the baker’s—

I feel like I could cough my own liver up:

Here, doggie

don’t be so shy, dear, take this!

In A Breath of Life, published a year after Lispector’s death, the narrator speaks extensively about Ulysses, the dog.

“I can speak a language that only my dog, the esteemed Ulysses, my dear sir, understands. Like this: dacoleba, tutiban, ziticoba, letuban. Joju leba, leba jan? Tutiban leba, lebajan. Atuoquina, zefiram. Jetobabe? Jetoban. That means something that not even the emperor of China would understand.” And furthermore: “My dog Ulysses and I are mutts. Ah what a good rain is falling. It’s manna from heaven and only Ulysses and I know it. Ulysses drinks ice-cold beer so adorably. One of these days it’s going to happen: my dog is going to open his mouth and speak. It will be glory.”

Lispector solves the issue of the non-language of the animal in a no less creative way. If the dog were to be a state without language – “How envious I am of you, Ulysses, because you only are” –, in the children’s book Quase de verdade [published as “Almost True” in the collection The Woman Who Killed the Fish], Ulysses himself is the narrator of the story involving silly chickens and a proud fig tree.

A recently inaugurated bronze statue of Lispector is located in the Leme neighborhood, where she lived for more than a decade. Today the statue attracts hundreds of visitors, provoking the envy of the nearby statue of Drummond, further ahead along the Copacabana boardwalk. Beside the placid figure of the author, Ulysses is immortalized.

Perhaps if Ulysses could talk – or better, if he could read poetry–, he would recite for his owner the verses of Mayakovsky in the human version.

*Elizama Almeidais a PhD candidate in Materialities of Literature/University of Coimbra, lacuna‘s study group researcher and cultural assistant at Instituto Moreira Salles.