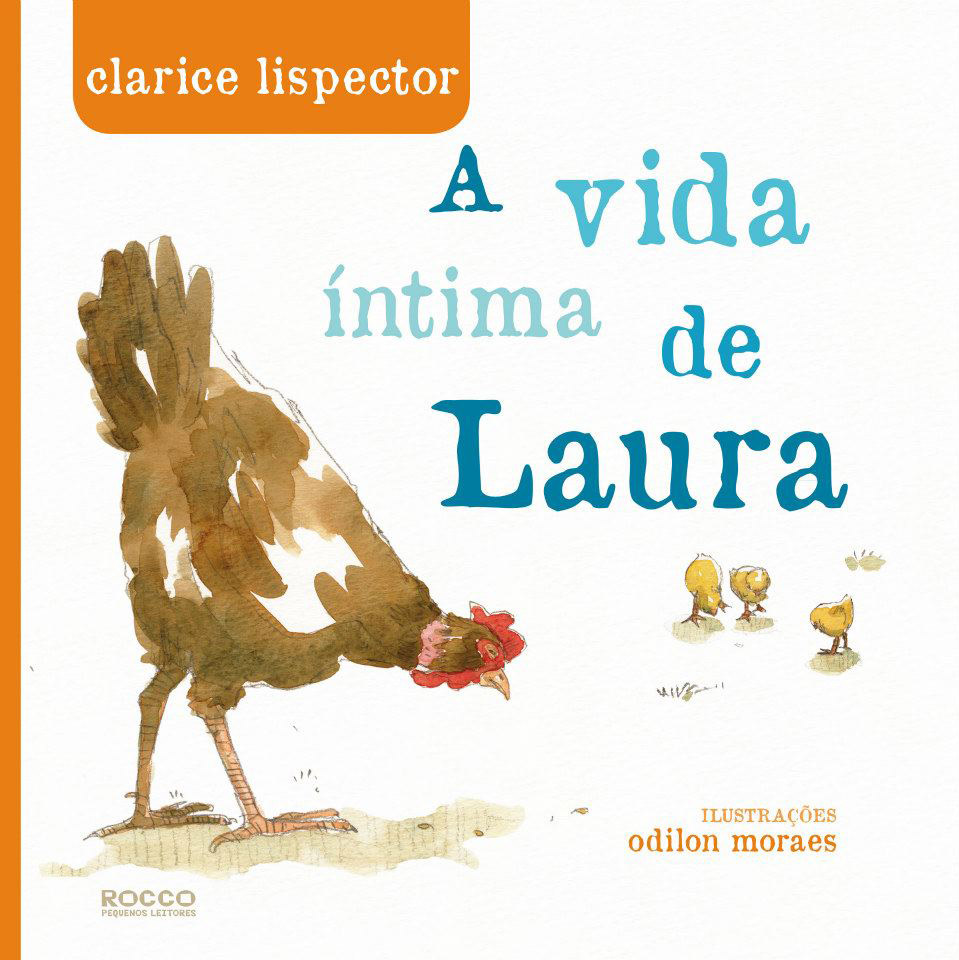

Clarice Lispector’s literary production addressed to children is marked by non-didacticism, working with language and unusual narrative perspectives. In Laura’s Intimate Life (1974), Clarice’s third published work for children, from the beginning a productive dialogue is established between narrator and reader, based on procedures that border upon intimacy and cut through the reading/understanding of the story. Already in the opening the narrator (in fact, Clarice Lispector herself) prompts us to the possibility of revealing secrets and unveiling domestic confidentialities and mysterious essences. At the same time, she emphasizes the affective connection with the reader, through intimate approaches (“Dou-lhe um beijo na testa se adivinhar.” [I’ll give you a kiss if you guess], “Peço a você o favor de gostar logo de Laura…” (I ask you lease to like Laura right away]). Laura, the protagonist, is a hen, presented without any aura of idealization: “Laura tem o pescoço mais feio que já vi no mundo” [Laura has the ugliest neck I’ve ever seen in the world], “Laura é bastante burra” [Laura is really stupid], “nunca vi ninguém mais sem jeito que essa galinha” [I’ve never seen anyone as awkward as this chicken]. A domestic critter—common, far from heroism, and dear to the children—stars in the plot, recalling other chickens, as well as eggs, that are constants in Clarice Lispector’s fiction as motives for reflection on the human condition. The plot is made up of short episodes, which link the birth of Hermany, son of Laura and Luis, her husband; the attempted robbery of Laura by a chicken thief; the near death of the protagonist; and, finally, her encounter with Xext, inhabitant of Jupiter, who asks Laura how “eram os humanos por dentro” [they were human on the inside]. It should be noted that Laura is afraid of death, a theme that is almost forbidden in children’s literature, and that is here treated directly in the narrative. However, once again in the author’s set of works for children, instead of facts, what matters is the description and reflection proposed by the narrator. In this disordered narrative, the continuously playful tone makes the connection between the narrator and the reader even closer. It does not make use of artifices that diminish the child reader, reducing her ability to think, but rather activates the possibility of exploring elements that are commonly overlooked in daily life and drawing observations from them. Laura’s adventures are built on linguistic explorations, meaningful clues, and life revelations. And, in this adventure, at every moment the reader is accompanied by the narrator, who stresses the concern with intimacies, with the “humanos por dentro” [humans on the inside], starting with Laura’s fixation.

ByRosa Gens