IMS, Equipe. Scliar in Cabo Frio. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2021. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2021/08/11/scliar-in-cabo-frio/. Acesso em: 27 July 2024.

I spent an unforgettable weekend in Cabo Frio, hosted by Scliar who painted two portraits of me. Scliar’s house is very beautiful.

Cabo Frio inspires Scliar. I asked him about so much creativity. Answer:

— I think that living is a creative act. I try to do everything that I like and try to discover everything that disturbs me. I believe that in Cabo Frio it is possible for me to concentrate, which allows me to discover the thread. Then I just need to work on it. I do not understand living without working. The thing that I find most important in anyone’s life is to discover what he or she would like to work on.

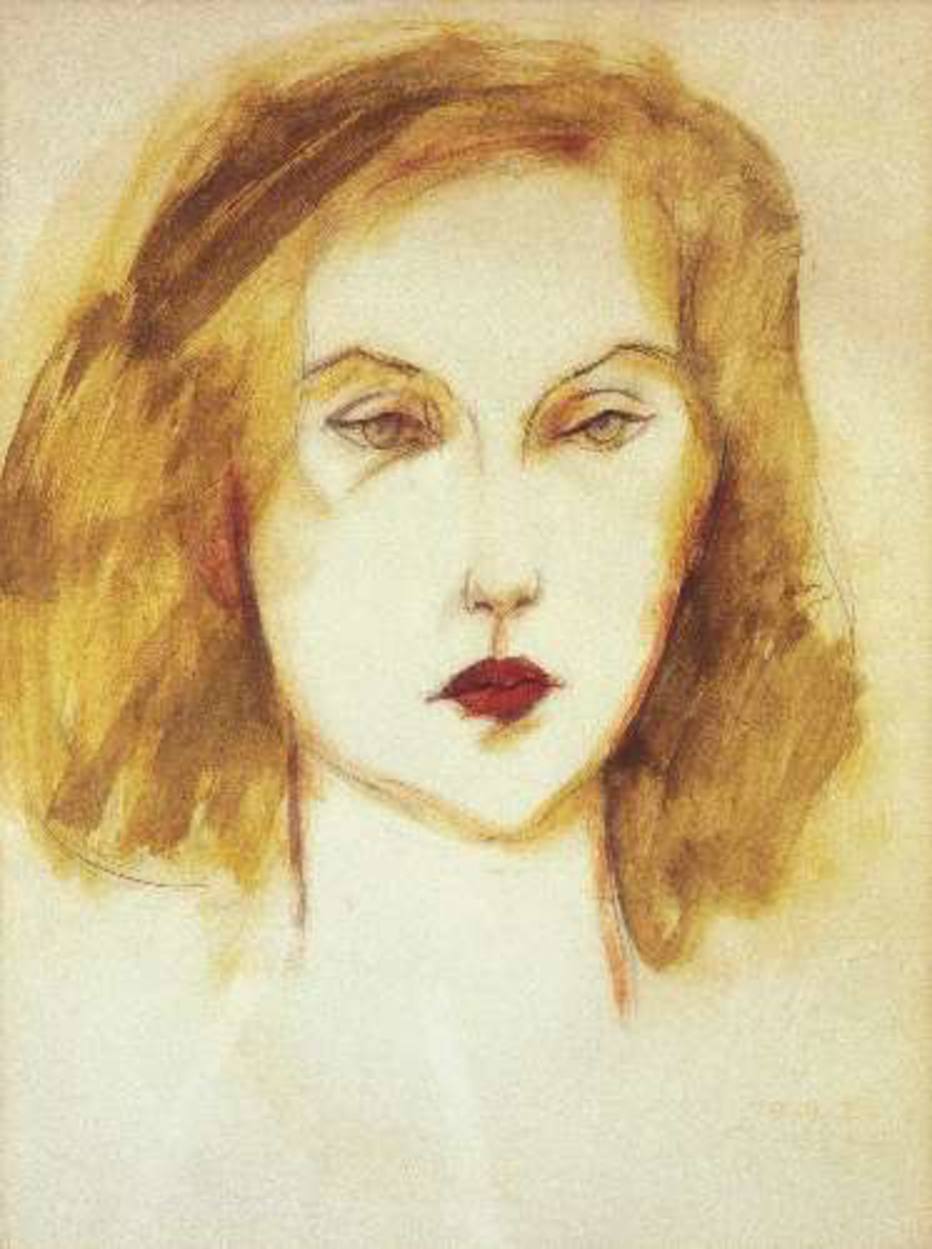

Scliar has three dogs and I played lovingly with them. Everyone in Cabo Frio knows Scliar’s house. I verified this when early in the morning I went to buy the Jornal do Brasil, since I cannot start my day without reading this newspaper. But I got lost because I have poor sense of direction. As I got lost again, I asked for directions — and everyone knew where Sciar lived. I visited José do Dome who gave me a beautiful painting and brought me wild cherries. Before painting, Scliar made many drawings of my face. I told him about when I posed for De Chirico. He said that it is apparently easy to paint me: just put protruding cheeks, slightly slanted eyes, and full lips: I am caricaturable. But my expression is difficult to capture. Scliar retorted: every painting is difficult.

— When did you start painting?

— I have been drawing and painting since always. Cabo Frio in the winter is calm and allows me hours of voluntary solitude. That is when I work. An apparently intuitive or apparently rational process ensues. The two things are contradictory, but they exist and are intertwined. I make use of the time to get down to work, while I leisurely listen to music and read.

Suddenly the telephone rang and Scliar went to answer it. And as incredible as it may seem, the phone call was coming from Barcelona, Spain, and was from Farnese with whom Scliar spoke for a long time.

— What do you feel when you paint? Do you feel restless like me when I write a book?

— I am not sure, because the process is so different for every painting. Oftentimes the painting – although the drawing is already structured – the painting seems strange to me until it is unleashed. And that begins with the discovery of certain relationships among the colors, with a plane in a definite tone that guides the proposition in a direction that is different from what was initially proposed. Other times it is a gesture that sets a value, a vibration that is unforeseen. Or an observation from looking through a window that brings me the color of a boat passing by. What do I know? It is all valuable and the result is what counts.

I almost forgot João Henrique who has green color and who gave me the night-blooming jessamine to perfume my nights. He is wonderful and sells very well. I have always liked men more and was happy to have two male children. João Henrique is a real man. If he were not such a man. José do Dome likes yellow very much.

There are also Dalila and Mercedes who cook very well. Mercedes has been with Scliar for twelve years and he calls her mom. Dalila makes a spaghetti with heart of palm that is amazing. Mercedes’ hair is completely white and she kisses Scliar.

— You like still lifes, I know that because I’ve seen really fantastic ones.

— As much as anything else I paint. Maybe they grant me greater freedom in the organization and later destruction of these processions that I have seen and modifying even their framework in a way that surprises me. That is when the work really begins.

— Talk about the silence in your house and how it affects you.

— I think that my silence is being surrounded by all of the sounds that I like and that allow the atmosphere that I seek for my work. I think that life is so rich and unexpected that every instant I need to be open to what surrounds me so that I do not miss anything, if possible. Can you hear the sound coming from the kitchen or from the guy who moved the broken glass up there? They are vivid signs that prove we are also the silence. I think that this is important for my work, that I try to reflect in a permanent reflection and integration with everything that happens and comes to me. I think that life is a simple thing. But it is difficult to transmit it. When we like people and work on their behalf we establish a relation that we do not always immediately realize is essential.

As for the mutating forms, speaking of them, Scliar said:

— It is my work continuing. In the end, what do we seek in each work if not the possibility that it will permanently renew itself? Of course, this happens in each new person who observes and discovers it. Fortunate is the work that renews itself constantly for the same person. Every work should contain this possibility of a permanent unfolding. My instants are sets of three or four paintings, each with its own balance, capable of restructuring itself in communion with the others. Since each painting contains its own propositions, I multiply these discoveries in each mutation proposed. You see, it is the same initial problem amplified.

— Do you work every day?

— Yes, even when I am not working.

* Translated from the Portuguese by Marco Alexandre de Oliveira and edited by Sean McIntyre.

**A chronicle published on October 28, 1972 in the Jornal do Brasil and never collected in book form, not even in The Discovery of the World, or in the recent Todas as crônicas (All the Chronicles).

*** The image that illustrates the text is the portrait of Clarice Lispector made by Carlos Scliar which the chronicle mentions, and which is the reason for the writer’s visit to the studio of her painter friend, in Cabo Frio.

**** The chronicle “Scliar in Cabo Frio” presents an unorthodox punctuation, especially with respect to the use (or not) of commas. During the period in which Clarice Lispector contributed to the Jornal do Brasil, from 1967 to 1973, her editor Marina Colasanti lets us know in the preface to Todas as crônicas (All the Chronicles) that one of “her constant requests was that we recommend to the proofreaders not to touch her commas.” For, as Clarice puts it in the chronicle “Minha secretária” (My Secretary): “my punctuation is my breath within the sentence.” Thus, strictly following the author’s warning, in the edition of the text now published, we opted not to disturb the commas – despite having observed that they sometimes seemed to have been intentional, that is, following the writer’s breath, but other times not, who knows an inattention common to texts written quickly to meet the newspaper deadline.