Hack, Lilian. Meaning is a Breath: Images in Clarice Lispector. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2021. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2021/04/14/meaning-is-a-breath-images-in-clarice-lispector/. Acesso em: 01 March 2026.

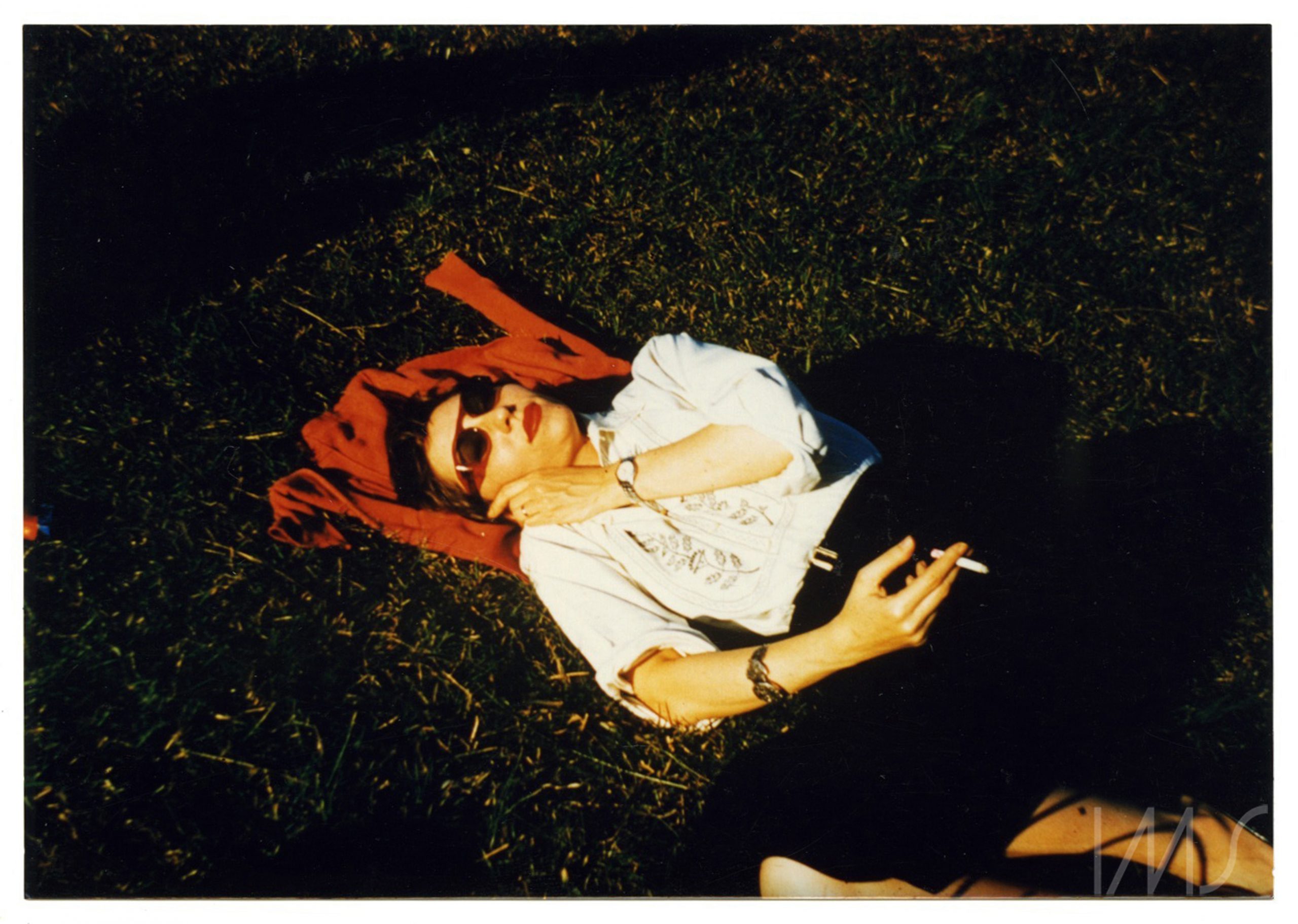

Crossing the Atlantic Forest breathing outside, I enter the small research room with white walls and lots of tables1. The interior resembles a kind of aquarium, with a large glass extending from one side to the other of the wall, in front of the hallway that gives access from the elevator to the other rooms on the same floor. The air conditioning feeds the environment and takes care of its noises. Preparing an atmosphere for reading and writing, I see an empty table next to a chair, in which I sit. My hands, covered by surgical rubber gloves, still do not know exactly how to measure touch. In this setting, I wait for the two paintings by Clarice Lispector that are under the care of the Literature Archive of the Moreira Salles Institute (IMS)2. After a few minutes, not knowing what to do with my eyes, I accompany the footsteps of a woman who brings two boxes in her hands, smiling discretely out of restlessness. As she opens the door to the glass room, she receives the help of her colleague, who was supervising my wandering eyes and the concentration of another researcher. I feel a certain complicity between the two as they put the volumes on a higher table, right behind the one where I had sat down. Promptly, and with the discretion of a few words, I join them. And then, in a whisper, I hear something more or less like this: “Wow, I’ve never seen these paintings before….” Escaping the tension, the woman from the boxes lets out a smile and adds: “Me neither!” I was absolutely stunned by what I heard, equally thrilled by my first time. So we opened the boxes together and saw the two paintings with the same surprise, in a brief and intense moment.

That was the first sensation which I had when I saw Clarice’s paintings: my whole body shivered in a flush that was shared with these two women who worked every day at the archive. A kind of slip, a discomposure, a “human dismantling.” As Clarice wrote, “She needs to move her whole boneless head to look at an object.”3 – it is necessary to disorganize the act of seeing in order to see a disorganized form. My flush understood this measure of sharing an unveiled intimacy that fluctuated from strangeness to bodily rapture. Two images were lit up in an intense red inside the boxes and offered themselves for the first time to the gaze of three women. The painting was like a body shown inside out: beyond the entrails, there was the uterus. Clarice’s painting had the viscosity of a placenta. Her images had the consistency of a thing.

Gradually, I contained my emotion and identified my sensations. Each of us resumed our places, and I dedicated myself to the details. These images have the consistency of trees, of vegetable matter, wood being the support for these two paintings. In one of them, the vertical lines visibly follow the designs provided by the wood, and create a spatiality that is flaccid and hard at the same time. The warm colors loosen in a lassitude given by the repetition of the strokes. It is the painting titled Interior de gruta (Cave Interior), as can be read on the back which contains this inscription next to Clarice’s signature. However, its dating is controversial, for it is hidden in a dense mass of paint. Only in the transparency of the colors do we guess with a certain insistence the year 1960, drawn with a felt-tip pen in a small “text box,” which was demarcated by Clarice with the paint itself, on the lower right side of the painting’s surface. This date is the same as that recorded in the writer’s collection at the IMS.

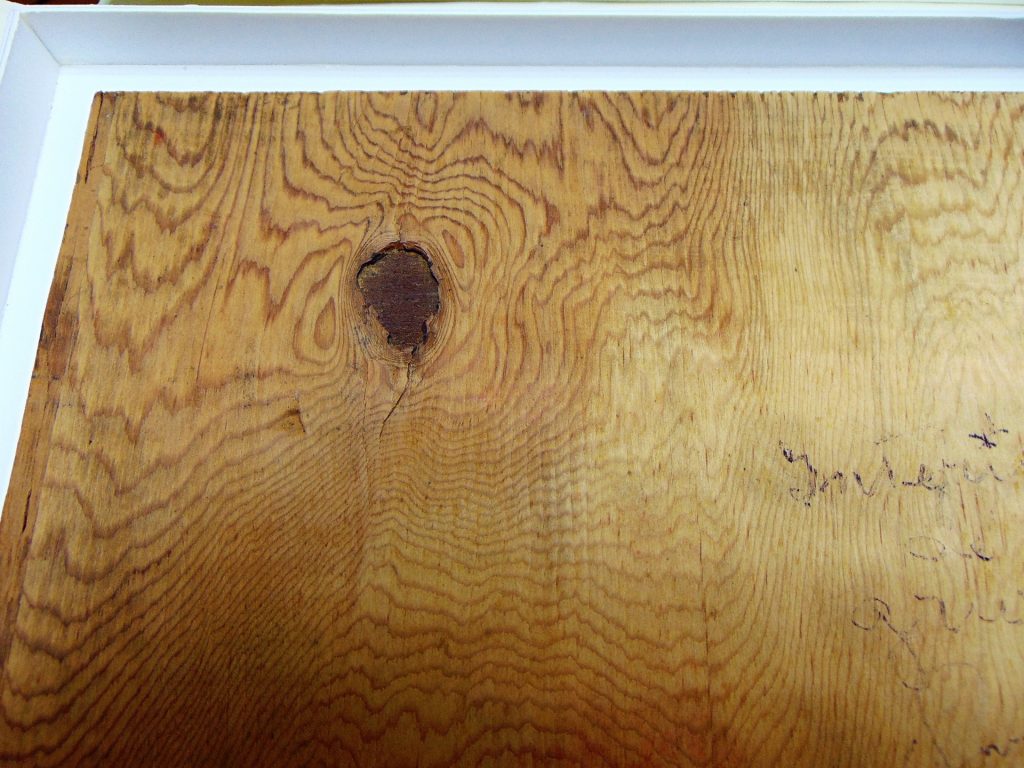

The other painting on the table is recorded, in the same collection, without a title or a date. In this painting of wild and quick brushstrokes, the green color predominates next to the very pasty blue, white, and red strokes and smears, in a gesture very different from the one we sensed in the previous painting. When I request to see it outside the box to which it was attached, I notice how Clarice gave it special care, framing the small painting made on the thin wooden board and adding a hook on the back – we can even see the seal of the framer who did the work. But it will only be on a second visit to the archive, this time in another consultation room and with natural lighting, that it will be possible to see an inscription that seems to draw the title, the date, and the signature on the painting. Insisting with a magnifying glass at the edges of the frame, it is possible to see lines that, in this consultation, allowed me to suppose the inscription of the word “Mata” (Forest) and the year 1975 next to Clarice’s signature, again in the lower right corner, in the small “text box,” where it proceeds in the same way, covering the record with ink.

Since research always holds surprises and discoveries generated by the archive’s own inexhaustible status, it was only very recently, months after this consultation and the publication of the doctoral dissertation in which I make this attribution, that a new investigation with equipment more fit for the task, revealed that the title of this painting would be Esperança (Hope), dating from May 1975.

It is curious that the reading and confirmation of the title depend on a certain insistence, leaving us extremely uncertain. This occurs in other paintings by Clarice. Had she acted in order to erase the traces, to elide names and titles? As researchers, we are immersed in the task of unveiling and disseminating, but as artists, we know full well that incompleteness, chance, and hesitation are decisive factors in the outcome of a work. My hands in surgical gloves are ultimately tiny in the face of the unprecedented experience of contact with the work. What remains of the traces is always subject to recreations, and that is what nourishes the words.

In comparison, we clearly see how these two paintings are different from each other. Interior de gruta (Cave Interior), from 1960, has an economy of gestures. The watery paint was well spread and absorbed by the wood, which consists of a surface so thin and improvised that it has not escaped the deformations of time. There is a transparent, viscous layer covering the painting, which may be a dull varnish or a colorless gum. The vertical lines follow the designs of the wood, and in fact recall the walls of a cave, the walls of the cave. A few beings float through the painting and help to compose this shapeless landscape. They are small butterflies drawn with ballpoint and felt-tip pens, in cliché forms, that preserve a gesture of lightness, as if they were flying at the entrance to the cave. But the composition of colors, the freedom in making apparent the spots of paint that follow the lines of the wood, make the title induce this analysis, since the representational, mimetic meaning is not evident. It seems that Clarice paints a cave seen from the wood in its veins. The cave arises from the painting, not from a scene painted on it. Esperança (Hope), on the other hand, admitting this recently attributed title and dating, would have been painted more than ten years after Interior de gruta (Cave Interior). In this painting, there is a freedom and lightness in gesture that imprints the colors onto the picture. Applied with greater speed, the brushstrokes are dense from the paint mass, displaying more confidence in the command of the material and the technique. It is surprising to see how Clarice seems to be more at ease, without feeling so attached to this kind of boundary given by the lines of the wood. In addition, the frame demonstrates the genuine desire to exhibit this painting. Due to its more planned finishing, it stands out in relation to Interior de gruta (Cave Interior), as well as in relation to the other paintings by Clarice found under the care of the Museum Archive of Brazilian Literature (AMLB) at the Rui Barbosa House Foundation (FCRB), which has most of the collection of the writer’s paintings, with sixteen paintings, all made during the same year of 1975. However, Interior de gruta (Cave Interior) marks the presence of a theme that seems to be very important for the writer, since she will repeat this motif in another painting titled Gruta (Cave) – which is found under the care of the AMLB/FCRB.

This presence of the caves is also intense in the books in which Clarice left us records of aspects of her paintings. In Água Viva4, the elusive painter character who ventures to write for the first time offers us the following passage:

I want to put into words but without description the existence of the cave that some time ago I painted – and I don’t know how. Only by repeating its sweet horror, cavern of terror and wonders, place of afflicted souls, winter and hell, unpredictable substratum of an evil that is inside an earth that is not fertile. I call the cave by its name and it begins to live with its miasma. I then fear myself who knows how to paint the horror, I, creature of echoing caverns that I am, and I suffocate because I am word and also its echo.

We can suppose that it concerns the painting Interior de Gruta, which would date from 1960, and that therefore Clarice will already have painted in 1973, when she publishes Água Viva. In A Breath of Life5, it is the character Ângela Pralini who reveals to us the method used by Clarice to paint:

I am so upset that I never perfected what I invented in painting. Or at least I’ve never heard of this way of painting: it consists of taking a wooden canvas — Scotch pine is best — and paying attention to its veins. Suddenly, then a wave of creativity comes out of the subconscious and you go along with the veins following them a bit — but maintaining your liberty. I once did a painting that turned out like this: a robust horse with a long and extensive blond mane amidst the stalactites of a grotto. It’s a generic way of painting. And, moreover, you don’t need to know how to paint: anybody, as long as you’re not too inhibited, can follow this technique of freedom. And all mortals have a subconscious.

We have many indications that Clarice is referring here to the painting Gruta. And analyzing the two paintings on the same theme, we confirm that this is Clarice’s procedure for painting these and other pictures. That is how we could read these two novels from the records and traces that both keep of her paintings. And that is how Clarice reinforces, in her texts, this interest in caves in the elaboration of her images.

Clarice Lispector’s painting is at the same time close and far from her words. This means that we cannot so easily submit one to the other, that is, search in the literature for a meaning for her images, or believe that her images contain a meaning for her literature. We refer here to meaning experienced as correspondence, explanation, narrated fact, biographical or iconographic data to be unveiled. In her work, Clarice seems to ceaselessly escape from everything that makes sense, to escape from facts in the direction of sensations, of that which affects the body in a certain chaos of senses. Or rather, for Clarice, meaning is a breath. To friend and secretary Olga Borelli6 she would have once said: “My books, fortunately for me, are not overcrowded with facts, but rather with the repercussion of facts on individuals.”7 If this “repercussion of facts” – the surrender to sensation – is what moves Clarice’s writing, we can assume that it will be no different in her painting.

This is how we can see her images painted from this “repercussion of facts” on our body. But these “facts” are of a different order. We would say that Clarice’s painting is “overcrowded with material facts.” And these material facts produce sensations, as Gilles Deleuze8 very well demonstrated. The material facts of painting are different from historical, literary, narrative facts. At the level of sensation, they become detached from words, or move towards an indiscernibility between word and image. And at this point, the material facts of Clarice’s painting demands from us a perspective from the sensation that the image reflects on us. In other words, Clarice’s painting is made of the material of things. The painting is a thing. It is not an image of a thing, but this thing that is the image. It is necessary to repeat: the image is not in the place of things, representing them, but is something showing itself through the painting, the drawing, the colors, a gesture. As Maurice Blanchot9 wrote, “one lives an event as an image.” Sensation flutters before images, producing effects that are always different each time. It makes meaning escape, at the same time that it generates meanings. So that when we name the sensation, we fabricate possible meanings for the vertigo in which the image has cast us.

Georges Didi-Huberman10 shows us how much the history of art remains, at times, excessively concerned with the facts and ends up not worrying about the effects of painting, that is, with its repercussion on individuals. A proposition parallel to that of Clarice! According to the philosopher and historian, the image calls for a methodology of the gaze which would be that of metamorphosis: a desire for words to be transformed into an image, a desire for the image to be transformed into words, a desire to see the two as two sides of the same coin. And so, to write in the face of the image would be to desire for the metamorphosis to happen, for the word to make the image appear – as if in a flutter of wings.

Clarice writes and paints glued to sensations, to the repercussions of facts, glued to this desire for metamorphosis, wanting the material of things – of words and images – to deliver her a vitality that life lacks, for it pulsates in what is most tenuous and delicate, in an extraordinary infra-dimension of what is most ordinary. That is why she wants to escape the description of the painting, the description of the cave. It is suffocating to echo words. She thus surrenders to sensation, to horror, as we read in the passage quoted from Água Viva. Therefore, it will be necessary to make words an experience of exploring images, an exploration of the interior of the painted cave. It will be necessary to strip her human body and become an animal. It will be necessary to strip the writer to become a painter and vice versa. It will be necessary to strip words of their ready-made meanings to make them images. To metamorphose the body and words. To surrender to becoming. To return words to the gush of a spring, of a fountain that bubbles in the depths of the earth – living water. To return words to the meaning that comes as a breath. And on this point Clarice is a painter who has a singular capacity to understand that her images do not encounter a description, a double, an explanation in her words. The word touches the image precisely in that dimension in which it is delivered to the event, to the experience, to a fact lived and only very precariously transposed into words. To refer to this experience will be possible only by making words into images, and images are made of sensations, as Clarice herself has written.

It is not by chance that in the two novels in which Clarice explores her painting – Água Viva and A Breath of Life – the act of writing itself is a central theme, which makes writing function, and the writer is also a character in the plot, always in the process of being confused with the narrator, and sometimes even with the objects and scenes that are narrated. There is a tension, a suspension in the separation between subject and object, which we could transpose into a suspension of the separation between word and image. It is not by chance, either, that painting, the image, is what makes writing enter the vertigo of the impossibility of naming, a theme that is dear to a certain mystical-religious tradition, especially the Jewish one, which was certainly not foreign to the writer. But it is also a fundamental theme for any debate about the practices that involve writing about art, writing about the image, a clash faced by anyone who creates images or who elaborates discourses about them, and is confronted with transposing this process of creation/perception in words. And we know full well that all perception is a creation, and that writing would resume an infinite pulsation of images. These novels by Clarice expose the desperate attempt to offer a word that can reach the images in her sight, in the act of seeing – of seeing even her own paintings – encompassing a certain experience of seeing much more than naming the seen. Some of the titles of her paintings can be read in this way, as the attempt to enunciate an experienced sensation – to name the sensation and not the painting. Thus, Esperança (Hope), for example, will not be the representation of what Clarice believes to be hope, but the sensation that the painting causes to emerge in the face of the impulse to produce meanings. It does not concern only a game between visual perception and verbal description, of making words say the painting, say the seen, but giving words a capacity to see the sensation, to make words seers. It is not an echo, but a pulsation. A breath.

In November 1950, Clarice Lispector visits a prehistoric cave on the outskirts of the city of Torquay, in England. At the time she was living with Maury Gurgel Valente, who was pursuing his career as a diplomat, which led them to settle in that location. We read the impressions of that visit in a letter addressed to her sisters:

Yesterday we went to see some ancient, prehistoric caves – from millions of years ago. It was very beautiful. Despite a certain anguish. I left there inclined not to worry about small things, since before me so many years had passed.11

Known as Kent’s Cavern, this set of caves constitutes one of the most important paleontological sites in Europe, since some of the most remote hominid fossils in the region were found there.

Only ten years before Clarice’s visit in 1940, the Grotte de Lascaux, in France, was “discovered,” whose walls contain one of the oldest sets of cave paintings of which we are aware. Along with other grottos or prehistoric caves thus recognized not only in Europe, but also in Africa, the Americas and Asia in the following years, a very particular scenario for theories of the image in modernity was considered, causing a true stir in the history of art, raising issues that have different ramifications on the movements and theories of modern and contemporary art, as well as on the production of several artists.

Five years after Clarice’s visit to the Torquay cave in 1955, the writer and philosopher Georges Bataille visits the Grotte de Lascaux. This long and impressive tour will give rise to one of the most important books to date on the philosophical and artistic impact of the historical recognition of cave paintings for modernity. In Lascaux: Or, The Birth of Art,12 Bataille asserts: “We know next to nothing of the men who left behind only these elusive shadows.” And today it is no different. Almost nothing. We make suppositions, we invent possible stories. Recently, an exhibition at the Centre Georges Pompidou13, in Paris, had as a theme the impact that this new area of research, prehistoric art, had on modern artists, immersing them in this phantasmatic view of that which is “before history.” Prehistory would thus be a modern enigma. We understand how the desire to know the origins of humanity in its relation to art is inseparable from an impulse to recognize these same origins based on the sphere of the enigma. In Bataille’s words, “we are left painfully in suspense by this incomparable beauty and the sympathy that it awakes in us.”

To say the same about the caves painted by Clarice and, by extension, all of her images, would not be an exaggeration. We know “almost nothing,” they leave us likewise in suspense, left to the enigma. We may ask ourselves: would Clarice have transposed, years later, the experience of this visit to the caves of Torquay to the paintings of the caves, as well as to her texts? Or would it be that, as a good reader, she would have accompanied some debate about cave paintings, supposedly the first images made by these humans “without language,” influencing their first forays into the elaboration of their own images? This universe of associations – an underground connection between things – will not be enunciated by the writer, of course, but perhaps, we may suppose, felt by her through contact with the material of painting and words. As a friend and interlocutor of several important Brazilian and foreign artists of the time, Clarice did not paint ignoring the modern debates on art. Thus, despite the timidity and technical fragility of her paintings, they are likewise part of a corpus of works and practices that offer us a scenario of the artistic production of the period. Of course, Clarice would nonetheless never agree with such a statement, she, who in her own words “was never modern.” Clarice was actually ancient, prehistoric, extemporaneous. Basically, in her own words: “when I think a painting is strange that’s when it’s a painting. And when I think a word is strange that’s where it achieves the meaning. And when I think life is strange that’s where life begins.”14

Notes

1 Translated from the Portuguese by Marco Alexandre de Oliveira. The original title was: “O sentido é um sopro: Imagens em Clarice Lispector.”

2 This consultation was part of my doctoral research in visual arts, with an emphasis on history, theory, and art criticism, in the Graduate Program in Visual Arts at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). The dissertation, titled “Escrever um sopro em papel de água viva: imagem e pintura em Clarice Lispector” (Writing a Breath on Living Water Paper: Image and Painting in Clarice Lispector) is available here: http://hdl.handle.net/10183/214321.

3 LISPECTOR, Clarice. Água Viva. Translated by Stefan Tobler. New York: New Directions, 2012, p. 83.

4 LISPECTOR, Clarice. Água Viva. Translated by Stefan Tobler. New York: New Directions, 2012, p. 9.

5 LISPECTOR, Clarice. A Breath of Life (Pulsations). Translated by Johnny Lorenz. New York: New Directions, 2012, p. 43.

6 BORELLI, Olga. Clarice Lispector. Esboço para um possível retrato. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Nova Fronteira, 1981, p. 70.

7 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Meus livros felizmente para mim não são superlotados de fatos, e sim da repercussão dos fatos nos indivíduos.”

8 DELEUZE, Gilles. Logique de la sensation. Paris: Editions de la difference, 1981.

9 BLANCHOT, Maurice. The Space of Literature. Translated by Ann Smock. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989, p. 260.

10 DIDI-HUBERMAN, Georges. Falenas. Translated by António Preto, et al. Lisbon: Imago, 2013, p. 306.

11 LISPECTOR, Clarice. Minhas Queridas. (Ed.) Teresa Montero. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 2007, p. 236. The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Ontem fomos ver umas cavernas antigas – milhões de anos pré-histórica. Foi muito bonito. Apesar de dar certa aflição. Saí de lá disposta a não me preocupar com coisas pequenas, já que atrás de mim havia tantos e tantos anos.”

12 BATAILLE, Georges. Lascaux: Or, The Birth of Art: Prehistoric Painting. Skira, 1955, p. 12-13.

13 DEBRAY, Cécile; LABRUSSE, Rémi; STAVRINAKI, Maria. Préhistoire, Une énigme moderne. Exhibition Catalogue. Paris: Centre National d’Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou, 2019.

14 LISPECTOR, Clarice. Água Viva. Translated by Stefan Tobler. New York: New Directions, 2012, p. 76.