Gurgel Valente, Paulo. At Home With Clarice. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2021. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2021/11/11/at-home-with-clarice/. Acesso em: 27 July 2024.

I believe that Clarice and I shared a common feeling: objects are not inanimate, on the contrary, they have a secret life.1

I do not know if the reader has already tried turning off the lights at night in your room and, little by little, noticed that your eyes adapt to the dark and finally you can perceive the living presence of things.

More than one fairy tale or fictional story has already shown that in a store at night the toys came to life, or even the statues and paintings in a museum are transformed, and in the daytime they return to their realistic functions. Perhaps Geppetto’s Pinocchio is one of the first.

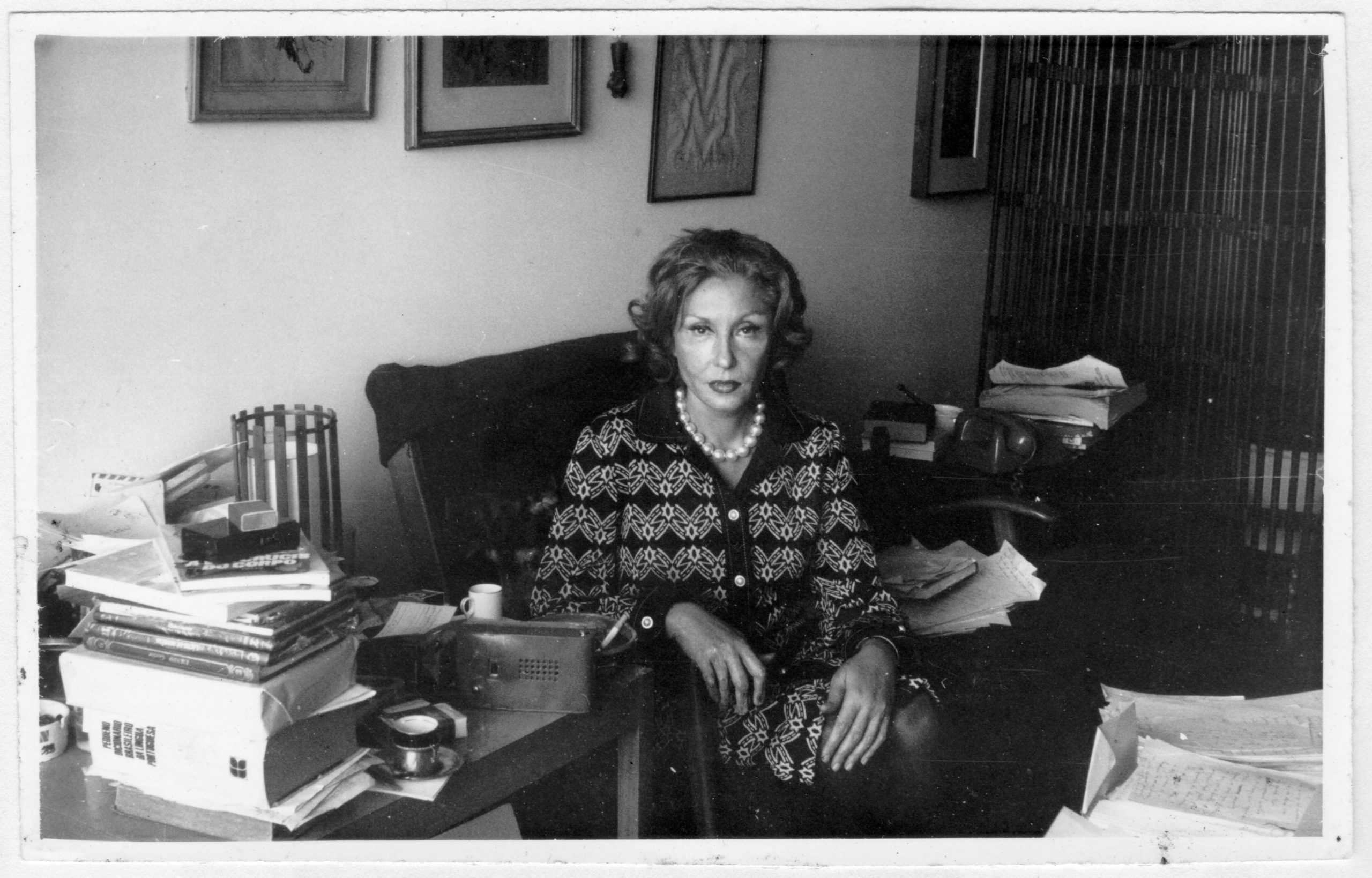

Clarice’s paintings and objects were the setting of her life that made her home a cozy and recognizable place, her nest from where she would fly and to where she would return.

From the “Italian phase,” which refers to the period in which Clarice and Maury arrived in Naples in 1944, he as vice-consul in the south of an Italy that was beginning to be liberated, there are the nude paintings of Savelli and Fazzini, and especially Savelli’s Annunciation, a very colorful and still impressive painting cited and described several times in Clarice’s chronicles, such as in “Annunciation,” published on December 21, 1968:

At home I have a painting by the Italian artist Savelli. I valued it all the more when I learned that he had been commissioned to design the stained-glass windows in the Vatican.

However much I study the painting, I never grow tired of it. On the contrary, I always find something new to admire.

In the painting, the Virgin Mary is seated beside a window and it is clear from her swollen belly that she is pregnant. The archangel at her side is watching her. And the Virgin, as if overwhelmed by the archangel’s message, prophesying her destiny and that of future generations, raises her hand to her throat with surprise and anguish.

The angel, who has entered by the window is almost human: but those long wings remind us that angels can move from one place to another without touching the ground. Those wings are quite human: they appear to be made of flesh and the angel’s face is that of a man.2 (Selected Crônicas, p. 54)

And, in one of the paintings by Savelli (1942), one reads the dedication “a la Signora Valente, comme cordiale ricordo.”

These paintings were apparently purchased for the couple’s first collection, and also for decoration and memorabilia.

In this “Italian phase,” the highlight is her portrait by Giorgio de Chirico, whose description we leave for Clarice herself in a letter to her sisters, Elisa and Tania, dated from Rome, May 9, 1945:

My darlings,

[…] This afternoon was the last time I posed for De Chirico (pronounced De Quirico). He is famous all over the world. He has paintings in almost every museum: you’ve certainly seen reproductions of his paintings. Mine is small; it’s great, a beauty, with expression and all. He charges very much, as is natural, but he charged less. And while he was painting a buyer appeared. He naturally didn’t sell it… But he came up with a story about making two paintings for me to choose. The next time I am in Rome, if my dear husband allows, I will then pose for him only, I mean, for the painting to be his (he would sell it then). My portrait is just of the head, neck, and a little bit of shoulders. Everything in miniature. I posed in that blue velvet dress from the Mayflower, remember Tania? When I take the picture of the painting, I’ll send it. But you might not be able to see it well because of the colors that don’t appear.

[…] I was posing for De Chirico when the newsboy shouted: The war is over! I also shouted, the painter stopped, one noted the strange lack of joy and continued.

After a little while I asked him if he liked having disciples. He said yes and that he intended to have some when the war was over… I said: but the war is over! In part, his phrase came from the habit of repeating it, and in part from the fact that he didn’t even seem to be relieved, exactly.3 (CA, pp. 167-168)

Another reference to the same episode will appear in the audio statement that she gave to the Museum of Image and Sound in Rio de Janeiro, in 1976:

I was in Rome and a friend of mine said that De Chirico would certainly like to paint me. After asking him he said only if he sees me. Then he saw me and said: “I’m going to paint your portrait.” In three sessions he did so and said: “I could go on painting this portrait endlessly, but I’m afraid of ruining everything.”4 (OE, p. 165)

De Chirico needs no introduction, since he is one of the biggest names in the surrealism of his time; I visited his museum-house at the Piazza di Spagna in Rome, where Clarice posed for the portrait.

No longer from the “Italian phase,” but still in the group of portraits of Clarice, there is the one by Jeronymo Ribeiro — at first an unknown portraitist. There is a charcoal on paper from 1942, the time of Clarice’s first publications: short stories in magazines and her debut novel, Near to the Wild Heart. I consider the portrait very faithful, even compared to photographs from the period.

From a little later is the portrait done in 1944 by the poet and diplomat Ribeiro Couto in a small notebook belonging to Clarice herself. The meeting occurred in Lisbon, where Clarice had stopped on her way to Naples. On August 2, she records the conversation with Couto with respect to the brief pencil portrait on the ruled paper:

He said that it was difficult to draw me. There was something that he couldn’t grasp, and the sweetness. That I had three things: childhood, a profound life, and something rough. He said: animality bathed in moonlight. A healthy chin.5

Also noteworthy are the portraits of Clarice and Maury by Alfredo Ceschiatti, completed at a meeting in Paris in January 1947. Clarice’s portrait, defined with very few lines, became celebrated as one of the best interpretations. In Maury’s portrait, the artist himself noted at the end “(un dessin mal réussi),” despite being very faithful. Ceschiatti became more famous as a sculptor, after creating several monuments in Brasília, and was a friend of the couple.

A lifelong object is the porcelain rooster, which was left over from a pair — recorded as Florentine — that has an intense relation with Clarice’s stories with chickens — such as the short story “A Chicken” and the children’s short story/book Laura’s Intimate Life.

In this context is the photograph of a horse, with a curious story: Clarice saw this photo on the derby page of the Jornal do Brasil and immediately asked the newsroom to send it to her, and she made a poster out of the photo. The image conveys a sense of freedom and, as in the case of chickens, horses are everywhere in her work with admiration, both in The Besieged City and in “Dry Sketch of Horses,” from Where Were You at Night, a noteworthy chronicle.

Clarice had great artist friends, such as Lúcio Cardoso, Maria Bonomi, Carlos Scliar, Fayga Ostrower, and Bruno Giorgi, all of whom often gave her gifts in the context of their friendship.

Lúcio Cardoso’s painting deserves special mention. Lúcio was possibly one of Clarice’s first loves, which did not go anywhere; there was a great intellectual affinity between the two at the beginning of both of their careers, although he was older and more experienced. He helped give a title to Clarice’s first book, Near to the Wild Heart, taken from a phrase by James Joyce. She received at least two paintings from her friend: a first one that was very dark and sad, practically all black, from the phase of his stroke, which Clarice gave away, and finally, another very bright one that reflects the moment in which Lúcio was recovering at the Brazilian Beneficent Association for Rehabilitation (ABBR). It is very cheerful and it became a memory of this great friend and mentor. In a chronicle dated January 11, 1969, Clarice speaks of their last meeting:

Some women friends had gathered outside his hospital room. Most of them could no longer bear to watch him lying there, motionless and in a state of coma.

I went into his room and saw the dead Christ. His face had the greenish hue of those portraits by El Greco. Beauty was written all over his features.

Previously, even when he remained silent, at least he could hear me.

Now he would not be able to hear me even if I were to declare aloud that in my youth he had been the most important influence in my life. Lúcio taught me how to discover the real people behind the masks, he also taught me the best way to contemplate the moon. It was Lúcio who transformed me into a fellow – native of Minas Gerais: I passed the test and mastered all those traits I so admire in people from that part of Brazil.6 (Discovering the World, pp. 219-220)

Maria Bonomi was a lifelong friend, and Clarice was godmother to her son Cassio, whom she had with Antunes Filho, ever since she was an art student in Washington, DC, when, at the suggestion of the ambassador Alzira Vargas, she asked Clarice, then Maury’s wife as secretary of the Embassy, to borrow suitable clothing, gloves, a long dress, and shoes to go to a dinner at the White House. From then on, throughout their lives they exchanged opinions about their respective creative processes, which, in my opinion, was consolidated in Água Viva, in which the character is a visual artist. In a special edition of this book, Teresa Montero authors the essay “Água viva: antilivro, gravura ou show encantado” (Água Viva: anti-book, etching or enchanted show), in which she addresses this artistic dialogue.7

Carlos Scliar was also a great friend. A soldier in the Brazilian Expeditionary Force (FEB) in the Italy campaign, he met Clarice at that time, but he already carried Near to the Wild Heart in his backpack. I also remember the two of them at the March of the One Hundred Thousand in 1968, there are good photos that illustrate this moment, and I also recall that Clarice spent a weekend at Scliar’s studio home in Cabo Frio. Both were descendants of Russian Jews, persecuted practically at the same time.

Fayga Ostrower was another great friend, and there was identification with her work, possibly also due to their similar Slavic origins, and Clarice kept her paintings received from the time in which she lived in Washington, with emphasis on the engraving of the mother hugging her baby with great tenderness (Maternity, 1950).

Bruno Giorgi was one of the artists belonging to the “Leme republic” — almost on the same block lived Aloisio Magalhães, Burle Marx, and Bruno Giorgi, the latter in a small vila or quarter off Gustavo Sampaio Street, who at the time was married to Mira Engelhardt — the couple were good friends and I went to Bruno Giorgi’s house a few times, without having any idea of his importance. The sculptures that Clarice received are scaled-down versions of Brasilia’s important monuments.

A part of Clarice’s work, very well described in Clarice jornalista (Clarice the Journalist), by Aparecida Nunes, was to interview noteworthy people, for whom she always brought her books as gifts. It occurs that some of the interviewees, such as Djanira da Motta e Silva and Grauben, gave her paintings in return. It is clear how Clarice in these interviews, almost always due to her admiration and perception and interest in the “other,” developed an affective relationship with these people. In Djanira’s case, the affection was defined before the meeting, and was directed toward both the person and the work, as one can read in the lines that begin the transcription of the interview: “How not to love Djanira, even without knowing her in person? I already loved her work so much — so much.”8

As for the meeting with the painter Grauben, it is portrayed in a chronicle in which Clarice describes the canvas she brought home:

I chose a painting that is all Grauben: a large blue bird somewhere between an eagle and a peacock, a huge butterfly, a fully open flower, plants, and all the dots that she uses as background for the painting and that give the impression of a bush of joy.9 (CR, p. 142)

It is easy to see that Clarice’s “setting” — from which she created and, why not, levitated — was created by her affectivity, whether by the objects in themselves or by the people involved and permanently intertwined in them, throughout her life and work.*

Notas

1 Translated from the Portuguese by Marco Alexandre de Oliveira.

2 Clarice Lispector, “Annunciation.” Selected Crônicas. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. New York: New Directions Publishing, 1996.

3 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Minhas queridas […] Hoje de tarde posei a última vez para De Chirico (pronuncia-se De Quírico). Ele é famoso no mundo inteiro. Tem quadros em quase todos os museus: certamente vocês já viram reproduções dos quadros dele. O meu é pequeno; está ótimo, uma beleza, com expressão e tudo. Ele cobra muito caro como é natural, mas cobrou menos. E enquanto ele estava pintando apareceu um comprador. Ele naturalmente não vendeu… Mas veio com uma história de fazer dois quadrinhos para eu escolher. De outra vez que eu estiver em Roma, se o excelentíssimo marido permitir posarei então para ele mesmo, quer dizer, para o quadro ficar dele (ele venderia então). O meu retrato é só da cabeça, pescoço e um pouquinho de ombros. Tudo diminuído. Posei com aquele vestido de veludo azul da Mayflower, lembra-se Tania? Quando tirar a fotografia do quadro, mandarei. Mas não se poderá talvez ver bem por causa das cores que não saem. […] Eu estava posando para De Chirico quando o jornaleiro gritou: É finita la guerra! Eu também dei um grito, o pintor parou, comentou-se a falta estranha de alegria da gente e continuou-se. Daqui a pouco eu perguntei se ele gostava de ter discípulos. Ele disse que sim e que pretendia ter quando a guerra acabasse… Eu disse: mas a guerra acabou! Em parte, a frase dele vinha do hábito de se repeti-la, e em parte do fato de não ter mesmo a impressão exata de um alívio.

4 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Eu estava em Roma e um amigo meu disse que o De Chirico na certa gostaria de me pintar. Aí, perguntou e ele disse que só me vendo. Aí me viu e disse: ‘Eu vou pintar o seu retrato.’ Em três sessões ele fez e disse assim: “Eu poderia continuar pintando interminavelmente esse retrato, mas tenho medo de estragar tudo.”

5 The notebook has been in the collection of the Moreira Salles Institute since 2012, and is available for reading at the claricelispector.ims.com.br websitesite with the title Logbook. [The original in Portuguese reads: “Disse que era difícil me desenhar. Tinha alguma coisa que não se pegava, e a doçura. Que eu tinha três coisas: infância, vida profunda e alguma coisa áspera. Disse: animalidade banhada de luar. Queixo saudável.”]

6 LISPECTOR, Clarice. Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet, 1992.

7 LISPECTOR, Clarice. Água viva — Edição com manuscritos e ensaios inéditos. Edited by Pedro Vasquez. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 2019.

8 WILLIAMS, Claire (ed.). Entrevistas — Clarice Lispector. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 2007, p. 198. [The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Como não amar Djanira, mesmo sem conhecê-la pessoalmente? Eu já amava o seu trabalho, e quanto — e quanto” (free translation)]

9 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Escolhi um quadro que tem tudo da Grauben: um grande pássaro azul entre águia e pavão, uma enorme borboleta, uma flor toda aberta, plantas e todos os pontilhados que ela usa como fundo do quadro e que dão a impressão de uma moita de alegria”.

* I am grateful for the collaboration of Teresa Montero, author of the biography Clarice Lispector — Eu sou uma pergunta (Clarice Lispector – I Am a Question; Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 2021).