, Manuscripts of A Breath of Life. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2018. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2018/05/15/manuscritos-de-um-sopro-de-vida/. Acesso em: 26 July 2024.

In February of this year, the second part of the original manuscripts of A Breath of Life was delivered by the writer’s son, Paulo Gurgel Valente, to be incorporated into the Clarice Lispector Collection, which, under the care of the IMS, has contained the first part of the novel since 2004, when it arrived here alongside other documents.

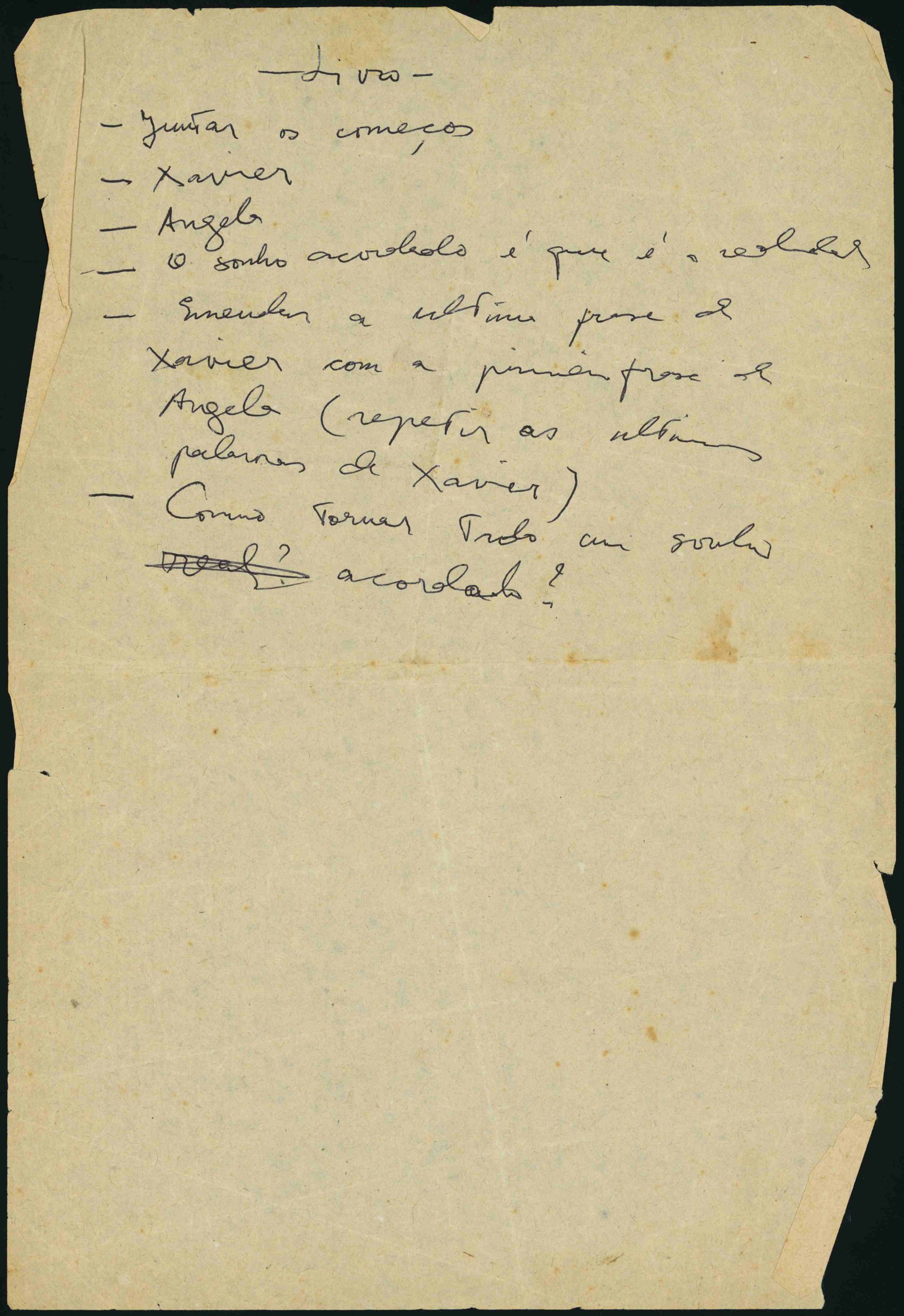

This is a complex book to edit. In 1977, the year of the author’s death, the writings, at that time sparse and on separate sheets, had not yet been organized by Clarice. The posthumous publication was the responsibility of Olga Borelli, according to her opening note to the first edition, in 1978:

For eight years I lived with Clarice Lispector, participating in her creative process. I wrote down her thoughts, typed her manuscripts and most of all shared in her moments of inspiration. As a result, she and her son Paulo entrusted me with the organization of the pages of A Breath of Life.

This explanatory note, however, disappeared from the most recent editions, leaving new readers with the impression that Clarice had conceived the book as published. Invited by the Moreira Salles Institute, Portuguese professor and critic Carlos Mendes de Souza – a specialist of Lispector’s work and author of Clarice Lispector: figuras de escrita (Clarice Lispector: Figures of Writing) – came to Rio with the task of examining the manuscripts and comparing them with the book. The scholar noted that some observations can already be made:

Most of these fragments show an indication of belonging to the lines of Angela and the author, but we also come across some fragments that refer to names and speeches of characters not included by Olga Borelli in the book. It was probably an aborted project on Clarice’s part, since in the work A Breath of Life, as we know it, we only find indications of Angela and the author. On the other hand, there are still some manuscripts with an explicit reference to these characters that were not included by Olga Borelli in A Breath of Life, but were in the book Clarice Lispector: Esboço para um possível retrato (Clarice Lispector: A Sketch for a Possible Portrait).

The study of the originals of A Breath of Life, which go back to the same writing period as The Hour of the Star (1974 to 1977), also under the care of the IMS, will continue next year, in Portugal, where Mendes de Souza is a professor at the University of Minho.