, "In the Name of My Father". IMS Clarice Lispector, 2025. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2025/02/13/in-the-name-of-my-father/. Acesso em: 05 February 2026.

Clarice Lispector wrote deliberately political texts. To name a few, “A Letter to the Minister of Education,”1 in which she defends student access to vacancies at public universities; “The Killing of Human Beings: the Indians,”2 in which she repudiates the murder of indigenous people for the exploitation of natural resources and advocates for the demarcation of their territories; and “Mineirinho,” in which she censors the action of the police in murdering a criminal with thirteen gunshots. Clarice also participated in a few gatherings against the dictatorship and was present at demonstrations, including the March of the One Hundred Thousand, which was recorded in photographs in which she appears in the middle of the crowd in front of the Rio de Janeiro City Council Building, or alongside Carlos Scliar, Glauce Rocha, Oscar Niemeyer, and Milton Nascimento, among other public cultural figures.

Despite this, Clarice was accused of being alienated by the patrol at Pasquim, a cultural tabloid formed by illustrious men from the upper-class areas of Rio de Janeiro, more specifically by the cartoonist Henfil. The spat had negative repercussions and the cartoonist, with caricatured reasoning, defended himself: “I placed her in the Cemetery of the Living Dead because she places herself inside a Little Prince dome, to remain in a world of flowers and birds, while Christ is being nailed to the cross. In times like these, I only have one word to say about people who keep talking about flowers: they are alienated.”3 The writer’s burial promoted by the cartoonist (in his column called “Cemetery of the Living Dead”) happened in 1972, therefore a few years after the political texts published by Clarice during Institutional Act No. 5 (AI-5) and the March of the One Hundred Thousand. Teresa Montero shows in Clarice’s biography that the writer was registered by the National Information Service (SNI), a spy agency of the dictatorial government.

But the fact is that Clarice’s connection with politics does not take place on the surface of public life, or in the texts that directly address the issue. This is due to the writer’s understanding of the rift between art and politics, which is addressed in two related texts, “Literature and Justice” and “What I Would Like to Have Been,” in which she observes with disconcerting lucidity the uselessness of her literature as a political instrument. In the former, she says:

[…] my tolerance in relation to myself, as someone who writes, is to forgive my inability to deal with the “social problem” in a “literary” vein (that is to say, by transforming it into the vehemence of art). Ever since I have come to know myself, the social problem has been more important to me than any other issue: in Recife the black shanty towns were the first truth I encountered. Long before I ever felt “art”, I felt the profound beauty of human conflict. I tend to be straightforward in my approach to any social problem: I wanted “to do” something, as if writing were not doing anything.

Clarice says that she would like to “deal with the ‘social problem’ in a ‘literary’ vein (that is to say, by transforming it into the vehemence of art).” She therefore dissociates two dimensions, which are irreconcilable for her: the aesthetic and the social. She says that she wishes her literature could reach an expression – a “vehemence” – that would bring it closer to the truth with which she felt the “social problem,” which was even prior to the truth with which she felt art. She declares the failure of her literature as a political instrument, which she rightly deems innocuous for the production of effective changes in the social reality, but she also hesitates regarding the aesthetic-formal strength of her literature in dealing with the social, since, according to her, the expression of her writing falls short of that of the “social problem.” In other words, she would have wished to provoke in the reader a rapture similar to the one that she felt in the face of the blatant injustice of wretched families living in shacks built with scrap wood and floating precariously on sticks in the mangrove of her city, Recife; but she declares herself incapable of giving form to this feeling.

Once literature and the “social problem” have been dissociated, she confesses to feeling ashamed for doing nothing. Here, she is no longer speaking of literature and no longer addressing the desire for a vehement writing, but the desire for action: “I wanted ‘to do’ something, as if writing were not doing anything.”

In the second text, which is titled “What I Would Like to Have Been,” Clarice once again addresses the feeling of injustice that assailed her when she visited the slums of Recife and how, in the face of such injustice, she made a commitment to defend people’s rights – “And what I saw made me promise myself that I would not allow that to continue. I wanted to act.” She also observes in this text that as a girl it is as if she had before her two paths to follow, two vocations, and asks herself: “Why did fate determine that I should write what I’ve written, rather than developing in me the that fighting quality?”

It is important to note that in both texts, the word fighting appears repeatedly. She says “profound beauty of human conflict,” in which, curiously, the attribute of beauty, as confronted as it is associated with the work of art, is transposed to qualify struggle and not literature, which is yet another indication of the co-movement that Clarice finds both in the “social problem” and in art. And she ends the text by showing herself to be dissatisfied with the ineffectiveness of literature in the field of political transformations: “What I would like to be is a fighter. I mean, someone who fights for the good of others. […] I ended up being a person who seeks out her deepest feelings and finds words to express those feelings. That is very little, very little indeed.”

The two astonishments of the young Clarice become manifest: the truth of the “social problem” and the truth of art; two truths like two divergent paths to follow: one collective, the other individual; one exterior, the other interior; one concrete, the other abstract; one conscious, the other unconscious; one political, the other artistic; one of action, the other of imagination; one real, the other fictional. Two truths that create an unceasing tension in her work, the culmination of which will be the story – “exterior and explicit” – of Macabéa, in The Hour of the Star, which was published by Clarice shortly before her death.

It is important to emphasize that struggle, whose seed is revolt, will be the guide for Clarice’s feeling of justice. Before choosing the truth of art and becoming a writer, between the two paths that moved her, she followed the path of struggle and entered the National School of Law. As she said in an interview: “my idea was to study law to reform the penitentiaries.”4 During her undergraduate studies, she published an essay in the school journal called “Observações sobre o direito de punir” [Observations on the Right to Punish], in which she traces the genesis of the emergence of law, the conclusion of which will be that law is born of revolt and institutionally guarantees its perpetuation:

In the beginning, there were no rights but powers. Since man was able to avenge the offense directed at him and certified that such a revenge satisfied him and discouraged second offenses, he only stopped exercising his strength in the face of a greater force. […] The weak united; and it was then that the plan properly began […] the weak, the first clever and intelligent people in the history of humanity, sought to submit those relations that until then had been natural, biological, and necessary to the domain of thought. As a defense, the idea arose that despite not having power, they had rights. […] And in the mind of man what corresponded to that revolt was being formed.5

Law is thus “what corresponded,” in its form, to “that revolt” of the weakest against the strongest. Revolt, as the actual etymology of the word suggests, is at the beginning and end of law, never ceasing to return, to revolve; it is raw material and a work in progress. It is like lighting a fire in a fire, not to let it be extinguished once it is controlled. It is worth observing, in the story told by Clarice, the occurrence of a significant change between the first moment, when the revolt is individual (or transindividual), the ferment of law, and the second moment, when it is fixed in the impersonal form of law, which guarantees the right to fight, which then becomes political. Between one and the other, the status of the revolt changes, from individual to collective.

Nonetheless, Clarice ponders, the whim of judges can infiltrate the impersonal application of law, thus making it dysfunctional. This is where the snake bites its tail. Because, if law is impersonal, the application of law, which is in the power of people designated for such a purpose, is not. That being the case, revolt – we could also call it “civil disobedience” with Thoreau – is the driving force of justice, that is, it renews, in a dynamic that successively goes from the individual to the collective and from the collective to the individual, the health of a political system. Such an individual dimension of revolt – against a dysfunctional justice system that oppresses, punishes, maintains the privileges of certain social strata, and, in short, eliminates the possibility of struggle – is ingrained, as we will see, in Clarice’s work.

*

Let us look at individual revolt – or its annihilation – in two of Clarice’s characters who are unexpectedly similar. The first, Joana, is from her debut novel Near to the Wild Heart, which was written when the author was 20 years old, and the second, Macabéa, is from The Hour of the Star, the last book published during her lifetime. Between the former and the latter books, the author’s entire adult life passed.

The character Joana, after her father’s death, comes to live with her aunt. One day, when she was accompanying her shopping, while she was leaving the store she puts a book under her arm and leaves without paying. Her aunt turns pale and then they have the following conversation:

“Do you even know what you did?”

“Yes . . .”

“Do you know . . . do you know the word . . .?”

“I stole the book, isn’t that it?”

“But, Dear Lord! Now I’m at a complete loss, as she even confesses to it!”

“You made me confess, ma’am.”

“Do you think it’s alright . . . it’s alright to steal?”

“Well . . . maybe not.”

“Why then . . .?”

“I can.”

“You?!” shouted the aunt.

“Yes, I stole because I wanted to. I’ll only steal when I want to. There’s no

harm in that.”

“Lord help me, when is there harm in it Joana?”

“When you steal and are afraid. I’m neither happy nor sad.”

Her aunt gazed at her in distress.

“My dear, you’re almost a woman, soon you’ll be all grown up . . . In no

time we’re going to have to let down your dress . . . I beg you: swear you won’t

do it again, swear, swear for the love of our heavenly Father.”

Joana looked at her curiously.

“But if I’m saying that I can do anything, that . . .” Explanations were

useless. “Yes, I swear. For the love of my father.”

The revolt here is a youthful experiment, a mere petulant exercise in disobedience, but I would like to retain its potency. The feeling of being able to say no to the law is equivalent to saying yes to oneself; a self-affirmation. In this sense, we will see how Joana is different from Macabéa, although both share some similarities in personality. I will take advantage of a detail in the dialogue to make a brief detour and discuss the importance of Clarice’s father for her notion of justice, which is linked to the value of the human person.

Although the standard translation into English reads “for the love of my father,” the original phrase in Portuguese, “em nome do pai,” should rather read “in the name of the father,” a Christian formula that coincidentally served Jacques Lacan to forge his metaphor of the law – “the name of the father,” whose sound, in French, is le nom du père, which also sounds like “the no of the father.” For the French psychoanalyst, it is this no from adults that establishes in the child the superego with which its self will have to negotiate during group life. In the dialogue created by Clarice, the superego, which is embodied in the figure of her aunt, a follower of conventions, says that one cannot steal, but Joana’s unruly self disagrees and steals because she can and is not afraid. Once the girl realizes that her aunt would never understand her arguments, she cynically accepts her plea and promises not to steal anymore, “in the name of my father.” Joana’s dead father, unlike her aunt, did not represent the figure of imposing law for the character; when he was alive, Joana, in reciting verses to him, received the answer yes: “Lovely, darling, lovely. How do you make such a beautiful poem?” Thus, when she promises to no longer steal in “the name of my father,” although she seems to cede to her aunt’s request, she refuses and remains loyal to her paternal affiliation, in opposition to the Lacanian metaphor, that is, by singularizing the figure of her father.

Clarice’s father was a Ukrainian immigrant with a penchant for the arts, mathematics, and spiritual things, but for being Jewish, when he was young he was rejected by the universities where he wanted to study. Once in Brazil, he worked in a soap factory and as a peddler. As Clarice wrote in the column “Persona,” the greatest compliment given to someone by her father was to say that he or she was “a person;” “To this day I still say it, as if it were a maxim to be applied to anyone who has won a fight, and I say it with a heart that is proud to belong to the human race: he or she is a person. I’m grateful to my father for having taught me early on to distinguish between those who are truly born, live and die, from those who, as people, are not persons.” Pedro Lispector died when Clarice was 18 years old. In a letter to her friend Fernando Sabino, she said that her father had once told her: “if I wrote, I would write a book about a man who realized he had lost his way;” and she concluded: “I can’t think about it without feeling unbearable physical pain.”6

Pedro Lispector’s life was not what one wished due to his situation, in this case, being Jewish in Ukraine, at a time when one’s people were being persecuted. For someone like Clarice, who scrutinizes the materiality of life with such acuity that she dedicated all of her literature to trying to get closer to its mystery, this is the greatest injustice: a human being prevented, by social and material conditions, from being what one wants. Clarice’s view coincides with that of another Jewish woman, Hannah Arendt, who pursues the value of the singularity of the human being based on the idea of natality (an idea made philosophically important by Christianity). As Arendt says in The Human Condition:

[…] the new beginning inherent in birth can make itself felt in the world only because the newcomer possesses the capacity of beginning something anew, that is, of acting. In this sense of initiative, an element of action, and therefore of natality, is inherent in all human activities.

What social and material conditions can repress is precisely the possibility of action, necessarily political action; in other words, the flowering of revolt and of the possibility of struggle. In the case of an unjust society, the no of the capricious and personal law is a no to the political action of those in need. Macabéa, for example, a character in The Hour of the Star, had her life assailed by the impersonal machine of the economic and political system. Let us remember her story, which is narrated by another character, Rodrigo S.M. (actually Clarice Lispector); this is how, with her own name in parentheses, the writer introduces the author-narrator, thus confusing herself with him.

Rodrigo S.M. is a middle-class intellectual (although he says that he does not belong to any class) and he tells the story of a northeastern girl (like him) whose “feeling of perdition” on her face he caught at a glance on a street in Rio de Janeiro. He makes a point of emphasizing that she is a fictional creation of his, even though she looks like “all those northeastern girls out there.” Macabéa is a disturbing character. She is dreamy, poetic, and sensual; nonetheless, these qualities do not germinate in her. As Clarice said in an interview, Macabéa has “a trampled innocence.” The narrator, at one point, says that the character “had what’s known as inner life and didn’t know it.” Mistreated by the author, even though he oscillates between hatred and love for his creation, Macabéa is massacred by the big city and humiliated by people close to her. She did not react to anything.

Joana, from Near to the Wild Heart, is also dreamy, poetic, and sensual. It is as if the material from which the two were made – manifested in the booming “inner life” – was the same, but, in Joana, this original material “could be perfected,” the result of which will be a reflective, confident and active woman, while, in Macabéa, this same matter atrophied – like her “ovaries shriveled as a cooked mushroom” – and produced the deformed fruit “of a cross between ‘what’ and ‘what.’” The theme of perfecting and learning permeates many of Clarice’s books; for her, this means the self-discovery of evil, of disobedience, of insubmission, of the affirmation of desires against the castrating and unjust superego. In other words, it means revolt against the law. And why do Macabéa and Joana, although made of the same material, become the opposite of each other?

The Hour of the Star begins with the phrase: “all the world began with a yes.” This was Macabéa’s first “yes,” her birth. After all, her life was conceived. With this yes of natality, the character introduces the germ of “the capacity of beginning something anew, that is, of acting,” using the words of Hannah Arendt. But – and this is the consternation of the book – Macabéa, between the first yes, that of birth, and the second, that of her death, was riddled – as was the criminal Mineirinho with thirteen bullets – by noes: she did not have a father, she did not have a mother, she was not pretty, she was not intelligent, she was not attractive, she was not loved. On the contrary, she was only mistreated by her aunt, her work friend Glória, her boyfriend Olímpico, and the big, impersonal city. Macabéa was marked by the insignia of no. Like cattle, anonymous, among so many others, her destiny was the slaughterhouse; or like Clarice’s chickens, the pan.

What Clarice does in The Hour of the Star is install an inexorability regarding Macabéa’s destiny, which founded on the immobilizing inequality of Brazilian society, whose slaveholding origin is permeated by an unequal and punishing economic system for the poorest. Macabéa does not have “the right to scream” – this is one of the possible titles for the book, among the 13 that Clarice lists. A life born of yes, yet despoiled by noes. Any of Macabéa’s desires, from the beginning, was reprehended and scorned. Even the ones that she allowed herself to nourish were not hers, but from advertisements heard on the radio, in the cinema, in store windows. In other words, the market even alienated her from what could have been most vital, her desires; “she like a stray dog was guided,” a plaything of a logic that deindividuated her, thus making her one more of the servile masses – “She didn’t even realize she lived in a technical society in which she was a dispensable cog.”

Clarice, in her merciless and ironic text, emulates the oppression of the system and its noes, even taking common-sense phrases such as: “She wanted more because it really is true that when you give that sort an inch they want the whole mile, your average Joe dreams with hunger of everything. And he wants it but has no right to it, now does he?” Her writing, in The Hour of the Star, seeks to exacerbate a discourse that already exists diffusely in society, thus triggering, without value judgment, from its overexposure, the sadism, oppression, and racism of the middle and upper classes.

An exception should be made for the narrator (actually Clarice Lispector), who occupies an in-between space, and who, despite identifying and sympathizing with the life of that miserable woman, does not abandon his comfort nor can he do anything to save the life of his creation. Rodrigo S.M. spends a large part of the book not knowing how Macabéa’s end will be, whether she dies or not, trying to save her, but without having control over her destiny. In the text, reality speaks louder than fiction. The creator having to kill his creature is a testament to the impotence of an apathetic middle class, but also a confession of class crime, since doing nothing (“as if writing were not doing anything”) is similar to becoming an accomplice of necropolitics; he did not kill her, but he let people kill her. An alternative title of The Hour of the Star is precisely “It’s All My Fault.”

While political struggle is, for the wronged people, a requirement, because life and death depend on it, for the intellectual middle class, which is represented by Rodrigo S.M., it is a choice, about which Clarice says she is ashamed of doing nothing (the privilege of being able to choose between fighting or paying for the service of private security, education, health services, etc.). The shame for doing nothing, in The Hour of the Star, turns into guilt. Despite the identification of Rodrigo S.M. with Macabéa – “I just died with the girl,” he says – this does not prevent him from thus ending the book and saying goodbye to the reader:

And now — now all I can do is light a cigarette and go home. My God, I just remembered that we die. But — but me too?! Don’t forget that for now it’s strawberry season. Yes.

The novella begins with a yes and ends with a yes. The final yes marks both the apotheotic death of Macabéa, who is run over by a luxury car, and the hedonism of the intellectual narrator: “Don’t forget that for now it’s strawberry season.”

*

In 2023, the writer Conceição Evaristo published the book Macabéa: Flor de Mulungu [Macabéa: Mulungu Flower], composed of a short story and illustrations (by Luciana Nabuco), in which the narrator, identifying herself with the character, saves her life: “Macabéa was going to give birth to herself. A mulungu flower had the power of life. The driving force of a people who resiliently frame their scream.”7 The word scream resonates here with one of the alternative titles of Clarice’s novella, as we have already seen, which in this case was denied to Macabéa and is claimed by Evaristo. The choice of the author from Minas Gerais returns to us the question posed at the beginning of this text: the relationship between literature and politics.

Saving a fictional character’s life or not will not, of course, have an effect on preserving the life of a real person. But Evaristo’s intention seems to suggest something more: that the erasure of the original story, which is told by Rodrigo S.M., an author who, although driven by an avid and somewhat frustrated desire to identify with the character, is living in the bourgeois comfort of his home, could, by appropriating the narrative voice, promote effects in reality. In this regard, the title of one of her most discussed short stories, “A gente combinamos de não morrer” [“We Did Agreed To Not Die”], published in the book Olhos d’água [“Eyes of Water”], is exemplary. Macabéa: Flor de Mulungu is also part of a writing project that somewhat seeks to unsay Clarice’s formulations in “Literature and Justice,” that is, it is marked by the porosity between fiction and reality, individuality and collectivity, poles that coexist in the concept of escrevivência [“writing-living”]. To quote Evaristo:

Escrevivência [“writing-living”] can be as if the subject of writing were writing itself, it being the fictional reality, the very inventiveness of its writing, and it often is. But, in writing itself, its gesture expands and, without escaping itself, it collects lives and stories from its surroundings. And that is why it is a writing that does not exhaust itself, but deepens, expands, encompasses the history of a collective.

The writing of Clarice Lispector in the voice of Rodrigo S.M. starts from a different place. There is also porosity between fiction and reality, but the two dimensions are entangled in the text and, supposedly, from there they do not escape. For Clarice, however, it is the transit between the individual and the collective, or between the work and its impact on the reader, that prevents literature from being a political instrument, since the writer writes from an isolated place, without the ballast of belonging to a collective, for its part replaced by the idea of the citizen-consumer, a cog in the gears of the capitalist economic system and of minimalist democracy. Since the struggle can only be collective, the narrator’s feeling of impotence is unavoidable.

Evaristo, on the contrary, writes based on the experience of someone who had society and the state and police apparatus against her: she is black, she lived in a favela, she was a domestic worker. Just like the greater part of the Brazilian Afro-diasporic population, she was socialized in ways of life inherited from her African ancestry, in enclaves of counter-colonial resistance founded on bonds of affective and political belonging, which were carried out, for example, in quilombos, terreiros, and favelas (which were not incidentally called communities). Thus, to save Macabéa in fiction is related to the affirmation of her own existence and that of so many black women writers who today, as a result of a struggle waged collectively over many decades, enjoy a more systematic opening in the publishing market to tell their own stories, which were previously expropriated by writers from the ruling classes.

The appropriation of the self-narrative had a paradigmatic milestone in Brazilian literature with the publication, in 1960, of the book Child of the Dark, by Carolina Maria de Jesus, which was translated into 14 languages. There is a photo in which Carolina and Clarice appear side by side. On the occasion, they were autographing their respective books at a literary event. Carolina would have told Clarice that she wrote elegantly, and Clarice, that Carolina wrote truthfully. Somehow, truth for Clarice can be translated by her own desire to write with the vehemence of the “social problem.” Vehemence should be understood as a writing pregnant with reality, a writing made of words at the same time extracted from the ground, from things, from bodies, with all of their harshness, as if they bore fragments of life that could hurt the reader; and enchanted, capable of making the physical property of their sounds resonate in the rib cage, thus (re)creating what is concrete in the world, that is, giving aesthetic form to revolt, to the “beauty of struggle.” As Chico César sings in “Béradêro,” they are words that “are sounds, are sounds that say yes, are sounds, are sounds that say yes, are sounds [….].”8

But if Carolina in her time was a solitary trailblazer, a representative of the exceptional value of the poor black woman who managed to write against the grain of the city, today, the fact that Evaristo and other black women, as well as writers from other historically silenced representations, are able to write is due less to literature itself than to the struggle of black social movements for public State policies that created conditions for artistic singularities to flourish in the heart of the collective, public policies that were put into practice in more or less recent years, in any case, over thirty years after the publication of The Hour of the Star. This shows us that such changes, even though they suffer too much resistance from the ruling classes, occur as indispensable sutures in the Brazilian social fabric. To list a few: Bolsa Família (Family Allowance), affirmative action in public universities, University For All (PROUNI), the creation of federal institutes, the substantial increase in the number of federal universities, and Law 10,639/03, which regulates the teaching of Afro-Brazilian history and culture in elementary, middle, and high schools. These policies have had and still have an effective impact on people’s lives; they are the ones that effectively save Macabéas, in fiction and in real life, as seems to have been the unattainable wish of the intellectual Rodrigo S.M.

Thus, the fact that Evaristo was able to save the life of her Macabéa is proof, now yes, of a writing that is like a doing, since the act of writing or of making oneself heard literarily was achieved at the heart of collective and individual revolt, of the transformative power of natality, a driver of yeses, from which it is inseparable. But we can also think about Clarice’s own life, at 18 years old, a poor immigrant orphan, seeing herself in the image of her father, “a man who saw he had lost himself,”9 prevented from being what he wished to be by the stigma of being Jewish. After all, she could have become Macabéa. We can even hear the words of Rodrigo S.M. (actually Clarice Lispector) resonating: “When I think that I could have been born her [Macabéa] — and why not? — I shudder. And it seems to me a cowardly avoidance the fact that I am not, I feel guilty as I said in one of the titles.” It is not a rhetorical question: how not to associate the “watery orangeade and stale bread,”10 which Tânia, Clarice’s sister, said had been the family meal at their poorest moment, with the “hot dogs [….] and soft drinks,” the basis of Macabéa’s diet?

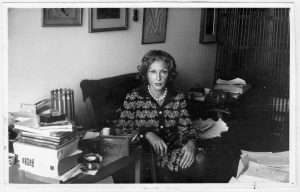

Clarice wrote her story at a mature age (she was 56 years old), a period in which she was still resented the accusation of being an alienated writer. Already far from the poverty of her childhood, living in her upper-middle-class apartment in the Leme neighborhood and having only writing as an instrument of action in the world, she felt politically powerless. The author’s unsuccessful attempt to save Macabéa seems to be the result of a nihilistic disbelief in the possibility of achieving the radical otherness for which she yearned in the context of a society split by extreme injustice. Alone with her writing – and based on the understanding that political struggle is done collectively – she saw no other ethical solution for her literature than to kill her character: “And the word can’t be dressed up and artistically vain, it can only be itself.”

If Clarice, as we saw in the text “What I Would Like to Have Been,” having wished to be a fighter, finds that it is “very little, very little indeed” to be someone “who seeks out her deepest feelings and finds words to express those feelings,” in the same vein, as José Miguel Wisnik well disagrees, in the podcast Clarice Lispector: visões do esplendor (“Clarice Lispector: Visions of Splendor”), it is necessary to understand that

this writer who is so internalizing, so focused on issues of subjectivity, as we would say, actually does what literature does when it is powerful, which is in the same dimension as the subjective having an ontological survey of the world where the social appears with full force.

Somehow, Clarice made use of her right to scream, which is manifest in her writing, whose expressiveness originates in the vehemence of reality, the very one which she complained about not having attained, but which The Hour of the Star bears witness to the contrary. Art may not be political action itself, but it is a political object and source for an ethical apprenticeship that achieves consequential political actions which are pregnant with effects in reality. Furthermore, for Clarice, the true creator of Macabéa, “any cat, any puppy is worth more than literature.”

- [Translator’s note: The original in Portuguese is titled “Carta ao Ministro da Educação.”] [↩]

- [Translator’s note: The original in Portuguese is titled “A matança de seres humanos: os índios.”] [↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “Eu a coloquei no Cemitério dos Mortos-Vivos porque ela se coloca dentro de uma redoma de Pequeno Príncipe, para ficar num mundo de flores e de passarinhos, enquanto Cristo está sendo pregado na cruz. Num momento como o de hoje, só tenho uma palavra a dizer de uma pessoa que continua falando de flores: é alienada.”] [↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “minha ideia era estudar advocacia para reformar as penitenciárias.”] [↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “De início, não existiam direitos, mas poderes. Desde que o homem pôde vingar a ofensa a ele dirigida e verificou que tal vingança o satisfazia e atemorizava a reincidência, só deixou de exercer sua força perante uma força maior. […] Os fracos uniram-se; e é então que começa propriamente o plano […] os fracos, os primeiros ladinos e sofistas, os primeiros inteligentes da história da humanidade, procuraram submeter aquelas relações até então naturais, biológicas e necessárias ao domínio do pensamento. Surgiu, como defesa, a ideia de que apesar de não terem força, tinham direitos. […] E no espírito do homem foi se formando a correspondente daquela revolta.”][↩]

- Translator’s note: the original quotes in Portuguese read: “se eu escrevesse, escreveria um livro sobre um homem que viu que se tinha perdido;” “não posso pensar nisso sem que sinta uma dor física insuportável”.[↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “Macabéa ia se parir. Flor de Mulungu tinha a potência da vida. Força motriz de um povo que resilientemente vai emoldurando o seu grito.”[↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portugueses reads ““são sons, são sons de sim, são sons, são sons de sim, são sons (….).”] [↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads “um homem que viu que se tinha perdido.”] [↩]

- [Translator’s note: the original quote in Portuguese reads: “laranjada aguada e pão amanhecido.”] [↩]