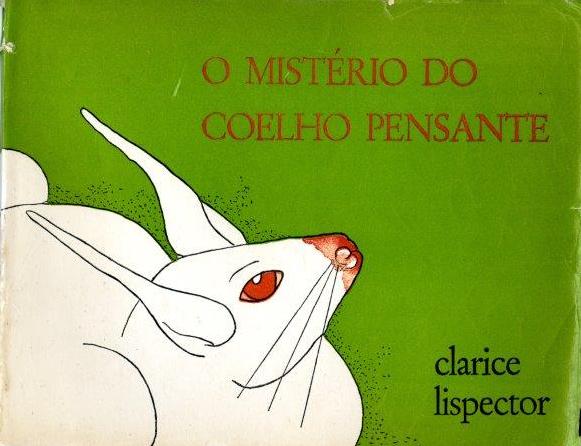

, 50 years of The Mystery of the Thinking Rabbit. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2017. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2017/06/26/50-anos-de-o-misterio-do-coelho-pensante/. Acesso em: 15 December 2025.

Written in the 1950s, during the period in which she lived in Washington, The Mystery of the Thinking Rabbit was the first children’s book written by Clarice Lispector. After a question by her son Paulo – “Why do you only write books for adults? Not for children?” – the text, initially not intended for release, was written in English and shelved until 1967, when it was published by José Álvaro.

The narrator in The Mystery of the Thinking Rabbit is named Paulo, which evokes the name of Clarice’s son and will strengthen the close ties with the reader, since the narrative is constructed like an intimate conversation, where the one who listens/reads is constantly engaged.

The plot focuses on Joãozinho the rabbit, who smelled of ideas, and invents a way to leave his cage when there is no food. The humans notice and do not forget to feed him. Nonetheless, the rabbit wants much more than what the humans offer him, and his life comes to be “eat well and escape, and always with a beating heart.” More than for the adventure, the rabbit had acquired a taste for freedom, and it is outside the cage that he really manages to be a thinking rabbit.

According to Rosa Gens, “Lispector’s poetics is evident in the fluid plot, in the doubts and inquiries, in the presence of a narrator who is always together with the reader and does not know all the answers, allowing the doubt to be prolonged. Mystery narratives commonly lead the reader to investigate clues, elaborate solutions, solve enigmas. In Clarice Lispector’s writing, the mystery is different. It does not concern an enigma related to facts, only the possibility of pretending to be a rabbit, of climbing into someone else’s skin, of thinking from different angles. In the text, which emphasizes fantasy and imagination, playing and thinking provide the tone, and the contamination between rabbit and human, emphasized at the end of the narrative, makes way for the marvelous.”

A book only for those who like rabbits, according to Clarice Lispector, who moreover asks adults for a little patience and understanding for the many questions that cannot be answered in rabbit terms.