, Illustration and Affect, A Conversation with Mariana Valente. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2017. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2017/04/10/ilustracao-e-afeto-conversa-com-mariana-valente/. Acesso em: 13 December 2025.

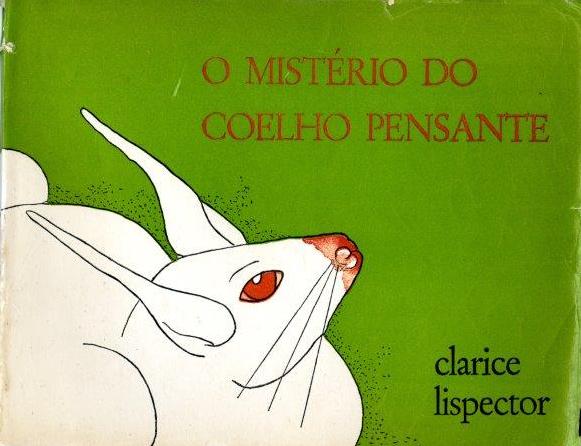

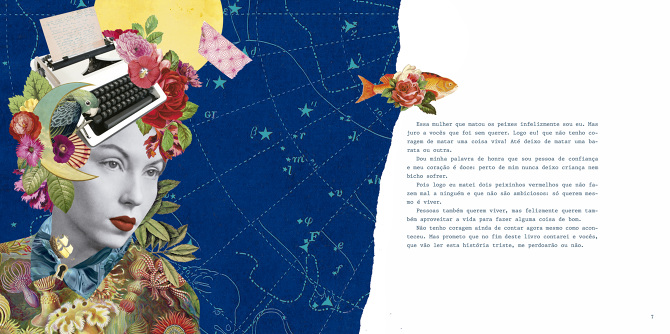

Starting next May, the shelves of Brazilian bookstores will display copies of A mulher que matou os peixes (“The Woman Who Killed the Fish”) with a new look. Published originally in 1968 by Sabiá, the second children’s book Clarice Lispector published during her lifetime will feature a reproduction of the dedication the author wrote for her children, Pedro and Paulo, and for her unborn grandchildren.

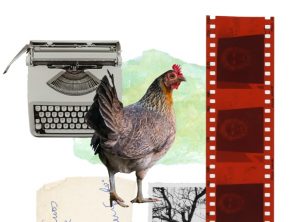

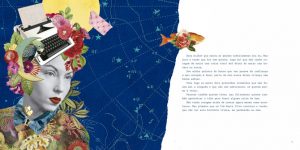

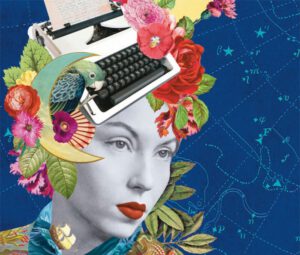

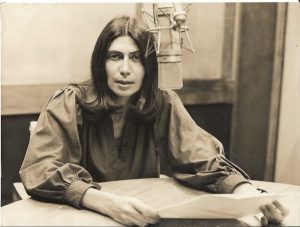

In this new edition from Rocco, our attention is drawn, above all, to the curious illustrations made from affective collages, “nostalgic materials that are relics laden with history and affect,” signed by, of all people, Mariana Valente, artist, native Rio de Janeiro designer, and Clarice’s granddaughter, who spoke with us here at the blog.

You have been working for some time on new editions of Clarice’s work for Rocco, such as As palavras (2013) and O tempo (2014), and are preparing A mulher que matou os peixes. For you, how is this approach and proximity to Clarice’s work?

It’s very curious how I resisted for a few years before diving alone into the beautiful abyss that is to read Clarice. I tried The Passion According to G.H. when I was fifteen, but the warning at the beginning of the book made me rethink and realize that I was far from being someone who was fully formed. I understood that I should wait a bit more. I also read Family Ties in school, for a Portuguese exam, and I was a bit detested by friends in the class who didn’t really understand what they had read well enough to manage the exam. Thus my first contact with the work of my grandmother was a little traumatic. But I started to watch some excellent plays in honor of Clarice, and I felt an enormous urgency to get to know this woman who was so close to me and yet at the same time so distant and mysterious. That was when I read An Apprenticeship at 16 and stopped resisting. Then came Água Viva, and from then on there was no turning back. One cannot likely read Clarice and be the same person as before reading her. The moment I chose (by then I was already an adult) to take up Passion According to G.H. again was very much a revelation for me. One of the most painful and lovely subjective experiences I have ever had. I feel like she helped me to grow through her books. This in particular was a motif for much investigation in therapy! I have more difficulty doing a project that involves my grandmother, because I get very emotional and become fragile, and I feel an enormous responsibility to find a way to translate her work graphically.

Still within the scope of literature and collage production, last year the renowned Portuguese chinaware brand Vista Alegre launched a tureen and special edition of A paixão segundo G.H. (The Passion According to G.H.), both illustrated by you. Recently, at the end of 2016 there was also the exhibition Lendas de Clarice (Clarice’s Legends) inspired by the book Doze lendas brasileiras – como nasceram as estrelas (How the Stars were Born: Twelve Brazilian Legends). Is there a difference among working with the production of objects, exhibitions, and graphic projects?

I think the biggest difference is the medium in which the work takes place, but the process for any new project is more or less the same. If I already have an idea of what I want to do, I go in search of the material (manual or digital), select the images, and then comes the cutting and fitting process. I always photograph this part of the process, because it helps me to see the gaps and flaws to correct. The last phase is to glue and join the parts together. But normally the Clarice splices take more time.

And with regard to your work process, how does it function? What’s the relation between text and image, memory and affect?

In the same way that the writing and reading of Clarice’s texts is done in an almost experimental way, in a stream of consciousness and in the raw, the work with collage also has a similar effect on those who do it and those who observe it. The whole process is very symbolic, and I try to resignify the image in the image itself, much as Clarice resignifies the word in the word itself.

This brings us to our fourth question: Mariana Valente as a reader of Clarice Lispector and Mariana Valente as a granddaughter of Clarice Lispector. Are there boundaries between them? Which came first?

The granddaughter, no doubt. When I was younger and someone found out that I was Clarice’s granddaughter, the person would be emotionally moved and I didn’t understand. I didn’t know her personally but it seemed that everyone who read her knew her deeply. Thus I suspected that reading her work would be very revealing. Like it was, and like it is.

See also

by Bruno Cosentino

by Bruno Cosentino

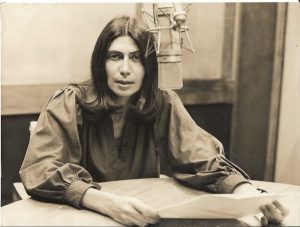

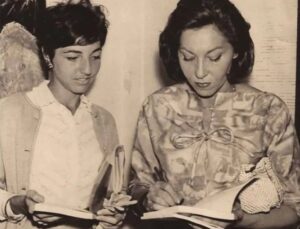

The writer Ana Maria Machado had an unusual and emotional episode with Clarice Lispector. This happened in 1975. After having read an article by Ana Maria, published that very day in the Jornal do Brasil, about the birthday of the writer Roland Barthes, Clarice, who did not know her personally, insistently asked her for help to organize what in two years would be the book The Hour of the Star.

by Elizama Almeida

by Elizama Almeida

It’s the end of 1943. A publishing house of little cultural relevance, A Noite, releases the exceptional Near to the Wild Heart, a book by a 22-year-old author and former employee of the publisher.

by Marina Colasanti

by Marina Colasanti

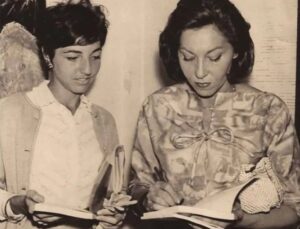

The day I met Clarice was not the same day she met me. I was all adoration, observing her. She had no reason to even lay eyes on me. Leaving the Jornal do Brasil newsroom together, the journalist Yllen Kerr, a great friend of mine, said he was going to visit Clarice and asked if I wanted to go. Did I ever!

by Carlos Mendes de Sousa

by Carlos Mendes de Sousa

Today is Sunday in New York. In fulgent Brasília, it is already Tuesday. Brasília simply skips Monday.

by Equipe IMS

by Equipe IMS

In this video lesson, Mell Brites, author of the book As Crianças de Clarice: Narrativas da Infância e Outras Revelações (The Children of Clarice: Narratives of Childhood and Other Revelations), addresses the theme of childhood in Clarice Lispector’s literature, both in her children's books and in those aimed at an adult audience.

by Manya Millen

by Manya Millen

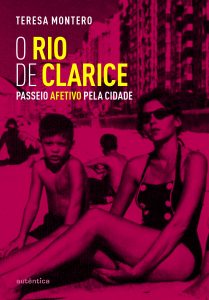

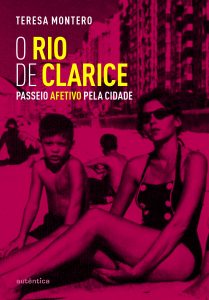

In the book Rio de Clarice, the author's pleasure in wandering the streets, forests, parks, and beaches of Rio de Janeiro, where she arrived as a 15-year-old, is evident.