, Conversion through hatred. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2019. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2019/12/04/a-conversao-pelo-odio/. Acesso em: 01 March 2026.

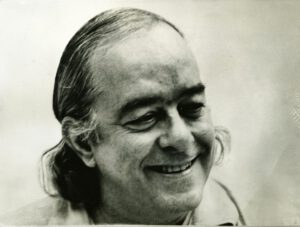

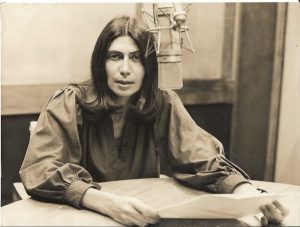

Caetano Veloso says that when he played his song “Odeio” (I hate), which would be included on the Cê album, for his friend and composer Jorge Mautner, while still at his guitar the latter cried and told him that it was the most beautiful love song that he had ever heard. The refrain, which repeats “I hate you, I hate you, I hate you, I hate,” when sung in a low voice, suggests a feeling of gentleness instead of the expected aggressiveness: “it seems sweet,” he explains. Caetano himself declared that when he composed “Odeio,” he was in fact thinking about how love and hate can easily be converted into each other: “when you have a love fight, you get very angry,” he commented in an interview for Rolling Stone magazine at the time of the album’s release, in 2012.

Based on this observation, it is possible to think of an axis in which love and hate are located at two extremes of a single affective mobilization. In other words, hate is love that recedes, despite being equally radical in its passion, while indifference is its opposite. Caetano’s refrain takes advantage of this ambivalence by synthesizing in just one verse — “I hate you” — both the anger of hatred (in words) and the sweetness of love (expressed in the melody and in the “grain” of the singer’s voice). The effect, according to the composer, is to be able “to express love as ‘I hate.’”

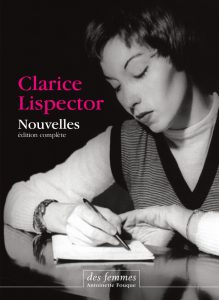

This is the theme of the short story “The Buffalo,” by Clarice Lispector, whom Caetano has been reading since adolescence, when the writer’s first texts were published in the Senhor magazine. The story, included in the book Family Ties, begins inadvertently, as if the facts were already in progress: “But it was spring. Even the lion licked the lioness’s smooth forehead.” Little by little, we find out that the protagonist had been to the Zoological Gardens to learn with the animals how to hate, and she intended to kill. About the motive for the unusual mission, there are two vague and sparse indications in the text. The first, when the narrator briefly describes the submissive posture of the woman before her boyfriend or husband: “everything was caught in her chest. In her chest that knew only how to give up, knew only how to beg forgiveness […].” The second, in a quick flashback, when she finally gathers the courage to tell him that she hated him – “‘I hate you’, she said in a rush;” however, “she didn’t even know how you were supposed to do it. How did you dig in the earth until locating the black water?”

The couple’s fight unleashed the woman’s murderous impetus. Did she go to vent tyrannically at the animals the contained anger to which she was unable to give free reign in her amorous relationship? We also do not know why she believes that the lesson of hatred could be learned from the animals. Is it because they only have instinct? Whatever the reason, she goes from cage to cage and, at each attempt, gets frustrated: the lions licked each other and loved each other exhaustively; the giraffe, like whatever is “large and nimble and guiltless,” was foolish and innocent; the “moist hippopotamus” conveyed a “humble love in remaining just flesh;” in the monkey cage, a mother breastfed her child and an old monkey with cataracts stared at her sweetly – the woman, upset, looks away and escapes. The bestiary continues with the sweet elephant whose strength is overwhelming but not crushing; the patient camel with “dusty eyelashes,” and the coati with a childish and questioning gaze.

Until the spiral guard rail makes the woman lose her center; one no longer knows whether she is outside or inside the cages. She then trades places with the animal and goes from subject to object: “Her forehead was pressed against the bars so firmly that for an instant it looked like she was the caged one and a free coati was examining her.” In concert with animal behavior, the movement of nature only inspired in her notions of freedom and offering: “everything being born, everything flowing downstream;” “out of pure weeds sprouted between the tracks in a light green so dizzying […].” All around, everything therefore opposed her desire for revenge.

Dissatisfied, she walks aimlessly. She then realizes that she is in the amusement park of the Zoological Gardens, in line for the rollercoaster, behind a few couples. Her turn arrives and she sits by herself. The ordinary situation sets off an unsuspected relation with Christian morality: “she looked like she was sitting in a Church.” As the train departs, the character undergoes a physically liberating and sensorially vertiginous experience (which is formally accompanied, in the text, by the sequence of coordinate clauses that list, with repetitions, reminiscences, screams, and situations):

[…] but all of the sudden came that lurch of the guts, that halting of the heart caught by surprise in midair, that fright, the triumphant fury with which her seat hurtled her into the nothing and immediately swept her up like a rag doll, skirts flying, the deep resentment with which she became mechanical, her body automatically joyful – the girlfriends’ shrieks! – her gaze wounded by that great surprise, that offense, ‘they were having their way with her,’ that great offense – the girlfriends’ shrieks! – the enormous bewilderment at finding herself spasmodically frolicking, they were having their way with her, her pure whiteness suddenly exposed.

While riding on the rollercoaster, she becomes mechanical like the machine; she becomes depersonalized. And she loses her reference to the ground. On this aspect, it is worth mentioning a comment by the Italian writer Giulio Carlo Argan, in his book Storia dell’arte come storia della città (History of art as history of the city). By criticizing the obsession of architects and urbanists for a city of the future built so that life occurred on elevated surfaces, he observes that the relation of people with space and each other presupposes ground level as a humanistic reference. It is only based on a common plane, he argues, that all people, in the act of spinning on their own axis, can locate themselves, simultaneously, at the center of the world and periphery of their fellow human beings, who for their part are also centers of themselves and peripheries of others.

The character’s dehumanization provoked by the experience on the rollercoaster can likewise be understood through the dilacerations of the body – “that lurch of the guts.” The fragmentation of the image of the human body – characteristic of vanguard movements from the beginning of the 20th century, such as Cubism and Surrealism – is an expression of denial of the elevated view of the human in favor of a low materialism that accepts the obscure forces of nature. That is what Georges Bataille qualified as “evil,” in the well-known book Literature and Evil, that is, the idea of an unmeasured life that is ideally intense and that therefore must be lived in the transgression of goodness and the morality associated with its conservation.

Not by chance, at the end of the violent experience on the rollercoaster – which totally exposed her! –, the character comes back down to earth and to the humanistic morality of the ground. Pale, “weak and disgraced,” as if she had been “kicked out of a Church,” she “straightened out her skirts primly,” without looking at anyone, like a pariah. Something remains, however, that ferments within her: “the sky was spinning in her empty stomach; the earth, rising and falling before her eyes, remained distant for a few moments, the earth that is always so troublesome.” It is precisely on the troublesome earth – to which she stretches her hands like a “crippled beggar” (still mutilated, therefore) – that she will continue, transformed by evil and by her lesson of hatred alongside the animals. Finally, the link between love and hate is revealed:

Then, born from her womb, it rose again, beseeching, in a swelling wave, that urge to kill […] it wasn’t hatred yet, for the time being just a tormented urge to hate like a desire, the promise of cruel blossoming, a torment like love, the urge to hate promising itself sacred blood and triumph, the spurned female had become spiritualized through her great hope. But where, where to find the animal that would teach her to have her own hatred? the hatred that was hers by right but that lay excruciatingly out of reach? where could she learn to hate so as not to die of love?

In the hyper-morality achieved by the character, love and hate are equal in intensity and become inseparable. Until then, she only knew how to bear, “have the sweetness of unhappiness.” The hatred for which she so longed was the same that served as raw material for her forgiveness. Between sudden bursts of activity and torpor – which demonstrated her disorientation – she rests her hot face on the cold and rusty iron bar of the railings. The temperature shock and the textures provoke in her the sensation of being hated. There is a symbolic rebirth – “opened her eyes slowly,” “a certain peace at last,” “of someone who had just died.”

Finally, she arrives at the cage of the black buffalo. She fixes her gaze on it – the animal stares back. Attentive to the slightest movements of that “a body blackened with tranquil rage,” she realizes that she is being noticed and becomes absorbed. A “white thing” spreads within her – a substance that is similar to the vital “white mass” eaten by G.H. and expelled from the cockroach like ripened fruit from the horror, in the book The Passion According to G.H. “Death droned in her ears” like an enticing breath of evil – a metaphor for living a life of risk. From then on, the character reaches a sort of primordial purity. With her face “covered in deathly whiteness,” she painfully feels the “first trickle of black blood” flow within her: hatred, at last. The buffalo has its back turned to her. She grabs a rock on the ground and tosses it inside the cage. It turns around and faces her, motionless. That is when the woman declares her sentence:

I love you, she then said with hatred to the man whose great unpunishable crime was not wanting her. I hate you, she said beseeching the buffalo’s love.

The character’s search comes to an end in a paroxysm: not the unconditional, “pure love,” of nature, which brings to life “weeds sprouted between the tracks in a light green,” but the love among people who, to become fully realized, requires its opposite: hatred – according to Freud, the basic human affect, from which love is erected as a construct. Hatred is also the basis of the political theory of Thomas Hobbes, in the Leviathan, when he defines sovereignty. According to his maxim, man, wolf to men, fears violent death, and for that reason, the self-preservation instinct, subsidized by hatred of the other, establishes the regulatory state of collective life. Self-love adds rigor to the relation among equals. However, it is before the buffalo – in a sort of bullfighting ceremony –, and not anyone else, that the character feels threatened and threatening, “trapped in this mutual murder.” This is the moment in which hatred arises as a self-defense impulse and she feels anger at what could destroy her. Here we discover the reason why the lesson on hatred was sought at the Zoological Gardens. If one cannot call hatred that which in animals is merely instinct, it is in the so-called animal instinct of man that hatred resides. And that is how the short story ends: the woman falls on the ground in slow vertigo. One does not know if she dies or faints. But was not death – whether real or metaphorical – the North Star of this love story?

*Image of the title page taken from the book Death in the Afternoon, by Ernest Hemingway. Unidentified author.