, "Love Smells Like Death". IMS Clarice Lispector, 2019. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2019/07/23/o-amor-tem-cheiro-de-morte/. Acesso em: 13 December 2025.

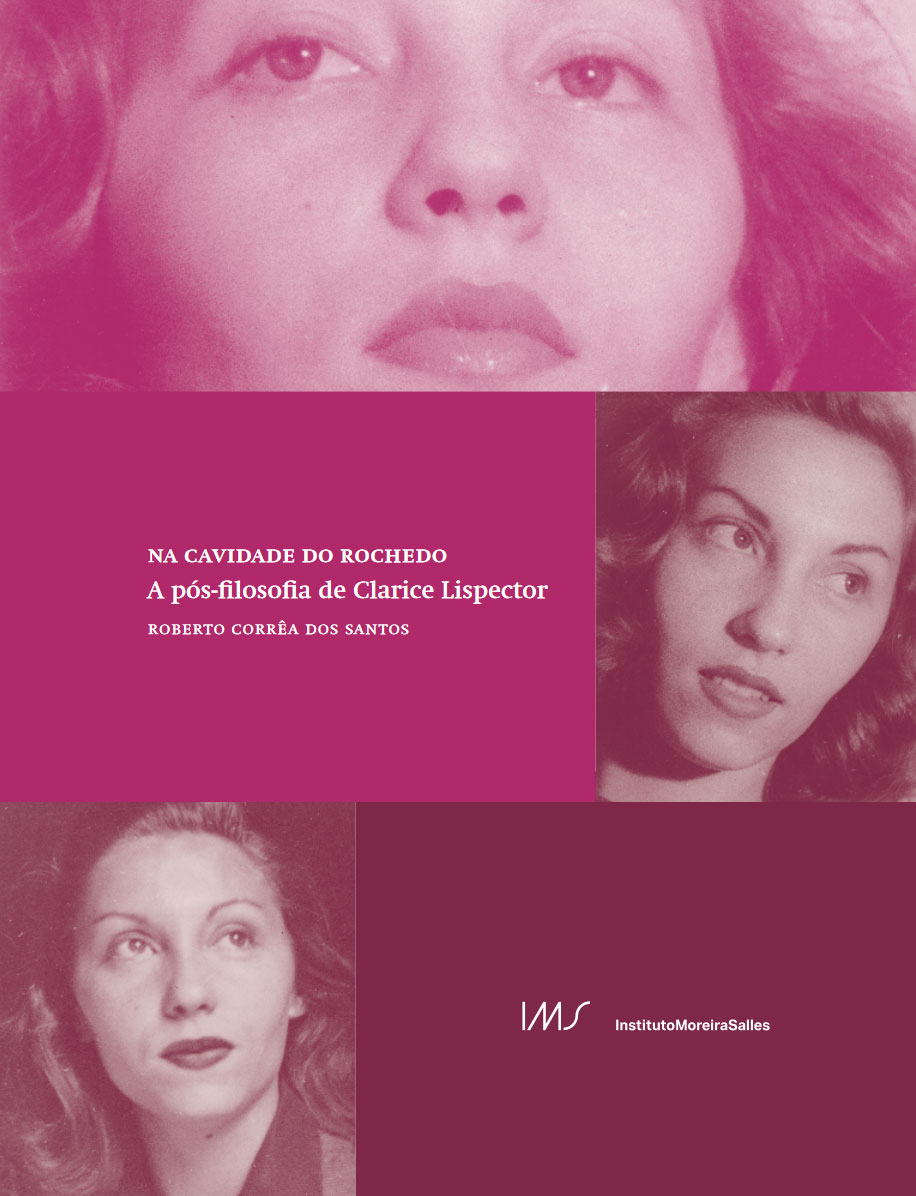

Clarice Lispector wrote about sex only once. It was in the book A via crúcis do corpo (The Via Crucis of the Body). Even so, as her biographer Benjamin Moser observes, “the theme that unites the collection is not, in fact, sex. It is motherhood.” Indeed, based on this comment, it is possible to think that the writer undoes the boundary line that separates maternal love and sexual desire by uniting the two instincts into a conjunction, such as in the female organ common to birth and to copulation.

Moser also says that some of the writer’s friends considered her “touchingly naive” in matters of sex. Her friend and plastic artist Maria Bonomi, who at the time had separated from her husband to date a woman, was supposedly interrogated with “technical questions” by a curious Clarice. Such an interest was also imprinted in the article “O vício impune da literatura” (The unpunished vice of literature), published in the Folha de S.Paulo, in 1992, in which one reads about a supposed “exchange of imported pornographic magazines” between her and the poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade.

In any case, it is Clarice herself who is evasive, in the preface to A via crúcis do corpo: “if there’s indecency in the stories, it’s not my fault. Needless to say it didn’t happen to me.” In 1975, in an interview given to the Manchete magazine on the occasion of the book’s release, she reiterates: “Even I was surprised […] how I knew so many things about the topic.”

If it is true that there is almost no sex in Clarice’s work, it is also a fact that her literature is impregnated with eroticism; an eroticism that touches the limits of matter. The best example of this is the mystical experience that the main character of The Passion According to G.H. undergoes when she eats the white mass of the dead cockroach that she had just crushed against the closet door, in the maid’s microcosmic room.

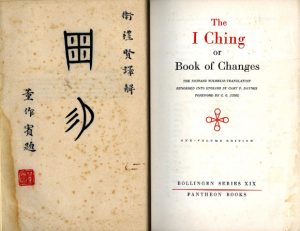

The incident with G.H. can be understood in light of what the French thinker George Bataille, in his book Eroticism, classifies as “sacred eroticism,” which is connected to the concrete world, to its objects, and is therefore distinguished from the eroticism of bodies or of hearts – an experience that is thus independent both of sexual and personal relations.

For him, the depersonalization of the erotic fusion can be considered similar to that experienced in sacrificial rituals. In the face of the immolation of the victim – in the case of G.H., the cockroach –, what is revealed to the senses of the participants, who often eat it, is the experience of the sacred. As Bataille affirms: “a violent death disrupts the creature’s discontinuity; what remains, what the tense onlookers experience in the ensuing silence, is the continuity of all existence with which the victim is now one.”

Continuity and discontinuity are terms that must be understood as the reintegration of a mortal and singular being, who is therefore discontinuous, to the general fermentation of life, which is indistinct and impersonal. As in Lavoisier’s maxim, “nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed,” the body serves as food for bacteria, which participates in the decaying process of human flesh and sets in motion the incessant cycle of life and death.

The immediate horror experienced with the putrefaction of the corpse reveals to men and women the unavoidable affinity between the “stinking putrefaction” of death and the essence of life itself. Thus, if on the one hand “the horror of death drives us off, for we prefer life; on the other an element at once solemn and terrifying fascinates us and disturbs us profoundly.”

A disturbance of such an order, Bataille continues, is triggered by the direct contact with that which is commonly called nausea or repugnance. The term he uses, “sovereign disturbance,” perfectly fits that which critics and Clarice herself call “existential moment,” “surprise,” “flash,” “epiphany,” etc., in her work. The overcoming of disgust seen in sacrifice is the same that, in the face of an unexpected event, will cause the disorder that comes from reality-based erotic experience to burst in Clarice’s characters. It is an experience that, since it is not part of our will, always “waits upon chance,” according to the French thinker.

But if for the writer, as we have seen, sex is not a priority, what is it that is revealed, then, in the blatant eroticism of her texts? In The Passion According to G.H., she herself answers: “Ah, people put the idea of sin in sex. But how innocent and childish that sin is. The real hell is that of love. Love is the experience of a danger of greater sin — it is the experience of the mud and the degradation and the worst joy.”

In the short story “Love,” from the book Family Ties, Clarice Lispector narrates the story of Ana, a housewife who is on the tram, tired, returning from the market to her house, and carelessly thinking about everyday life at home: the broken stove, her children, her husband – to everything, Ana gave “her small, strong hand, her stream of life,” one reads.

The narrator warns the reader: “A certain hour of the afternoon was more dangerous. […] when the house was empty and needed nothing more from her, the sun high, the family members scattered to their duties.” At this moment, Ana became restless. Before having a family, her life was “restless exaltation,” it was no longer within reach, for she “had created at last something comprehensible, an adult life” — in order.

Absorbed in her thoughts, Ana is disoriented, all of a sudden, by the sight of a blind man chewing gum: “[…] her heart beat violently, at intervals. Leaning forward, she stared intently at the blind man, the way we stare at things that don’t see us. He was chewing gum in the dark. Without suffering, eyes open. The chewing motion made it look like he was smiling and then suddenly not smiling, smiling and not smiling — as if he had insulted her.”

It is worth observing the original way that Clarice stages some clichés, restoring to them the original meaning of the words. The trivial description of the blind man – eyes open in the dark, which is equivalent to the commonplace “seeing in darkness” – is metaphorically figured as a sort of existential longing on the part of the character: the calm understanding of life in full ebullition, in its intrinsic disorder. The chewing that seemed to make him oscillate between laughter and seriousness evokes, in the same way, the reconciliation “without suffering” between opposites, in a unity that is primordial and “inexpressive,” as G.H. says.

Suddenly, the tram brakes and the bags that were on Ana’s lap fall on the ground. She yells. The driver stops. She collects what was scattered on the ground. But the eggs had broken: “viscous, yellow yolks dripped through the mesh” of the knit bag. Here, we witness the representation of yet another catch phrase: “the life that slips through your fingers.” The yoke, the egg of a chicken, if fertilized by the male, gives life; if not, it is life that could have been and was not. Thus, once the spoil of life – her own? – has been discarded, all the fragile harmony of Ana’s everyday life also slips away.

She then perceives an absence of law; she no longer knows where to go – “She had pacified life so well, taken such care for it not to explode. […] And a blind man chewing gum was shattering it all to pieces.” Without realizing it, she missed the stop for her house and, in a rage, gets off the tram. It was getting dark. Little by little, she recognizes the place where she is and walks through the Botanical Garden. Equivalences arise with the Garden of Eden, which, on the one hand shifts the Judeo-Christian mythical paradise to the real park in the city of Rio de Janeiro, but, on the other, describes it in new terms. Contrary to the nice and lovely atmosphere in Genesis, in “Love,” horror and degradation are established:

There was a secret labor underway in the Garden that she was starting to perceive. In the trees the fruits were black, sweet like honey. On the ground were dried pits full of circumvolutions, like little rotting brains. The bench was stained with purple juices. With intense gentleness the waters murmured. Clinging to a tree trunk were the luxuriant limbs of a spider. […] it was a world to sink one’s teeth into […]. it was fascinating, the woman was nauseated, and it was fascinating.

Bataille, in another text, the essay “The Language of Flowers,” published in the magazine Documents in 1929, criticizes the image of the flower as a symbol of the discovery of love. The frequent association would be explained, according to him, by the fact that both the brilliance of flowers and human feelings are “a question of phenomena that precede fertilization.” Nevertheless, for men and women, what becomes a sign of desire, in the flower, is the corolla, its most decorative aspect, and not the sexual organ, a “rather sordid tuft,” covered by the petals. The flower’s appearance is equivalent, therefore, to an ideal of human beauty and, for this reason, says nothing about its real nature – flowers “wither like old and overly made-up dowagers, and they die ridiculously on stems that seemed to carry them to the clouds,” affirms the thinker, for whom “love smells like death.”

To destroy the impression of harmony in the nature of plants, Bataille continues, it is enough to imagine “the impossible and fantastic vision of roots swarming under the surface of the soil, nauseating and naked like vermin.” To roots, in contrast to stems, could then be attributed the lowest moral value. The similarities between Clarice’s text and Bataille’s arguments are evident (and somewhat unprecedented). She writes: “The erotic impulse of entrails is linked to the eroticism of the twisted roots of trees. It is the rooted force of desire. My truculence. Monstrous viscera and hot lava of burning mud.” [1] The theme reappears in The Passion According to G.H.: “the unclean is the root — for there are created things that never decorated themselves.”

In “Love,” Ana’s experience is therefore the experience of interdiction. The narrator alerts the reader: “The moral of the Garden was something else.” Unlike the biblical garden, where God already dictated orders to the first couple, in Ana’s garden (or Clarice’s), it is the character herself who encounters, without prescription, and with a mix of attraction and repulsion, the erotic depersonalization that reconciles good and evil in an indistinct and amoral totality. In the words of Spinoza, of whom Clarice was an enthusiastic reader, Ana allows herself to be “affected” by the things of the world and learns an ethical lesson that has the body as a seat and real experience as a base. In a manner very close to the Dutch philosopher, Clarice reflects, in The Passion According to G.H., upon morality:

Would it be simplistic to think the moral problem with regard to others consists in behaving as one ought to, and the moral problem with regards to oneself is managing to feel what one ought to? Am I moral to the extent that I do what I should, and feel as I should? All of a sudden the moral question seemed to me not only overwhelming, but extremely petty. The moral problem, in order for us to adjust to it, should be at once less demanding and greater. Since as an ideal it is both small and unattainable. Small, if one attains it: unattainable, because it cannot even be attained. […] The solution had to be secret. The ethics of the moral is keeping it secret. Freedom is a secret.

The Secret (or The Ethics)

Ana was breathing in the putrid perfume of the decomposing plants – until she remembers her children. She immediately feels guilty. But why? “What was she ashamed of?” When she left the garden, she was no longer the same. Now, “her heart had filled with the worst desire to live.” And this was incompatible with her previous routine. Still in a trance, she arrives home, receives guests for dinner; the children play in the living room. Everything seemed normal, but she was absent and delirious, and she involuntarily frightens one of her children:

Mama, the boy called. She held him away from her, looked at that face, her heart cringed. Don’t let Mama forget you, she told him. As soon as the child felt her embrace loosen, he broke free and fled to the bedroom door, looking at her from greater safety. It was the worst look she had ever received. The blood rushed to her face, warming it.

Ana’s senses were saturated and the atmosphere of the house was like an overwhelming shadow. She hears an explosion on the stove. “What happened?!”, she asks her husband, startled. He becomes surprised by his wife’s fear; “‘It was nothing,’ he said, I’m just clumsy.’” He brings her close to him and caresses her. Ana transfers to her husband all the love of one who had come face to face with death and tells him in a serious tone: “I don’t want anything to happen to you, ever!” He finds what she said funny; “Time for bed,” he says. He then leads his wife to bed, “removing her from the danger of living”; back to the night that follows the day that follows the night – practical life, which, although miserable, nevertheless bears the existence of who knows love.

[1] The passage, written by hand on the backside of the typescript for “Objeto gritante” (“Screaming Object,” the text that gave rise to the book Água Viva), is quoted by the Angolan critic Carlos Mendes de Sousa, in Clarice Lispector: pinturas (Clarice Lispector: Paintings).