, In love with love. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2019. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2019/02/05/amar-o-amor/. Acesso em: 19 April 2024.

Before publishing her first book, while still a law student, Clarice Lispector had worked in the press as a reporter and editor for the National Agency and in periodicals such as the magazine Vamos ler! (Let’s Read) and the newspaper A Noite (Night). At the end of the 1960s, already famous, she accepted the invitation to assume an interview section in the celebrated Manchete. For almost a year and a half, important figures from literature, theater, music, visual art, and sports underwent the writer’s question-and-answer sessions, including friends such as Lygia Fagundes Telles, Rubem Braga, Maria Bonomi, and also Vinicius de Moraes.

What immediately calls for attention in the conversations with Clarice is a sort of unsuitableness for the job with respect to journalistic technique: she is too personal, she is at times indiscrete, and the worst of heresies, she talks about herself as if she were being interviewed. It could not have been any different, and of course, the magazine knew it – the session would be called “Possible Dialogues with Clarice Lispector.” Instead of possible, it would perhaps be better to say improbable.

In the interview with Vinicius, published in 1969, the first approach immediately sounds like a provocation: “Vinicius, did you ever really love someone in life?” Now, in theory, that was no question to ask, even more so without warning, to the famous lover of women and great proponent of love lyric in Brazil, author of sonnets that are monuments of the Portuguese language and correspond to those of Camões in importance.

The writer explains that she had telephoned one of the poet’s ex-wives, who had told her that when he is in love he gives his all: to children, women, friendships. That is why Clarice arrived at the idea that what Vinicius really loved was love, and women were included in it. “It’s true that I love love,” he answered, “but that doesn’t mean I didn’t love the women I had. I have the impression that, to those I really loved, I gave my all.”

Clarice, certainly because she knew the biography of the poet, about to marry for the seventh time, proceeds: “I believe you, Vinicius. I really do. Although I also believe that when a man and a woman are in true love, the union is always renewed, no matter what the fights and disagreements are: two people are never permanently the same and this can create new loves in the same pair.”

A beautiful reflection on love, however totally in contrast with that of the poet, who argues: “Of course, but I still think that the love which lasts for eternity is passion-love, the most precarious, the most dangerous, certainly the most painful. That love is the only one which is as big as the universe.”

The interviewer retakes the floor, undismayed: “Do you break up because you meet another woman or because you get tired of the first?”

In my life it’s as if one woman had placed me in the arms of another. Maybe because this passion-love is unable to survive due to its own intensity. I think this is expressed aptly in the final couplet of my “Sonnet of Fidelity:” “Be not immortal since it is flame/ But be infinite while it lasts.”

The interview continues, but for the meantime let us stop here. With such direct and disconcerting questions, Clarice intuitively touches sensitive points of the amorous personality of Vinicius. Passion-love is one of them. According to the philosopher Alain Badiou [1], romantic love highlights the initial ecstasy of the first encounter, which would not be, for him, the most important moment in an amorous relationship. Such a love is based, rather, on a lasting construction, to which he also gives the name of “stubborn adventure.” Thus, unlike the apprehension of the instant as the only temporal dimension of eternity, he proposes a conception that is “less miraculous and more hard work, namely a construction of eternity within time, of the experience of the Two, point by point.”

Clarice would agree with Badiou. For Vinicius, however, love should be experienced in paroxysm: “but to love is to suffer, but to love is to die of pain,” he sings in one of his Afro-sambas, “Canto de Xangô,” in partnership with Baden Powell. The poet wishes to merge with his loved one, but the acute awareness of misfortune causes him suffering. Going into the heart’s reasons of which reason itself is unaware, he seeks to make the impossible possible in the rebirth of love in new relationships. The opposite of Clarice’s approach, to create new loves in the same relationship.

Thus would come the feeling that, for the author of “Sonnet of Fidelity,” his life was as if one woman had placed him in the arms of another. That is also why, in his verses, there is often the analogy between real women and the imagined ideal woman, such that the former assumed the qualities of the latter. No poem better exemplifies such a fusion than “Epitalâmio” (Epithalamium). In this poem, at the end of a long list of women’s names – some of which antithetically reinforce archetypal qualities (Shadow / Dawn, Vandal / Saint, Lofty / Smooth), and others that evoke supposedly real women (Alice, Maria, Nina, Linda, Marina, Maja, Clélia) with whom he had some type of amorous experience – the poet is astonished:

Vejo chegar alguém que me procura

Alguém à porta, alguma desgraçada

Que se perdeu, a voz no telefone

Que não sei de quem é, a com que moro

E a que morreu… Quem és, responde!

És tu a mesma em todas renovada?

Sou Eu! Sou Eu! Sou Eu! Sou Eu! Sou Eu!

(I see someone arrive looking for me

Someone at the door, some wretch

Who is lost, the voice on the telephone

That I do not recognize, the one I live with

And the one who died… Who are you, answer me!

Is that you, the same in all of them, renewed?

It’s me! It’s me! It’s me! It’s me! It’s me!)

The “Sou eu!” (It’s me) that emphatically echoes in the last verse of the poem introduces a revealing ambiguity, for it can mean both the answer of a woman and the actual voice of the poet, who is confused with her or even with all of them – in this case, the polyphony would come from as many voices as the women evoked. It is an answer that combines in a single phrase poet, real women, and the ideal woman (“a mesma em todas renovada” [“the same in all them, renewed”]) and it performs in the poem, therefore, the fusion with the loved one that is impossible in real life.

For the poet, the love devoted to women was the most important way to plenitude in love. But it is not the only way. In his first answer to Clarice, he affirms: “I understand this love to be the sum of all loves, that is, the love of a man for a woman, a woman for a man, the love of a woman for a woman, the love of a man for a man, the love of a human being for the community of his or her fellow human beings.” The conversation between them continues, but all of a sudden, they grow quiet.

Vinicius breaks the silence: “I have so much tenderness for your burnt hand….”

It is worth recalling that, three years earlier, Clarice had started a fire in her house after falling asleep with a lit cigarette. With serious burns on her body and on the brink of death, she spent two months hospitalized at the Pio XII Clinic in Rio de Janeiro, from where she left with sequelae, mainly on her right hand.

Moved, the writer addresses the reader and acknowledges: “this man involves a woman with tenderness.”

By touching a painful issue in the life of Clarice, the poet corresponds to the emotional intensity established by the writer herself at the beginning of the interview. What the delicate observation by Vinicius reveals here is the amorous game in which both were entangled – for both, love and pain are inseparable feelings.

A sort of diffused seduction involves the two. Clarice asks Vinicius for a poem. He improvises a precise and impressive portrait of the author of The Passion According to G.H. He reaches the center of her obsession, the incessant search for the “self” in its immanence, and, in the objective condition of Other (as a mirror), he subjectively returns to her the singularity of existence, concentrated in the couplet formed by her own name. He thus says: “You write one word above and the other below because it’s a verse:”

Clarice

Lispector

“I think your name is beautiful, Clarice,” he says in praise.

The interview is over, but the writer wishes for further verification; she telephones one of the poet’s ex-wives and asks her: “How do you feel married to Vinicius?” She answers: “Very good. He gives me a lot. And more importantly, he helps me to live, to get to know life, to like people.” She also talks to an “intelligent girl:” “Would you go out with him?” “No (…) I love another man. And Vinicius reveals to me, moreover, that I love that man. His music makes us enjoy love even more. And ‘suddenly, no more than suddenly,’ it becomes something else (…).”

The epilogue ends up revealing the unavoidable ethical unfolding of Vinicius’ work, which is impregnated with life and at all times overcome by a contagious effect that transforms other lives. These lives, for their part, will not follow his model, but his courage to live.

Clarice ends by saying: “Because there is greatness in Vinicius de Moraes.”

[1] In the book In Praise of Love (2009)

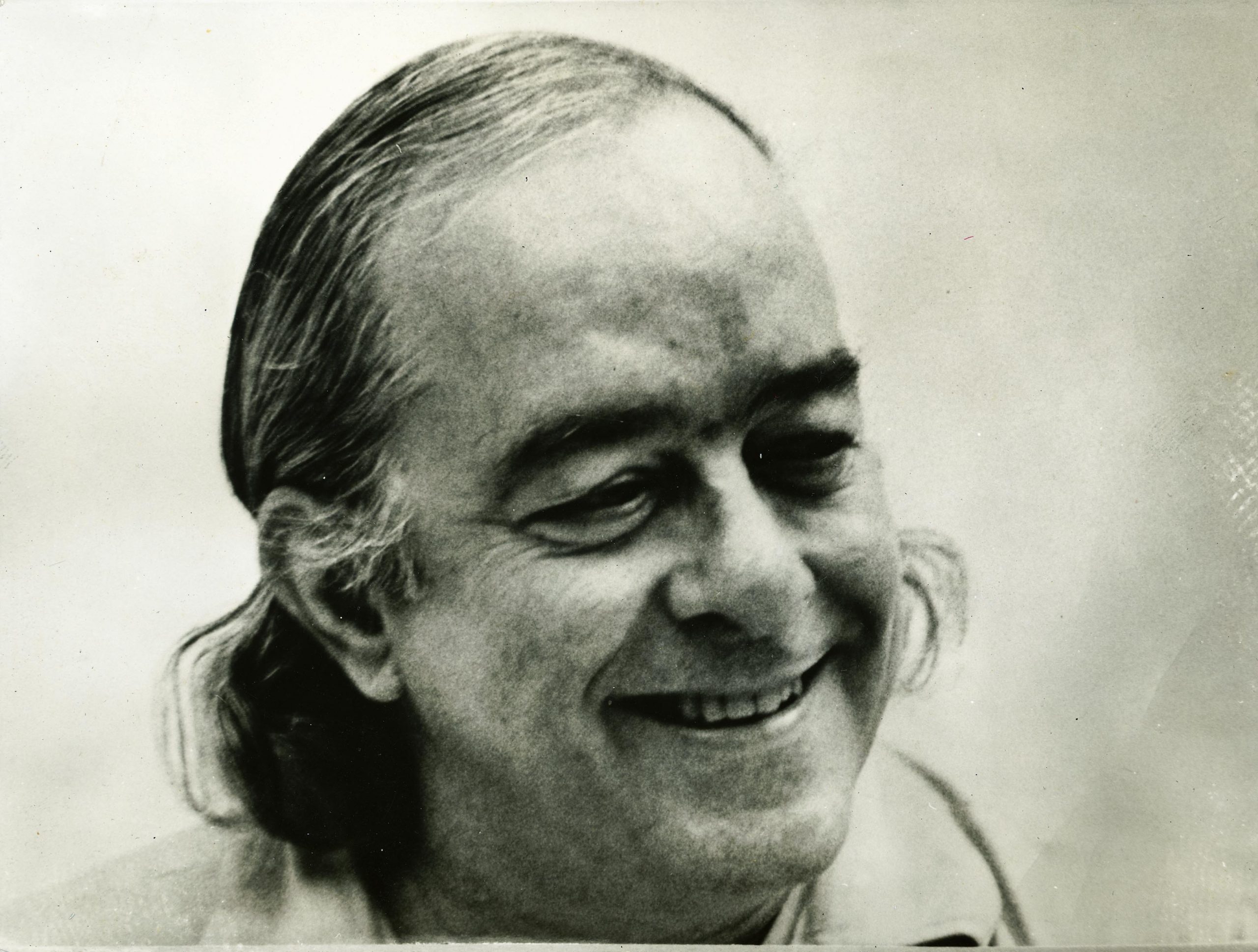

*Highlighted photo: Vinicius de Moraes, 1971. By Alécio de Andrade. Pirelli/MASP Photography Collection.

**Bruno Cosentino is a singer and songwriter. He has released the albums Amarelo (2015), Babies (2016), Corpos são feitos pra encaixar e depois morrer (2017) and Bad Bahia (2020). He is the editor of the music criticism magazine Polivox and a PhD in Brazilian literature at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), with research about love and eroticism in the poetry and songs of Vinicius de Moraes.