, Clarice Lispector in the lineage of Machado de Assis. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2017. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2017/08/14/clarice-lispector-da-linhagem-de-machado-de-assis/. Acesso em: 26 July 2024.

When it comes to the topic of Brazilian crônicas (which are often more like short stories than chronicles), one instantly thinks of the name of Rubem Braga as a primary representative. “The greatest chronicler,” according to Clarice Lispector.

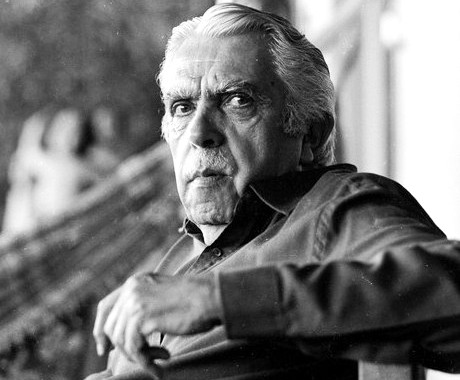

The writer from Espírito Santo, who modestly considered himself a typewriter that is “a little used, but still in good condition,” had a new collection recently published with texts gathered in book form for the first time. In O poeta e outras crônicas de literatura e vida (The poet and other chronicles of literature and life), edited by Gustavo Henrique Tuna, the old Braga, who used to write every day, uniquely registers certain profiles of intellectuals who were already well-known at the time: Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Manuel Bandeira, Joel Silveira, Rodrigo de Melo Franco, Aníbal Machado, and of course, Clarice Lispector.

On December 11, 1965 in Manchete, the second most important weekly news magazine during its heyday, Rubem Braga dedicated his column to Clarice Lispector. In that year, Clarice published the third edition of Family Ties, a collection of short stories released by Editora Francisco Alves in 1960 for which the author would receive the Jabuti Prize for literature. His diagnosis of the Ukrainian-born writer from Pernambuco was as simple as it was daring. According to Braga, Clarice would come from the same lineage as Machado de Assis.

Up next, one of the 25 chronicles that make up the volume of chronicles by Rubem Braga.

Clarice Lispector, a Carioca Storyteller

This brief information from Petit Larousse about Virginia Woolf is very French: “Romancière anglaise, née à Londres (1882-1941); sa finesse rappelle la manière du romancier français Marcel Proust.”[1]

It would be possible to say that Clarice Lispector’s finesse recalls that of Virginia Woolf – which actually seems to be her strongest influence. But what most surprises and captivates me in Clarice’s short stories, such as those in this admirable volume Family Ties, which is now in its 3rd edition, is the strong Carioca flavor in this writer who has lived so many years abroad. As introspective as the writer may be, she not only is alert to the turmoil and confusion of the soul, but is also especially sensitive to the lights, the sounds, the winds, and the temperature, to details of the landscape and the environment.

Her characters are not only from Rio de Janeiro, they are from certain streets, certain neighborhoods, and bear this trademark: at the Copacabana meal “the daughter-in-law from Olaria showed up in navy blue, glittering with “pailletés” and draping that camouflaged her ungirdled belly;” and she remains the whole time as if she were blocked off in her spiritual refuge of Olaria, staring challengingly at her husband’s sister-in-law from Ipanema.

The lazy and raunchy Portuguese girl could only live on Riachuelo street and dine with white wine at the Tiradentes plaza. The lady of “The Imitation of the Rose,” this girl who was “was a brunette as she obscurely believed a wife ought to be,” is basically a Girl from Tijuca. And Rio lives in this book, with is botanical garden and its zoological garden, its old streetcars, its heat, its quiet nights, its suburban flower gardens, its flies, its Saturdays and families.

What I’m saying is only marginalia for Clarice’s book, which is most interesting because of the intense internal vibration of its beings, and its mastery of style and composition, which none in Brazil can surpass. But for all of us who live in Rio, and who for the first time have vaguely become Carioca patriots after the capital moved to Brasília, it is sweet to feel the city gasp and shake over the heads of these creatures, as if it wanted to capture and condition them.

And in this year of the Quadra-Centennial, we proudly and gladly feel that the Ukrainian-born Pernambuco writer Clarice Lispector is actually a great Carioca storyteller, in the good and noble lineage of Machado de Assis.Manchete, December 11, 1965

O poeta e outras crônicas de literatura e vida

Rubem Braga/Global Editora, 102 pages

Ed. Gustavo Henrique Tuna

[1] A British novelist, born in London (1882-1941). Her finesse recalls that of the French novelist Marcel Proust.