, Matryoshka: two or three words on a travel notebook. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2017. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2017/06/29/matriosca-duas-ou-tres-palavras-sobre-um-caderno-de-viagem/. Acesso em: 05 March 2026.

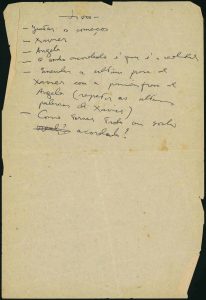

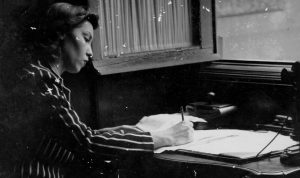

Penworthy: thin notebook, fits in the palm of the hand, 17cm x 10.5cm and 58 pages. On the cover in cursive handwriting, and apparently with some pride, there is the name she assumed after being married: Clarice Gurgel Valente. As of January 23, 1943, Clarice Lispector would sign her name this way, full-time wife of the diplomat Maury Gurgel Valente who, that year, was appointed to serve as vice consul in Naples. The spouse will cross oceans right in the middle of the war to meet him in Italy. The trip lasts from July 19 to August 24, that is, more than a month in transit, in a state of travel, of expectation, of longing, of restlessness, and of anxiety. Tania, my dear sister, I love you.

It is her first international trip, straight to the unknown. Countries, people, marital status, the future unknown. Excited thoughts, through her eyes everything is new, everything is new, everything is – what goes through the body that it is not possible to share with the other? “What others are to the ascetic in a community, the notebook is to the recluse,” teaches Foucault. One writes, therefore, to relieve thought.

Coming to light in 2012 (prior to this it was under the care of the principal heir), the travel notebook is quite unique compared to the documents already known to researchers, editors and readers.

Penworthy overlaps different times. Sitting somewhere in Liberia, July 31, 1944, late at night, Clarice describes the experience of that day which she spent in still untouched villages of black people: “With the journalist Ana Kipper, the captain David Crockett, and Bill Young, I went to the black villages, Tallah, Kebbe, Sasstown”. She recalls what she did, what was said, what she saw. The booklet as a platform that keeps things from oblivion.

Liberia, Fisherman’s Lake, July 31, 1944

With the journalist Ana Kipper, the captain David Crockett,8 and Bill Young, I went to the black villages of Tallah, Kebbe, and Sasstown. Black women with bare breasts in villages where missionaries have not arrived. They work for the Americans and speak a little English (in Monrovia there are 24 or 25 dialects). They suddenly say: hello! They love to wave goodbye. I saw a young woman with very beautiful breasts. But most of them, still young, have large and sagging breasts. They are clean and healthy. But some children [14] have navels as big as oranges. A black man, to whom I had said goodbye and given a prolonged smile, on purpose, was enchanted and put his hand on his [erased].9 The young black women paint their faces with cream-colored strokes and their lower lips with a cream-colored paint. One of them asked for my shoes. Another, whose little boy was pleased by me, said: Baby nice, baby cry money. One of the guys gave her a nickel, she said: baby cry big money. One said something long and complicated. I saw that it was about me and she was laughing. (they laugh with great ease, but some are sad and even their laughter is one of humility and fascination.) I ask one of them, who spoke English, what she had said: he tried to summarize, finally saying: that you are fine, she likes you. They asked about my headscarf. I took it off to teach them how to put it on and when they saw my hair, they became serious and attentive.

Until Clarice interrupts the text and returns (returns?). “The missionary is talking about something with Ana Kipper.”- the gerund indicates that while recording the visit to the village, an episode parallel to the narrative and perhaps relevant was happening right there in front of her.

This return is somewhat cruel. How to go back, have dinner, go to the cinema, and move on? How not to turn inside out? Cinema will always be boring, dinner lackluster. This return-no return recalls the story of the character Ana herself, from the short story “Love.” How to return home, to the children, to the husband, to make dinner, after having seen a blind man chewing gum? How to reorganize the room, clean up, after noticing and eating the cockroach? How to be happy dressed in pink at the Recife Carnival if the mother is dying?

Don’t return.

Clarice in that situation, that village of black people, would be just another tourist who would leave some money for the mother of the child who begs for “big money.” That episode for Clarice would be the impulse to compose the short story “The Smallest Woman in the World” (Family Ties, 1960 – “At that moment, Little Flower scratched herself where no one scratches.”), “Africa” (Foreign Legion, 1964) and “Corças negras” [Black Does] (Jornal do Brasil, April 5,1969). That is, twenty years would pass and the Fisherman’s Lake episode would not fail to echo.

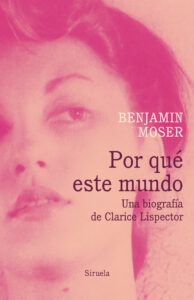

The distance in time, in this case decades, is the right measure to join a biographical episode to a poetic text that serves to expand the fictional text. Biography intimately implicated in production.

Penworthy not only stands out from the other archival documents, but also escapes more technical archival definitions. Notebooks are common, like those of the Minas Gerais poet Paulo Mendes Campos and the study of the Russian language, and other manuscripts or typescripts for literary purposes. The normative classification, however, does not exactly fit the travel notebook. Is it a personal document? Yes, it holds very precise, informative data, accounts, and addresses. Is it an intellectual production? Yes, it holds excerpts that would be used in novels, short stories, and chronicles. Is it a planner? Yes, it contains dates, times, phone numbers, and appointments.

According to Louys Hay, there are two types of notebooks: diaries and work instruments. While the first are made up of notes whose referential space and temporality are defined by the clock and the calendar, the latter are dedicated almost exclusively to linguistic studies and experiments, the elaboration of phrases, titles, essays, and a list of proper names.

Although in the world of words no classification has an absolute value, Penworthy has both attributes, but it is a third type. This notebook would seem to be a composite, a genre that mixes the ephemeral and the essential, everyday events and literary projects, fragments of forms or ideas.

There are, in these writings, which have not yet passed, and will not pass, through the knife’s blade of the other – and this other can be the reader, the public, or the market -, there are energy expenditures in these hand gestures that do not correspond to any apprehended model. It may be a gain for the field of literature studies to think of this material not from the point of view of a certain curiosity regarding the erasure or which word the author has omitted – a very common approach to genetic criticism.

It may be a gain for the field of literature studies to think that a notebook retains the agitations of the body.

And to ask what language is that which serves both the author and the woman, the tourist, the wife of a diplomat? What language is this, the only possible and familiar presence in the face of an unknown world – Liberia, Portugal, Italy? How many folds can language make in the service of such and such a situation? The vernacular choreography in which an extremely utilitarian language and literary language converge on the same page?

A thousand folds. Matryoshka.

Dealing with this type of writing – that of writing in notebooks – means raising it to the category of a text that dialogues with experiences and events without repressing the documentary value and status of a literature that is inscribed there.

It is precisely in this writing medium, in this thin notebook, without, at first glance, robust literary content and disengaged from existing archival categories, that one finds a fundamental reading of not only geographical displacements, but, above all, of literary and personal displacements.

The notebook was described and its contents are available for reading here.