Bingemer, Maria Clara. Between Mystery and Politics. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2021. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2021/07/08/between-mystery-and-politics/. Acesso em: 13 December 2025.

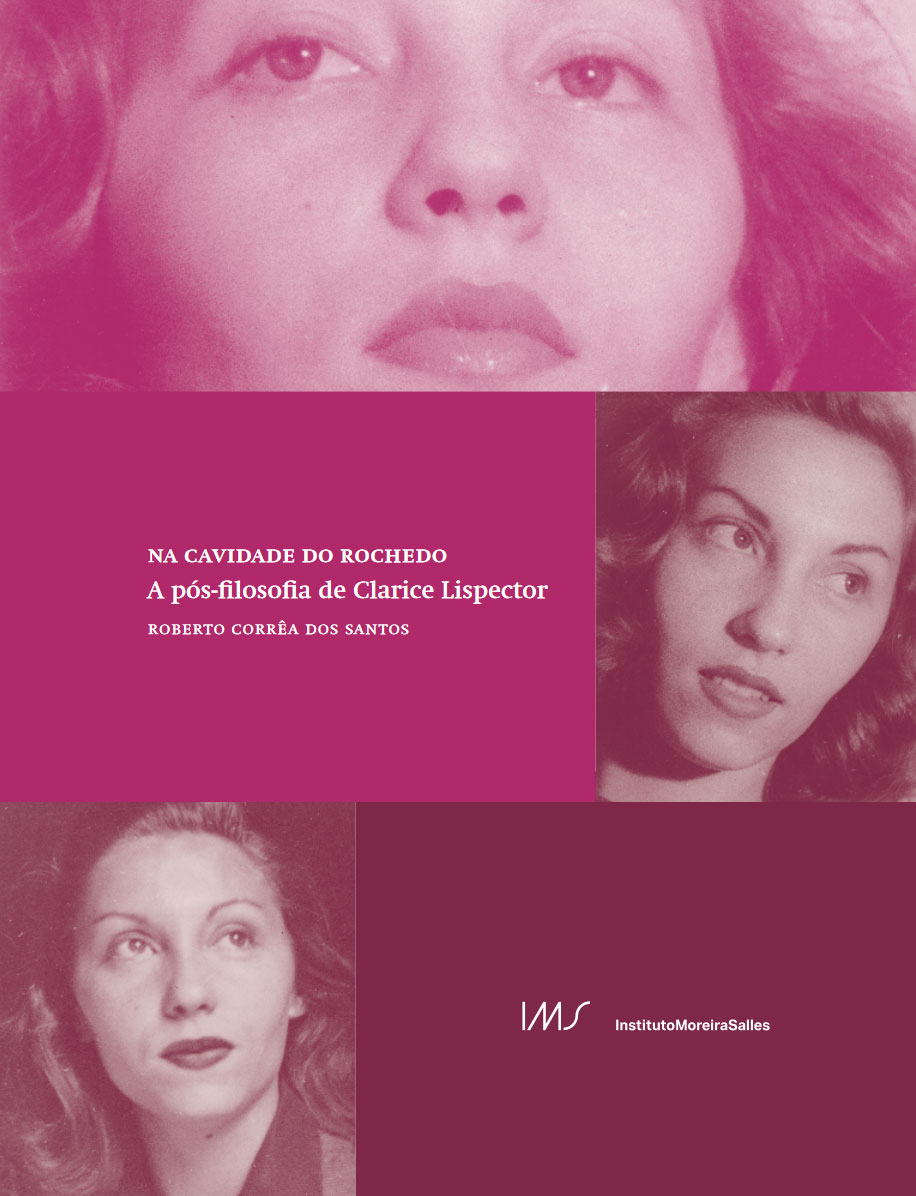

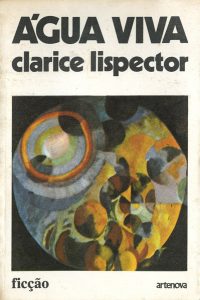

The numerous commentators who not only in Brazil but also throughout the world investigate Clarice Lispector’s work encounter several aspects to highlight in her multifaceted writing.1 From the fruitful tension between transcendence and contingence to the profound and refined attention to the human condition, one can encounter an immense variety of dimensions in her body of writings. There is, however, an aspect of Clarice’s texts that is – it seems to us – less observed. It concerns the social and political sensitivity of the writer. And because it seems to us extremely important, we will dwell precisely on this.

Clarice reveals in her texts – novels, chronicles, or short stories – a true openness to the other and its difference and, above all, its vulnerability. Even characters like GH, a wealthy bourgeois woman, will learn to commune with the whole in her maid’s room. But in a special way, Clarice’s gaze will dwell on and identify with the northeastern girl Macabéa, whose cavity-ridden body and life of “less” lead her by the hand in the narrative at the same time that they question her crudely. This last novel, so to speak, “rescues” this feature of writing in a prophetic and explicit manner.

It is she herself who says in one of her chronicles, “Literature and justice:” “Ever since I have come to know myself, the social problem has been more important to me than any other issue: in Recife the black shanty towns were the first truth that I encountered.” Always inhabited by the thirst for justice, Clarice declares that this is a constitutive feature of her identity, a feeling so obvious and basic that it cannot surprise her. And that is also why she cannot write about it, since for her it never concerned a search, but a confirmation of something existing in herself.

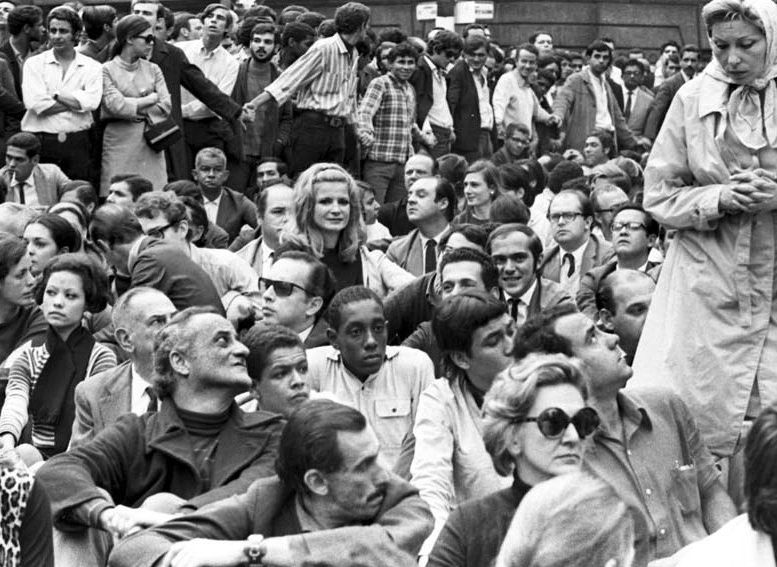

At the same time, the conscious and lucid writer is amazed by the fact that this obviousness which inhabits her does not occur with the same obviousness to all of her peers. As Silviano Santiago affirms, “the more the Jewish immigrant adapts and conforms to the new national frame, the more indignant and pessimist she becomes with regard to the world as presented to her.” Injustice is something that she internally abhors, and Clarice openly declares so on several occasions. She even takes concrete actions against this injustice, such as, for example going to the March of the One Hundred Thousand, participating in clandestine political gatherings, etc. Silviano Santiago calls this attitude “participant indignation, declaring it to be a matter of survival in a society under military dictatorship and a state of exception.

Clarice’s perspective on injustice and evil is personalized. It considers a person and from him or her it arrives at the collective that he or she represents. This is how the narrator of The Hour of the Star captures the desperate gaze of a northeastern girl in the middle of the crowd.2 And this gaze brings him discomfort and compassion, as he compares the girl’s situation to his own, living in abundance and comfort and realizing that the northeastern woman represents the majority of the population in the country where she lives.3 That is how Macabéa is born, from the writing of the narrator who is Clarice Lispector’s character, but who is also Clarice herself, whose gaze captures the suffering and pain of others, the fruit of injustice, and deposits them in her book. From there, the narrator shapes Macabéa’s body, which is oppressed by poverty and sadness. He confesses his discomfort and difficulty in undertaking this adventure of narrating Macabéa: “With this story I’m going to sensitize myself, and I am well aware that each day is a day stolen from death. I am not an intellectual, I write with my body.”4 And he adds: “If I know almost everything about Macabéa it’s because I once caught the eye of a jaundiced northeastern girl. That glance gave me every inch of her.”

Macabéa only has weaknesses and subtractions in her life. She is a woman, she is a northeastern migrant alone in the big city, she is a virgin, innocuous, dreary, ugly. The narrator describes her “slumped shoulders like those of a darning-woman,” with a “cavity-ridden body.” She was “a fluke. A fetus tossed in the trash in a newspaper.” Writing about her causes discomfort, since the writing is heavy with brutality. “I promise you that if I could I would make things better. I’m well aware that saying the typist has a body full of holes is more brutal than any bad word.”

The narrator actually sees in the humiliated poverty of the northeastern girl something incomprehensible, greater than herself. The girl’s helplessness makes Clarice approach a profound mystery: “Why should I write about a young girl whose poverty isn’t even adorned? Maybe because within her there’s a seclusion and also because in the poverty of body and spirit I touch holiness, I who want to feel the breath of my beyond. To be more than I am, since I am so little.” This poverty that diminishes, that oppresses, that belittles, is imagined by the narrator to perhaps be a choice on the part of Macabéa herself and therefore the source of her infinite dignity: “Maybe the northeastern girl had already concluded that life is extremely uncomfortable, a soul that doesn’t quite fit into the body, even a flimsy soul like hers… Because, no matter how bad her situation, she didn’t want to be deprived of herself, she wanted to be herself… So she protected herself from death by living less, consuming so little of her life that she’d never run out.” This deadly “savings” is more painful for Clarice than anything else in her character, since it constitutes a brutal denunciation of the injustice that victimizes the northeastern girl.

The narrator confesses how difficult it was to make his character die. And this occurs because, touching her poverty in body and soul, he feels that he has touched holiness, the virgin core of the human condition that has nothing of his own, nothing upon which to draw and is destined for contempt, oppression, and humiliation until the end of her life. That is why he describes her hit-and-run (a term he uses in place of death) like this: “She lay helpless on the side of the street, perhaps taking a break from all these emotions, and saw among the stones lining the gutter the wisps of grass green as the most tender human hope.” And the feeling of dying is one of exaltation and not of despair: “Today, she thought, today is the first day of my life: I was born.”

Death is what finally makes Macabéa into a star, like the movie stars she so admired. In death she received the kiss, the definitive embrace. And above all, she rested from the painful and useless effort to live. The last word that comes out of her mouth is “future.”

Among the cobblestones and passersby, her struck body agonizes. And the narrator –Clarice, actually – sees the pain of this poor girl as an epiphany. “She’d gone to seek in the very deep and black core of her self the breath of life that God gives us.” Macabéa, just like all those who day by day seek life in the midst of oppression and injustice, now receives the embrace of death as a joy. “Then — lying there — she had a moist and supreme happiness, since she had been born for the embrace of death. Death which is my favorite character in this story.” She wishes for life and knows that only death will give it to her. Hearing Macabéa say her last word, “future,” the narrator asks himself: “Would she have longed for the future?”

Life triumphs in Macabéa, about whose death the narrator exclaims: “Yes, that’s how I wanted to announce that — that Macabéa died. The Prince of Darkness won. Finally the coronation.” The cavity-ridden body was now a luminous, transfigured body. The hour of the star had sounded and Macabéa shone upon the darkness that could not swallow her.

The narrator, humiliated in his conscience, confirms that he was actually the one who died. Macabéa – now “free of herself and of us” – killed him. Clarice’s social sensitivity, her political conscience, sees in the diminished life of the northeastern girl the grim work of the injustice that plagues the country that is her own. And because she cannot do away with it, she writes. She prophetically denounces the poverty that is a mystery of suffering and holiness of the victims who every day experience death as the only thing that will one day finally free them from the life that they did not choose but are condemned to live.

It is symptomatic and eloquent that Clarice’s last novel, The Hour of the Star, is so clearly marked by her gaze to the margin, to the northeastern girl who incarnates the marginality of poverty and of contempt. Gazing at Macabéa and her life of “less,” the writer dies from her alienation and is transformed, learning to be aware of her privileges and of the oppression of the poor who constitute the overwhelming majority of the population in the country where she lives.

The writer’s “participant indignation” occurs when she looks and sees a body without a place to be, a body that is hardly comfortable in life, a body that does not find a meaning and whose plenitude only occurs in death. In this star that is dark on the outside and suddenly bright on the inside, which has neither grace nor beauty to attract the eye, which is like hair in soup that turns the stomach and spoils the appetite, is the secret, the mystery of life and of its Creator that has always fascinated and challenged the Jewish Clarice Lispector.

Notes

1 Translated from the Portuguese by Marco Alexandre de Oliveira.

2 About The Hour of the Star, see our article “Via Crucis e gozo pascal,” in Geraldo de Mori and Virginia Buarque (Eds.) Escritas de ser no corpo, SP, Loyola, 2017, p. 105-122.

3 The Hour of the Star, op. cit., p. 15: “Because on a street in Rio de Janeiro I glimpsed in the air the feeling of perdition on the face of a northeastern girl.”

4 This quote and all others belong to the book The Hour of the Star.