, Conversation with José Castello. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2018. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2018/05/02/conversa-com-jose-castello/. Acesso em: 01 March 2026.

The critic José Castello will teach new classes for Grupo Clarice, a group dedicated to the reading and study of the works of Clarice Lispector. Among the works discussed are Água Viva and The Passion According to G.H., in addition to the texts recently collected in the Complete Stories edition and the chronicles that comprise the book Discovering the world. The next meetings will take place on May 11th and 12th and July 20th and 21st at the Instituto Estação das Letras (IEL). Below is a brief email conversation with José Castello:

What kind of public is attracted to Clarice’s texts?

What impresses me most in the Clarice groups is the almost total predominance of lay readers. Of course, writers and literature teachers also tend to participate. But the majority of students are lawyers, psychologists, journalists, doctors, psychoanalysts, etc. I have even had physicists, astronomers, dancers, architects, and mathematicians in my groups. What does that say? Although she was a very cultured woman, in her books Clarice works above all with existence. She herself didn’t like to be called a writer, she considered herself just an ordinary woman. This intense openness to life and the real appears with much force in her writing. And it attracts all kinds of readers.

How do you view the reception of Clarice’s oeuvre in Brazil, and the author’s recent success in the United States and Europe?

I believe that in Brazil we still have, in general, a fairly distorted image and view of Clarice’s work. Distorted by prejudice (because she was a very beautiful woman, who in this view perhaps should have been on television, or in the beauty salons, but not in literature), and by intellectual laziness (many don’t even give her a serious reading and then fix on a quick impression of her). There’s even a certain disdain that Brazilian readers themselves hold towards Brazilian literature. Some simply say that Clarice didn’t create literature, but philosophy, or was merely an author of aphorisms, hastily sewn together, or even that she was a witch, and not a writer. Some even see her as a mere author of catchphrases and generic thoughts, in the style of a Madame de Sévigné. But Clarice isn’t just a writer, she’s an uncommon writer. I think she is on the level of a Kafka, or a Pessoa. Now that the translation market has expanded, it’s natural that the world is discovering her. Even if slowly, often viewing her with great suspicion or distrust, still they are discovering her.

What seduces you most about the writer’s work?

I am, in particular, touched by her immense courage. Clarice writes exactly what she thinks. For this reason, her writings are often frightening: because they bring us a frontal and unadorned view of reality. A reading of Clarice – if we read for real, without prejudice and defenseless – always shakes us. When I read for the first time, at 18 years old, The Passion According to G.H., I quite simply got sick. I had a high fever and immense weakness that no physician could explain. One day, an old family doctor, after examining me, declared: “This is only passionitus.” What a great literary critic this doctor was! Without even knowing it, he simply read The Passion According to G.H. in my body.

What is the current status of Clarice Lispector?

We live in hard and dogmatic times. The time of beliefs and convictions, dominated by pragmatism and the idea of practical results. Clarice goes against the current of all that. She had a libertarian spirit, she was not attached to anything, and she wouldn’t allow anything to hold her back. She was also a woman very touched by the concrete problems of her time. The devastation caused by hunger, for example, appears in many of her writings. For those who still insist on seeing her as a frivolous woman, a rich housewife – and how many still think that way! –, it’s enough to recall, for example, that in 1968 Clarice was in the first row of the historic March of the One Hundred Thousand in Rio de Janeiro. Life and the present are her great themes. I think her literature attracts us so much for this reason.

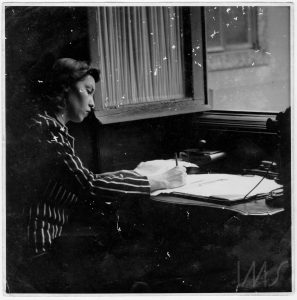

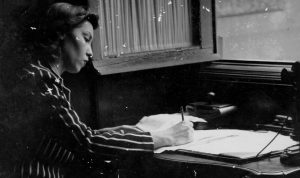

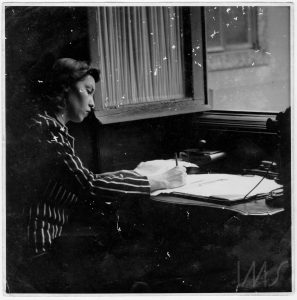

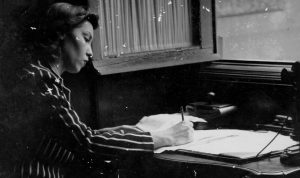

*Photo: Miller of Washington/ Clarice Lispector Collection/ IMS

See also

by Elizama Almeida

by Elizama Almeida

Every year the University of Tennessee prepares AuthorFest, a series of activities to celebrate the work of a single author. In its second edition, AuthorFest paid tribute to Clarice Lispector.

by Elizama Almeida

by Elizama Almeida

Ulysses was Clarice Lispector’s last dog, a mongrel who stole cigarette butts and queued for Coca-Cola and whiskey for visitors. He was so eccentric that he earned a robust note in the infamous periodical O Pasquim.

by Bruno Cosentino

by Bruno Cosentino

Clarice Lispector will be honored at the Brazil booth at the 44th Buenos Aires International Book Fair, which will take place between April 24 and May 14.

by Elizama Almeida

by Elizama Almeida

One of Clarice Lispector’s most translated books, The Hour of the Star was published almost 40 years ago by José Olympio in October of 1977.

by Augusto Ferraz

by Augusto Ferraz

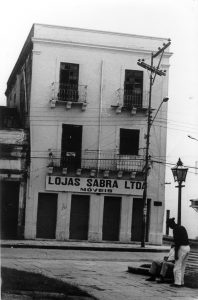

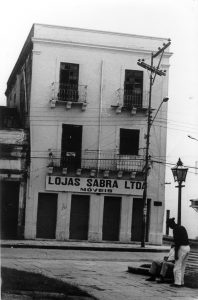

I died. I found out when, one day, on the sidewalk of Praça Maciel Pinheiro, I lifted my head, opened my eyes, and saw myself dead, there on the plaza’s sidewalk, the two-story house on the other side of the street. My broken heart inside my chest, the two-story house on Rua do Aragão, 387, where, on the second floor, Clarice Lispector lived a happy childhood here in Recife, despite the pains of the world and experiencing and feeling, mainly, the pains of an implacable disease that would one day take Mania, her mother, away from her. I found out when, laid out on the sidewalk there under the scorching Sunday sun, I turned my head to the right and saw a man beside me, who was also looking at the house.

by Elizama Almeida

by Elizama Almeida

In partnership with the Department of Humanities at Columbia University, the IMS presents the international seminar The Clarice Factor: Aesthetics, Gender, and Diaspora in Brazil.