, Without Formulas. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2014. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2014/04/28/sem-formulas/. Acesso em: 26 July 2024.

In 1970, Clarice Lispector started to write a work that would come to be called Água viva [translated into English as both Água Viva and Stream of Life].

According to Nádia Gotlib in “Memória seletiva” (Selective Memory), published in a special edition of Cadernos de Literatura Brasileira (Brazilian Literature Notebooks) on Clarice Lispector:Incorporating old notes, she begins to work on a new novel entitled Atrás do pensamento: monólogo com a vida (Behind Thought: A Monologue with Life). The book, which in a later phase would be called Objeto gritante (Screaming Object), would finally be called Água viva and would come out under the broad genre of “fiction,” given the author’s understanding that she had surpassed conventional classifications of literary narrative.

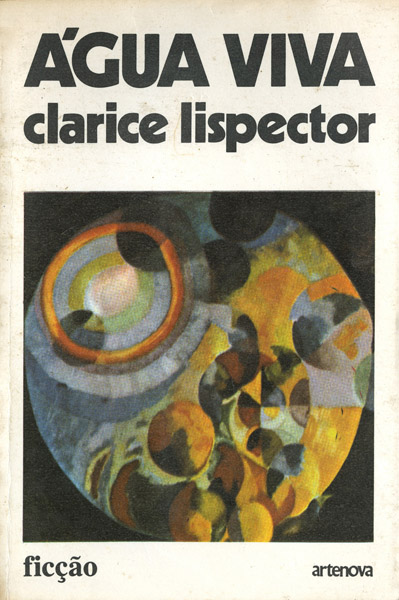

Cover of the 1st edition of Água viva, published in 1973 by Artenova. Ana Cristina César Library/ IMS collection

Professor Clarisse Fukelman analyzes Água viva and says that, in this work, the author “radicalizes innovative writing processes with which she had already experimented in previous publications” and develops a book in which “there is no linear story or central theme.”

Água viva was published at the end of August 1973 by the publisher Artenova. Below is a handwritten excerpt from the work’s manuscript under the care of the Moreira Salles Institute, followed by its transcription.

Excerpt from the manuscript for Água viva, by Clarice Lispector. Clarice Lispector Collection / IMS collection

Calo-me.

Porque não sei qual é o meu segredo. Conta-me o teu, ensina-me sobre o secreto de cada um de nós. Não é segredo difamante. É apenas esse isto: segredo.

E não tem fórmulas.

[I go quiet.

Because I don’t know what my secret is. Tell me yours, teach me about the secrets of every one of us. It’s not a slanderous secret. It’s only this: a secret.

And there are no formulas.]