Ferraz, Eucanaã. A Literature Without Literature. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2021. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2021/08/09/a-literature-without-literature/. Acesso em: 13 December 2025.

The chronicles of Clarice Lispector were collected in a book for the first time in 1984, in The Discovery of the World, a volume edited by Paulo Gurgel Valente, the author’s son, who arranged in chronological order 468 texts published in the Jornal do Brasil between 1967 and 1973. I read and reread those almost eight hundred pages many times, going from beginning to end, then back to the beginning, and I came to leap from one wonder to another. A single page would launch me into an unsettling experience. I returned to those illuminations so many times over the years that, despite my terrible memory for everything, I realized, at a certain point, that I knew several passages and phrases by heart. The new edition, now with the title Todas as crônicas (All the Chronicles), was enough for me to reread again, and once more, all of those texts to which the new editor, Pedro Karp Vasquez, added another 120 theretofore uncollected texts.

But I had discovered Clarice Lispector before The Discovery of the World, when I read Água Viva, a book published in 1973. As a young and beginning reader, I experienced the deep impression of a disturbing work, which was absolutely not a novel, which did not concern poems either, which resembled a diary, though it was not, which was somewhat similar to a philosophical essay, even though its twisted, strange movement sought nothing but to express sensations about writing and artistic creation. And it was not enough to say that it was a bundle of loose notes about the things of the world and about time. Aware of the irresolute and experimental character of the book, the author classified it as “fiction.” It was a way of explaining without explaining, or rather, of escaping from the narrow limits of so-called literary genres. When I first read the texts of The Discovery of the World, I recognized, as if I were dizzy, passages I had read in Água Viva. I do not know if I came to think what seems so clear to me today: that the pages of the Jornal do Brasil, detached from their source, muddled the signs that distinguished book writing from newspaper writing.

Writers are not—and never have been—preoccupied with preserving boundaries between genres. If the chronicle is difficult to circumscribe, describe, or simply approach, the grouping of Todas as crônicas not only does not help to set limits, but also makes any demarcation impossible. If it concerns, on the one hand, the characteristic indeterminacy of the hesitant prose that has long frequented newspapers and magazines, there is, on the other hand, a fluidity that moves beyond that, disturbing perspectives, disorganizing systems, refusing laws.

Intrinsically communicative, factual, ephemeral, light and transparent, the chronicle would be unfeasible for an author whose short stories and novels were defined by a writing opposed to such characteristics. Clarice, however, assumed the task of writing every week without abdicating what publication in mass media demanded of her. The flagrant contradiction, instead of dissolving into an easy and comfortable outcome, ended up engendering a creative process that would display its dilemmas, conflicts, and perplexities to the eyes of the reader. Thus, already in her third week collaborating with the Jornal do Brasil, the chronicler affirmed: “I still feel a little uncomfortable in my new role which cannot be strictly described as that of a columnist. And besides being a novice in the art of writing chronicles, I am also a novice when it comes to writing in order to earn money. I have had some experience as a professional journalist without ever signing my contributions. By signing my name, it automatically becomes more personal. And I somehow feel as if I were selling my soul.”1

Even though the passage consolidates a dilemma mentioned by other authors — the more or less conflicting difference between writing literature, on the one hand, and, on the other, writing for money (for a newspaper) —, the declaration, considered in the set of chronicles, leads to another ponderation, that apart from the easy antagonism there was in the soul of Clarice a more powerful and subterranean unrest: the vague but decisive refusal of literature. With this I mean that by immediately consigning that she was writing “to earn money,” she took another step — a way already cleared — outside the literary institution, a gesture to be understood less as a frivolous circumstance and much more as a rejection in depth, no matter to what extent the writer was aware of it at the moment. Such an attitude, it should be noted, was not limited to the mere demystification of the image of the writer as someone who does not take part in vile and pragmatic matters. The financial injunction would return later, once again displayed uncloudedly, but the assertion now would be above all provocative: “They pay me to write. So I write.”2

Rubem Braga

It is commonplace to consider the chronicle a minor genre, despite its virtues and the excellence of its practitioners. Clarice did not aggrandize it. Let us say that, on the contrary, she diminished herself to its size and made a point of making clear the course that she was taking. Furthermore, if she did not intend to elevate the genre, she exercised it in a process of vehement diminishment, as if she were seeking to shrink the genre until making it disappear. We read at a certain point: “To be frank, this can scarcely be called a column. It is simply what it is. It does not correspond to any genre. Genre no longer interests me. What interests me is mystery.”3

Therefore, instead of refusing the trademarks that define the secondary character of the chronicle — those that distance it from literature, or even from everything that, under such a code word, is considered major —, Clarice, at first, adopted the characteristic features of the genre seeking to adjust to it, but soon began to activate them, finding in this operation a freedom as extreme as it was risky, which certainly gave it the real dimension of writing something so minor that it was no longer literature or anything else except writing—just that, beyond all classification.

In this sense, “The Case of the Gold Fountain-Pen” is exemplary, bringing into play an allegory that ironizes the demand for a major writing: “are the words written with a gold pen also made of gold? Would I be obliged to write more elaborate sentences because my implement was so much more precious? And would I end up writing in a completely different style? And if my style were to change, surely that would have the effect of changing me as well. But in what way? For the better? And there was another problem: what would happen if I were to find, like King Midas, that everything I wrote with my gold pen turned out to have the brilliance and unyielding hardness of gold?”4

It is easy to see how much Clarice discovered in the chronicle a complete way to escape from the “brilliance and unyielding hardness” demanded of literature. But the escape was not a program to be executed in an unreflective way, for if the chronicle seems, by nature, to permit the escape from literary gilding, it does not fail to offer its models, artifices, and genre traits, albeit minor. Dissonantly, the new chronicler readily probed her suspicions and indecisions. She shed light, for example, on obstacles that sounded insurmountable: “I want to speak without speaking, if possible.”5

Chronologically accompanying the many uncertainties, we distinguish the fluctuation of a subjectivity that is expressed by acceptance and reception, but also by constant doubt, to the point of exasperation: “The Jornal do Brasil is making me popular. I get roses. One day I’ll stop. To become transformed.” And, further on: “I know that what I write here cannot be called a chronicle or a column or an article. But I know that today it’s a scream. A scream! I’m tired!”6

The enthusiastic response from the readers lent her some security, to which was added a lively contentment, to the point that, remaining foreign to the métier, to the extent that she wrote something which she could not name except as “a kind of chronicle,” she designates herself as a columnist and chronicler, and even though she does not understand the mystery of being one of them, she feels like one of them: “I’m a happy columnist. I wrote nine books that made many people love me from a distance. But being a chronicler has a mystery that I don’t understand: it’s that chroniclers, at least those from Rio, are much loved. And writing the kind of chronicle on Saturdays has brought me even more love. I feel so close to whoever reads me.”7

However, the favorable, loving reception of the readers did not eliminate other suspicions. Furthermore, the public’s love somehow fostered uncertainties, generating a spiral of inquiries about the act of writing and about the indecipherable bonds that unite work, author, and reader, inquiries expressed with astonishment one moment and with tranquility the next, which endured as a nerve, either implicit or explicit, in those texts. As for being a chronicler, certainty and indecision went hand in hand: “I know that I’m not, but I’ve been meditating a bit on the matter.” And furthermore: “Actually, I should talk to Rubem Braga about it, since he invented the chronicle. But I want to see if I can fumble my way through the matter alone and see if I come to understand it.”8 Here are manifested both the desire of the beginner who yearns to adapt to the genre and the appetite of the apprentice for discovering her own solutions, one of which is the unusual and constant exposure of her voluntary isolation and of her confrontation with the craft.

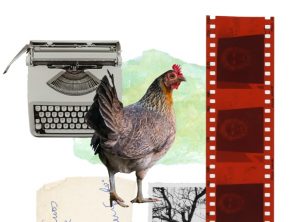

At the Typewriter’s Pace

The collection of chronicles recomposes the weekly dialogue with the readers as a continuous speech, for whom the “columnist” frankly unveiled not only anxiety and confusion, but also the joy of maintaining a loving closeness. Often the anguish seemed overcome and the writing was resolved beyond literary expectations: “As you all can see this is not a column, it’s just conversation.”9 If the problem of genre — compliance with certain standards — would be overcome by an exception attained within the genre itself, another resistance persisted: the exposure of intimacy. This time, Rubem Braga was actually summoned to rescue the author, who declared: “Memorandum: one day I telephoned Rubem Braga, the master of the so-called crônica, and confided in despair: ‘Rubem, I am no columnist, and what I am writing for the newspaper is becoming exceedingly personal. What am I to do?’ He assured me: ‘When you are writing chronicles it is impossible not to get personal.’ But I do not want to tell anyone about my life: my life is rich in experience and vivid emotions, but I never intend to publish an autobiography.”10

The judgment pronounced by the master did not placate the restlessness, which would be mentioned many times: “I have noted something extremely disagreeable. These articles I write for my weekly column are not exactly chronicles, in my opinion. I am beginning, however, to understand our greatest chroniclers. Because they sign their work, they ultimately reveal themselves. Up to a certain point we are able to know them intimately and to recognize their style. And personally I think this is a good thing. When I write my books, I remain anonymous and discreet.”11

The poignant difference between book writing and newspaper writing consisted, therefore, in the propensity for a kind of nakedness that was irrepressible in texts that demanded periodicity. Another quote is in order: “in writing a weekly column I am allowing readers to know me. Am I in danger of losing my privacy? What am I to do? I type out my articles at the typewriter’s pace, and when I look to see what I have written, I realize I have revealed something about myself. I even believe that if I were to write an article about the over-production of coffee in Brazil, I should end up sounding personal. Am I in danger of becoming popular? The thought horrifies me. I must see if anything can be done to remedy the situation. Words by Fernando Pessoa which I read somewhere give me some reassurance: ‘To speak is the simplest way of becoming unknown.’”12

The good-humored hypothesis — humor is a decisive feature of Clarice’s chronicles — of an objective writing (her approach to the “problem of the overproduction of coffee in Brazil”) reveals an unrealizable zero degree of writing, that is, the author’s inability to remain shielded in impersonality, which, finally, coincides with Rubem Braga’s lesson. Thus, what is the reason for the permanent discomfort with the observation that in the “column” the person of the writer was made known? And what is the full scope of the affirmation that she did not want to tell anyone about her life and that she never intended “to publish an autobiography?”

By saying she was “anonymous and discreet” in her books, Clarice transferred to the chronicle the entire load of intimacy and biographism, as if she were being driven by an uncontrollable force. And, interestingly enough, her strength seems to come from outside her. Not from a higher, mystical, or divine force, but from something quite prosaic: her typewriter. Thus, both her non-compliance with literary principles and her manifestation of intimacy emerge through the force of a mechanism whose performance in time is capable of defining her creative process — speed would determine writing, and the chronicler, more than once, guarantees that she writes “at the typewriter’s pace.”

One of the most important critics of Clarice Lispector’s work, the Portuguese academic Carlos Mendes de Sousa, observes in Figuras da escrita (Figures of Writing; Instituto Moreira Salles, 2012) that Clarice’s novels originate from a slow pace, since they are operated by the slow machine of rewriting or from compositional effort, while the chronicles arise from a fast machine, conducive to the flow and to the association of ideas. In the latter case, the free and quick transit of sensations prevails, which often abruptly incorporate metalinguistic awareness: “Ah, this is neither a chronicle nor a column, I know. For once I don’t think it matters: the days go by, the typewriter goes on. But if I were a chronicler, ah, I would not lack topics!”13

The paraphrase is irresistible: there is a direct relationship between text and time; between the pace of days and the pace of the typewriter; between writing driven by the time of the typewriter, and of days, and not being a chronicler; between not being a chronicler and not having anything to say. Everything takes place as if the typewriter determined the transit of writing, and this, then, escaped the control of the author, who, at certain moments, seems to be watching what takes place from the outside, surprising herself and recording her estrangement. “The charlatan sells himself short. What was I about to say?”14

The mechanism becomes apparent here at the moment when the quick flow — without being interrupted — incorporates self-awareness. Something similar occurs in the following fragment: “My God, how love stops death! I don’t know what I mean by that: I believe in my incomprehension, which has given me an instinctive life, while so-called comprehension is so limited.”15 Sometimes, the awareness of the speed seems to interrupt the flow: “I’m writing very easily, and very fluently. I cannot trust that.”16 This record of mistrust and of the apparent interruption of the march may not be exactly a brake, but a moment of deceleration.

Even complaining about the loss of her “privacy,” Clarice accepted that writing “at the typewriter’s pace” exposed her, and she even came to want that, although she refused what she deemed autobiographical. It is necessary to consider the gravity and, at the same time, the irony of the following statement: “I’m sorry to say, I’m a mystery to myself.”17 If there is a strong autobiographical dimension in Clarice’s chronicles, it is necessary to pay attention to another order of values that is insistently staged: she did not fully know about what she was writing, since she sought the unknown in what was most banal, as if she found everything and everyone and above all herself strange; she also did not know how she wrote, surrendering to the “typewriter’s pace;” finally, she understood even less what she wrote—chronicles? a “kind of chronicle?” articles? conversations? What would Clarice be biographizing, after all? The only answer, which will seem oblique for being too direct, would be: ignorance. Or even: mystery.

Instinct

There is no autobiographical project, or a stable issuing center, and this becomes clearer when the chronicles transcribe other people’s speech or texts, often letters from her readers. More important, however, is the impression that emerges from the whole, that these hundreds of pages are a collection of unstable fragments, sudden flashes, remnants. When I used the expression “continuous speech” here, I was referring to the permanence of Clarice Lispector’s dialogue with her readers, which does not mean a linear and/or integral voice. On the contrary, the general effect is, let us say, one of accumulation and disorder, which results not in the strong and lasting presence of a subject, but in its dissipation.

Clarice’s chronicles resemble much more an act of emptying the subject, in which biographical fragments undoubtedly surprise. Perhaps we could extract from them this pedagogical/ontological summary: speaking of oneself, excessively, quickly, mechanically, one ceases to be. And if I used the word “act” above, I deem the term ritual more accurate in its imprecision. Approaching mystery and silence, the impersonality of the typewriter and of animals, the sensation of death and of God, the author herself is surprised by the precipitation of her intimacy, as if she came back to herself — becoming again — and, in in the midst of the flow, wanted to retreat: “As in everything, in writing I am also somewhat afraid of going too far. What would that be? Why? I retain myself, as if I retained the reins of a horse that could gallop and lead me to God knows where. I keep my guard.”18

None of this, however, responded to an intellectual call. The demand came from intuition, from a rapture prior to the mechanisms of a strict rational knowledge. Thus, Clarice speaks of an urge to write that can take place as “pure impulse – even when I have no theme.”19 And she adds: “But who? Who obliges me to write? That is the mystery: no one. Nonetheless, I still feel this compulsion to write.”20 Later, she would come to very clearly formulate her view of the creative process: “To tell the truth, one cannot think of content without form. Only intuition touches the truth without need of content or form. Intuition is the deep unconscious that does without form, while it itself works before surfacing.”21

Recalling that Clarice incorporated some chronicles into her novel An Apprenticeship or the Book of Pleasures, I imagine that Todas as crônicas could be called “An Unlearning:” “I no longer know how to write but the literary aspect has become so unimportant in my life that not being able to write may be precisely what will save me from literature.”22 Writing, the chronicler learned how not to write, while literature became, consequently, a strange gift — “writing is a curse” —, for only by means of it, accepting its unimportance, would there be any chance of achieving that which really matters, the unknown object that writing promises: “So what has become important to me? Whatever it may be, it will probably manifest itself through literature.”23

These speculations about writing and its mysteries can sound quite amusing, thanks to declarations whose frankness disdains any shadow of pride: “When I am not writing, I simply do not know how one writes. And if this most sincere of questions did not sound childish and sham, I would seek out some friends who are writers and ask them: how does one write?”24

A rare faculty of knowledge is in action through instruments that are inaugurated at every use, such that the revelation of what will be said and the act of saying are confused, with no chance of paving some minimally stable, repeatable awareness, or even, without configuring an ability: “Sometimes people wishing to pay me a compliment tell me I am intelligent. And they are surprised when I tell them that being intelligent is not my strong point and that I am no more intelligent than other people. They then accuse me of being modest.” It is once again intuition that comes to the forefront, constituting an intelligent way of operating in the dark: “But often this so-called intelligence of mine is so limited that one would think I was stupid. People who refer to my intelligence are, in fact, confusing intelligence with what I would call a knowing sensibility. Now that is something I really do possess. […] I daresay this is the kind of sensibility I exercise when I write, or in my relationships with friends. I also exercise it when I come into superficial contact with certain people whose aura I can sense immediately.”25

Such a willingness to attest to the feasibility of writing outside the contours of a formal intelligence concerning literature gives rise to clarifications that are never lacking in humor and irony. After proclaiming that she is not a “literati,” because she has not made writing books — written “spontaneously” — either a profession or a career, Clarice wonders if she is an “amateur.” And without answering, she continues: “I also find it difficult to dissuade certain people from calling me an intellectual. Once again, I am not being modest but simply… intellectual, one has to exercise, above all, one’s intelligence. What I exercise is not so much intelligence but intuition and instinct. To be an intellectual means being someone who is learned. I am such a poor reader that I must shamelessly confess that I really have no great learning. […] Nowadays, despite often being lazy to write, sometimes I am lazier when it comes to reading than to writing.”26

The completely unencumbered humor often arises from misunderstandings concerning her intelligence or intellectual gifts, as in the episode in which a friend tells her that some consider her, Clarice, “highly intellectual” and deem that she is very cultured. Her friend says that the author of The Apple in the Dark should, “just not to be embarrassed,” take care of her bookcase, which seemed to her very diminished. The delightful conclusion of the scene comes in the following terms: “But really je m’en fiche. I secretly pretend to let them think whatever they want. Since I do not regret really being ‘diminished’ – in other things it hurts – I am pure when it comes to feeling the taste of success. […] In the beginning I tried to tell the truth: but they thought I was being modest, was lying, or was being ‘weird.’”27

It is worth recalling that the vast majority of these texts were written from the second half of the 1960s until the middle of the following decade, a period marked by the counterculture and its ramifications. Clarice, calmly but vigorously defending a marginal place with regard to the literary institution, to its regulations and apparatus, seems to harmonize with that contestatory spirit, as if her more profound vocation had coincided with the youth of her time. It is quite eloquent, and moving, that on February 17, 1968 her non-chronicle is a letter to the Minister of Education, in which she refers to the unfair distribution of student openings at universities, whose conclusion comes with the following sentence: “Let these pages symbolize a march of protest on the part of young men and women.”28 A little later, on June 29 of the same tumultuous year of 1968, the chronicler, speaking directly to one of her readers, intrepidly asserts: “The students are shouting all over the world, Élcio. And I shout with them.”29

I realize at this point that I did not say what the recurrent themes of these chronicles are. In a very brief and hardly responsible list, I would include: taxi drivers, housemaids, animals, God, justice, the urgent need for us to preserve indigenous lands and undertake agrarian reform in the country, fear, her burned hand, indifference, Chico Buarque, the sea, readers, loneliness, silence, hunger, love, her children. I should also have mentioned the various, unusual interviews with people such as Pablo Neruda, Nelson Rodrigues, Millôr Fernandes, Tom Jobim, and Zagallo.

I shall quote one more passage, almost like a P.S. (it was a party, a meeting of Clarice and some friends, including the author of The Devil to Pay in the Backlands): “Guimarães Rosa then told me something I shall never forget, it made me so happy. He told me he read my books ‘not for the literature, but for the lessons in life.’ He quoted whole sentences by heart which I had written and I did not recognize any.”30

* Translated by Marco Alexandre de Oliveira and edited by Sean McIntrye. All quotes from the Portuguese original are free translations unless otherwise indicated.

** This text was originally published on April 1, 2019 in the magazine Quatro cinco um.

Author’s note

Some texts published in The Discovery of the World are not in Todas as crônicas because they are part of The Complete Stories.

Notas

1 Clarice Lispector, Selected Crônicas. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. New York: New Directions, 1996.

2 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Pagam-me para eu escrever. Eu escrevo, então.”

3 Clarice Lispector, Selected Crônicas. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. New York: New Directions, 1996.

4 Clarice Lispector, Selected Crônicas. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. New York: New Directions, 1996.

5 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Quero falar sem falar, se é possível.”

6 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “O Jornal do Brasil está me tornando popular. Ganho rosas. Um dia paro. Para me tornar tornada; Sei que o que escrevo aqui não se pode chamar de crônica nem de coluna nem de artigo. Mas sei que hoje é um grito. Um grito! De cansaço. Estou cansada!”

7 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Sou uma colunista feliz. Escrevi nove livros que fizeram muitas pessoas me amar de longe. Mas ser cronista tem um mistério que não entendo: é que os cronistas, pelo menos os do Rio, são muito amados. E escrever a espécie de crônica aos sábados tem me trazido mais amor ainda. Sinto-me tão perto de quem me lê.”

8 The original quotes in Portuguese read: “Sei que não sou, mas tenho meditado ligeiramente no assunto;” “Na verdade eu deveria conversar a respeito com Rubem Braga, que foi o inventor da crônica. Mas quero ver se consigo tatear sozinha no assunto e ver se chego a entender.”

9 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “As you all can see this is not a column, it’s just conversation.”

10 Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992. Note: Some fragments of the quote were unavailable and therefore translated freely.

11 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Noto uma coisa extremamente desagradável. Estas coisas que ando escrevendo aqui não são, creio, propriamente crônicas, mas agora entendo os nossos melhores cronistas. Porque eles assinam, não conseguem escapar de se revelar. Até certo ponto nós os conhecemos intimamente. E quanto a mim, isto me desagrada. Na literatura de livros permaneço anônima e discreta.”

12 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Nesta coluna estou de algum modo me dando a conhecer. Perco minha intimidade secreta? Mas que fazer? É que escrevo ao correr da máquina e, quando vejo, revelei certa parte minha. Acho que se escrever sobre o problema da superprodução do café no Brasil terminarei sendo pessoal. Daqui em breve serei popular? Isso me assusta. Vou ver o que posso fazer, se é que posso. O que me consola é a frase de Fernando Pessoa, que li citada: ‘Falar é o modo mais simples de nos tornarmos desconhecidos.’”

13 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Ah, isto não é crônica nem coluna, bem sei. Por uma vez acho que não importa: os dias correm, a máquina corre. Mas se eu fosse cronista, ah não me faltariam assuntos!”

14 Clarice Lispector, Selected Crônicas. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. New York: New Directions, 1996.

15 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Meu Deus, como o amor impede a morte! Não sei o que estou querendo dizer com isso: confio na minha incompreensão, que tem me dado vida instintiva, enquanto que a chamada compreensão é tão limitada.”

16 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Estou escrevendo com muita facilidade, e com muita fluência. É preciso desconfiar disso.”

17 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Com perdão da palavra, sou um mistério para mim.”

18 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Como em tudo, no escrever também tenho uma espécie de receio de ir longe demais. Que será isso? Por quê? Retenho-me, como se retivesse as rédeas de um cavalo que poderia galopar e me levar Deus sabe onde. Eu me guardo.”

19 Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992.

20 Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992.

21 Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992. Note: Some fragments of the quote were unavailable and therefore translated freely.

22 Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992.

23 Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992.

24 Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992.

25 Clarice Lispector, Selected Crônicas. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. New York: New Directions, 1996.

26 Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992 Note: Some fragments of the quote were unavailable and therefore translated freely.

27 The original quotes in Portuguese read: “altamente intelectualizada;” “grande cultura;” “só para não se envergonhar;” “Mas realmente je m’en fiche. Brinco toda secreta de deixar que pensem o que quiserem. Como não tenho remorsos de ser realmente uma ‘desfalcada’ — em outras coisas me dói — estou pura para sentir o gosto do logro. […] No começo tentei dizer a verdade: mas tomavam como modéstia, mentira ou ‘esquisitice.’”

28 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Que estas páginas simbolizem uma passeata de protesto de rapazes e moças.”

29 The original quote in Portuguese reads: “Os estudantes estão gritando em todas as partes do mundo, Élcio. E eu grito com eles.”

30 Clarice Lispector, Discovering the World. Translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1992. Note: Some fragments of the quote were unavailable and therefore translated freely.