, Flying over Brasília – by Carlos Mendes de Sousa. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2017. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2017/09/18/brasilia-em-sobrevoo/. Acesso em: 19 April 2024.

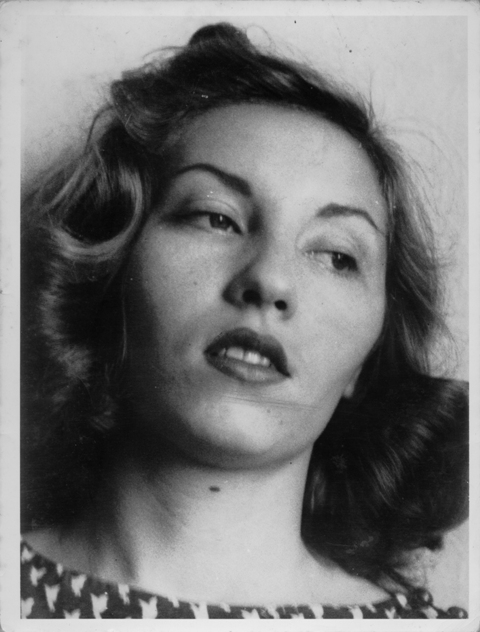

The Moreira Salles Institute, in partnership with the Humanities Department of Columbia University, held the international seminar The Clarice Factor: Aesthetics, Gender, and Diaspora in Brazil, which occurred in March, in New York.

With discussions dedicated to Clarice’s writing as performance, form, sound, and matter, the panels included teacher-scholars from several universities, including Vilma Arêas (UNICAMP), Yudith Rosenbaum (USP), and Carlos Mendes de Sousa, whose text is available here.

Flying Over Brasília

Carlos Mendes de Sousa¹

Today is Sunday in New York. In fulgent Brasília, it is already Tuesday. Brasília simply skips Monday.

Thresholds

Threshold 1 – A date outside the text, 1976

Biographers are unanimous in relating Clarice Lispector’s contentment when on her last trip to Brasília, in 1976. Clarice had traveled to the city to receive the recognition award for her work granted by the Federal District Cultural Foundation. In the previous year, Brasília had acquired some visibility in the author’s work with the publication of a relatively extensive text about the city. Would this text be what led Clarice back to Brasília? This last trip symbolically crowns the connection between the name of the writer and the name of the city.

Threshold 2 – Founding dates, approximations: The Apple in the Dark and Brasília

Does The Apple in the Dark announce Brasília? The approximate links would derive from the dates, from the vicinity of the times: the time of the conception and construction of Brasília (1956/1960) and the time of the creation and appearance of The Apple in the Dark. At the end of this book, we find the note: “Washington, May 1956;” the novel was only published in 1961. With due consideration of that which cannot be compared, certain connections can be found: the architecture and the monumental; the estrangement and the astonishment; poetry and modernity. All of this unites these two works that bring with them a foundational difference. But the repercussions of the analogies go further. What Clarice says about Brasília could perhaps be said of her own texts, especially The Apple in the Dark, a fascinating book, without corners, where it is necessary to learn to inhabit it. And what Niemeyer says about the city could also be applied to Clarice: “you can like or detest Brasília. But you cannot say that you have ever seen anything similar.”

Let us approach Clarice’s literature as we approached Brasília. I experienced this in 1992, after an 18-hour trip, when I crossed Guimarães Rosa’s sertão backlands and arrived at Brasília by Clarice’s hand; and when I experienced the intermutation of the terms: Brasília – new literature. Clarice – new city.

The diptych

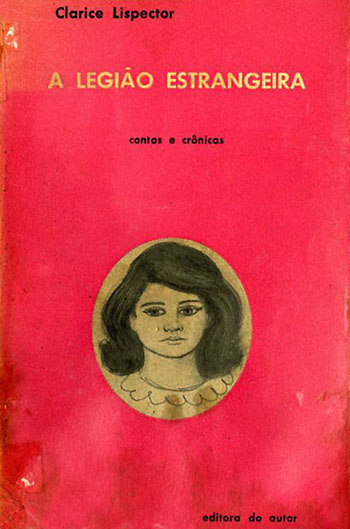

Right after the foundation of Brasília, Clarice visited the city. Following this visit, she wrote a text with the title “Brasília: Five Days,” first published in the “Children’s Corner” column in Senhor (1963) magazine, and collected in the following year in “Back of the Drawer,” the 2nd part of the book The Foreign Legion. In 1974, Clarice returned to the city and wrote a more extensive text, “Brasília: Splendor,” published in the anthology Vision of Splendor (1975), in which it appears as an afterword to the text written at the time of her first trip.

The combination of two texts, from different times, with explicit reference to the dates of writing, constitutes a singular situation within the work. As a transition between the two blocks, there is a small fragment in which the two moments are explained: “I went to Brasília in 1962. What I wrote about is what you have just read. And now I have returned twelve years later for two days. And I wrote about it too. So here is everything I vomited up. / Warning: I am about to begin. / This piece is accompanied by Strauss’s “Vienna Blood” waltz. It’s 11:20 on the morning of the 13th.”

It is important to emphasize the fact that the two texts collected under the name “Brasília” constitute a central piece in the book Vision of Splendor (1975). The attention that the author grants to them is well known, starting with the reflection in the name chosen for a title of the anthology and due to the fact that the diptych opens the book. It seems as though Clarice designed a book that would include the text which resulted from the visit to the city in 1974. It may also appear as though such a choice likewise resulted from the desire to give emphasis to the first text, by naturally accompanying the selection of other already published chronicles (included in Vision of Splendor).

The brevity of the two visits clearly contrasts with the long consideration of the city expressed in the texts that she dedicated to it. Does entering Brasília by Clarice’s hand allow one to see the construction of the city as a construction of a literature?

The Flyover (1)

If the flyover metaphor can be reconsidered in texts related to the planning of the city of Brasília, we also find it in Clarice. For example, in Água Viva, when there is a reference to the way of seeing the text as if viewed from an airplane. The metadiscursive moment (the “explanation” about the image of the aerial view) becomes particularly relevant here. It is the distance that allows for the discernment of the difficult order: “This text I give you is not meant to be seen up close: it gains a secret roundness previously invisible when seen from a plane at cruising altitude. Then one can guess the set of islands and one sees channels and seas.”

But it is necessary to clarify right away that if we find the metaphor in Clarice, she is not the one who proposes the flyover reading perspective. It is clearly the point-of-view of the critic/reader that leads to this view. It is not difficult for us to place the work into perspective and find in it successive points of arrival that are constituted as points of departure. It is easy for us to find justifications when we think of the novels. In the beginning, the middle, or the last phase, the differences and similarities allow our arguments to be based on changes that involve new beginnings. I am thinking of The Besieged City, The Passion According to G.H., and Água Viva, but I could also think of The Apple in the Dark, An Apprenticeship or the Book of Delights, etc. And the short story collections could also be viewed from this perspective of the path taken or of an inaugural meaning. I read “Brasília” in this way, as a path to a revisitation, by pointing out a few connections, a few points that likewise allow for a look at the rest of the work.

One of the greatest implications of the combination of the two texts about Brasília into a diptych results precisely from the possibility that is provided by a reading of the work in perspective, taking into account the dates in which the “chronicles” were written, the contexts in which they appear, and the dialogue established with other works by the author. The first text refers to the key period in which the writing of some of Clarice’s most emblematic books is situated: between the novels The Apple in the Dark and The Passion According to G.H. and between the books of short stories Family Ties and The Foreign Legion.

The differences between the two blocks are eye-catching. The first, which is more compact, produces an effect of greater closure. Despite the existence of elements that provoke estrangement, it bears a marked sense of cohesion based, to a large extent, on its approach to storytelling, in the recreation of a very particular founding story. The second block is marked by the fragmentation that is immediately observable in the formal layout, through the presence of very short paragraphs.

The first text reflects the period in which it was written, very close to the inauguration, however, as one might expect, it reflects it in Clarice fashion. The amplitude and distance grow in the speaker who tells of the strangeness of the place. The writing of this first text alludes to chapters of The Passion According to G.H. (such as Chapter 18), but also to fragmentary texts from the 2nd part of The Foreign Legion, where it appears, and even to other texts from the 1st part, such as “The Egg and the Chicken.”

As for the second text, we are immediately led to contextualize it in the framework of Clarice’s production from the 1970s, which is particularly marked by the sign of the fragmentary. It is important to consider a reading perspective that relates the texts from the different phases, obviously taking into account the specificities of the moments. In this framework, I would like to highlight the book Água Viva, from 1973. Here one considers not only the book as we know it, but also what is represented by the tense moment that led to its concretization and that was visibly expressed in the evident transit in the copy of “Screaming Object” (a typescript that precedes this book), as well as in testimonies that allow us to accompany this process (like some letters exchanged with José Américo Motta Pessanha regarding the actual publication of this work). It is important above all to point out that a sort of distancing or a very expressive new direction will be performed in the texts published as of 1974. Incidentally, see how, right after the release of Água Viva, this work was analyzed with respect to its novelty, in its differences and also its similarities (in mode of concentration). In the beginning of 1974, in a review published in the Tribuna da Imprensa, Reynaldo Bairão highlighted the book’s formal renovation, giving an account of the fact that, in it, there is simultaneously “a sort of summary of all her previous fictional work.”

I intend to show that Clarice’s “Brasília” is a place where, as if distractedly, a thousand doors are opened. In this way of presenting the city, all of Clarice is right there in the end. As if she unwittingly placed, on the same plane, the high and the low, autobiographical and identitarian issues, literature and truth, life and death; but also play and humor, bewilderment and deflation.

In the beginning… the story

In the first block, Brasília appears associated with light and blindness, with the gelidity of crystal. The incidence of raw light enhances the exile. One speaks of the buried city that rises from the rubble; it was nature that was charged with hiding it until it reappeared one day. This is the motif of the story. One may speak of a theory of strata (the past, the present, the future) that determine the layout and existence of the city. One represents a city that fulfills the attributes of circular mythical places: the concretization of an abstraction or idealization (“rounded streets … without corners”).

Look at the implications of the founding story, in Clarice’s writing, and the way that the writer herself will deconstruct this view. We find the return to a fantastic past that is reinvented based on real facts: “I regard Brasília as I regard Rome. Brasília began with a final simplification of ruins.” The elements that are referred to an empirical reality are anchored in a recognizable historicity, but the dominant movement is that of the amplification which overcomes these references. A flowering Antiquity (the 14th century A.D.) mixed with a timeless present returns us to the book The Besieged City, one of the foundational novels (of her own name, of her writing). At a given moment, it is said of Lucrécia that she is “Greek in a city not yet erected,” finding names for things, a resonance that will extraordinarily and sumptuously echo loudly in the aforementioned Chapter 18 of The Passion According to G.H.

In the first paragraph from the first block of “Brasília,” the author experiences, for a brief period, the impact of the new city. The account emphasizes this perspective. The invocation of the founding story (to take account of what is seen and felt) underscores the dawning moment (supported by the first analogy: the creation of the world), and the readers of Clarice Lispector, in turn, cannot avoid invoking the author’s work (specifically the initial phase, where many revisitations of founding myths are found). The issue of the deterritorialization performed by her literature reverberates here. In this sense, the identification between Clarice and the city of Brasília gains strength: she is Greek, Roman, and Brasiliarian, also. The confrontations with the place of estrangement are the estrangement from herself. The observer’s focus unveils her alien condition, which sets in continuous motion her propulsive self-consciousness and otherness.

The trip

The view of Brasília is a guest view based on the perspective of Rio de Janeiro. And nonetheless, Brasília is the city that evoked a more extensively concentrated text.

The interrogations about Brazil, the attempts to understand the country based on this strange place, which is the new city, are recurrent in the 1960s. I recall different outside perspectives that are somewhat coincidental, such as that of the sociologist Max Bense, who dwells on its Cartesianism and its amalgam, or that of the poet Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, who speaks of the “logical and lyrical” city. In Brazil itself, there are recurring views that take account of the estrangement. One cites as an example the short film by Joaquim Pedro de Andrade – “Brasília: contradições de uma cidade nova” (Brasília: contradictions of a new city).

The interest in Brasília is something that naturally involves all Brazilians. Even so, it is important to ask: why such an explicit and prolonged attention to a city? It is not difficult for one to make a very complete survey of Clarice’s geography. By memory, whoever knows her work may present a chart that succinctly allows one to accede to a synthesis in which various places in the city of Rio de Janeiro are highlighted.

One must not forget the founding meaning integrated into the arch that the construction of the work presents. The city, in the first books, is the city with minimal references to any connection of a locatable geographical order. In the 1949 book, in whose title generically appears the word “city,” a certain atmosphere is asserted, with a landscape that is crudely extraterritorial, that is, prevailingly abstract.

From the mappable places and objectifiable impressions, in “Brasília,” we are quickly confronted with lines of flight. The reason for the dislocations reverberates in the texts: from the familiar resonances of the first trip (in the reference to her children) to the explanation of the reasons for the second dislocation (the lecture given). Since we cannot exhaustively present here the presence of the map, let us see examples from the beginning of the second block. We read in a paragraph, which refers to the visit to the Dom Bosco church, the admiration for the “splendid” stained glass, the contemplative stillness: “[The church] has such splendid stained glass that I fell silent seated on the pew, not believing it was real.” But soon a dissonance is mentioned and an action plan suggested: “The only flaw is the unusual circular chandelier that looks like some nouveau riche thing. The church would have been pure without the chandelier. But what can you do? go at night, in the dark, and steal it?”. The text progresses alongside the map: “Then I went to the National Library;” it progresses with references to sensations, with references to that which marks the visiting writer’s contact, and with her way of interacting with defining elements of the city; it progresses with precise references to the hunger that she feels, in the cold, in the light, in the dry air. Very quickly, the narration allows itself to be contaminated by that which is disconcerting, that which escapes the conventionalism of the travel account or the chronicle: “What hunger, but what hunger. I asked if the city had a lot of crime. I was told that in the suburb of Grama (is that its name?) there are about three homicides per week. (I interrupted the crimes to eat).”

Transits, accommodation

The visit to the city and the return presuppose a movement that is asserted in the account and that highlights the sign of accommodation. Two aspects are notable in relation to this question: the counterpoint with other cities, other places summoned in the text, and the Brazilian question. The sign of accommodation is particularly active in the second block (“Brasília: Splendor”), which is marked by the pendularity between Rio de Janeiro and Brasília, a movement that paces the whole text. One observes, nonetheless, a mixture that at times seems to cause confusion and that involves the transit between the two cities – the location where one arrives and the place from where one has departed and to where one returns.

Let us see the first four paragraphs of the second block. The length of the first two is similar. The third paragraph is smaller and the fourth is much shorter. Just one sentence: “I pause for a moment to say that Brasília is a tennis court.” After this pause, the following paragraph begins like this: “There is a reinvigorating chill there.” The adverb points to the place that is the object of attention. It is from here that a few contradictions occur from the speaker’s perspective, which are pointed out by the author herself, about the times of writing and about the places. “I’m talking about Rio. Hello, Rio! Hello! Hello!”; “Tomorrow I return to Rio, turbulent city of my loves;” “In Rio, in my pantry, I killed a mosquito that was quivering in midair;” “It is daybreak here in Rio;” “Does Brasília have gnomes? / My house in Rio is full of them.” In Brasília, Clarice finds a world in her own image and likeness, a land where she can tread. Paradoxically, the city allows for the return to the place where the exiled is recognized. The threatening angel of expulsion prowls, but is absent.

The approach to Brasília may take place through the political meaning of the new capital. In Clarice’s chronicles in the Jornal do Brasil, we sometimes come across her concern with the national question. Gilberto Figueiredo Martins, in the book Estátuas Invisíveis. Experiências do espaço público na ficção de Clarice Lispector (Invisible Statues. Experiences of Public Space in the Fiction of Clarice Lispector; São Paulo, Edusp, 2010), presents a reading with this focus, taking account of a difference in the second text with regard to the first, which reflects the political moment. The law of the accommodating city is asserted in some moments and incites confrontation. We read there the reference to “implacable Brasília” and to the implacable green eye, to the city that “arrests” and that deprives one of documents, identity, veracity, and intimate breath, and finally, to the city that leads to crime. But already in 1962, Clarice spoke of the “totalitarian state.” When she interviewed Oscar Niemeyer, she confronted him with this judgment: “I once wrote: ‘The construction of Brasília: that of a totalitarian state.’ What do you think of my impression, Oscar?” In the same interview, there arises a concern in relation to how the city could fulfill the concretization of the democratic ideal consonant with the architectural project. In 1972, when she interviewed Paulo and Gisela Magalhães, architects who worked in Brasília, she clearly affirmed: “When I was there many years ago, it seemed to me a deserted city.” And furthermore: “My primary impression, already very old […] and what I saw in the beginning of Brasília, was that of a city from the Far West of films, with saloons and shootouts.”

The dislocation is made to a place that stimulates reflection. The return to the point of departure is to be simultaneously inside and outside. In the return, as if it were an improvisation, there arises a torrent of memories, in a record of fleeting images. The acceleration projects multiplying mirrors, a way of escaping fixity.

The counterpoints encounter, in opposition, precise references: New York, Capri, Bahia, Ceará, Recife, Lisbon… What time is it? How does one live? If Brasília points to a trans-historical and trans-temporal dimension, the inhabitant of the land of Clarice Lispector also asks that there be room for the banalized terrain.

Writing, text: hybridities

The expected references in a chronicle text, the objective impressions and various referential notes (geographical, architectonic, climactic, social, etc.), everything that is in the factual domain is projected into another sphere. We are continually transported to the domain of overcoming and transmutation. The cold, the light, the color of the earth, the trees, the traffic, etc. are transformed into Clarice’s signs. Everything becomes widely pulverized, surpasses the immediate. Factual data is continuously intertwined with fantastic allusions, such as when between parentheses the narrator affirms that she interrupted “the crimes to eat.” Or when it is said that the rats of Brasília eat human flesh.

In the proposed view, the creative impulse permanently echoes: “my insomnia is me myself, it is lived, it is my astonishment;” “They erected inexplicable astonishment. Creation is not a comprehension, it is a new mystery.”

One may then affirm that Clarice’s “Brasília” is the mirror of the text: the author captures the city in its time, which is that of a recognized strangeness. Mirrored, the city encounters itself. By reading the places, we, the readers, recognize everywhere the topics of Lispector’s universe. Places in perspective: the world is as many ways as Lispector tells us it can be seen and even more so as we, Lispectorized, come to see it.

“Brasília” is where genre no longer holds, it has always been the whole work escaping labels. It is in Água Viva that we find the indicated gesture, the maxim “genre no longer holds with me.” Actually, the gestation of this book accounts for the process and bears this explicit mark. On a page that follows the cover page of the typescript “Screaming Object,” consider what could be a draft for a proemial note similar to those that appear in The Passion According to G.H. or An Apprenticeship or The Book of Delights (the previous two novels). Two texts intersect on this page; the ink color is different:

This is an anti-book. The core is “it”.

If you consider this more than a letter, be aware that it is an anti-book.

But the phrase “genre no longer holds with me” could be placed as a subtitle to the beginning of the work, already in Near to the Wild Heart. And the indication for “Screaming Object” dialogues especially with “Brasília” if we think of the approximations with another text that is difficult to classify, “Report on the Thing,” which, when published in the Jornal do Brasil column, received the name “Objeto: anticonto” (“Object: antistory”). There Clarice presented an explanatory note:

“Note: this report-mystery, this geometrical anti-story was published in São Paulo’ Senhor magazine. In his introduction, Nélson Coelho says that I have killed the writer in me. He cites several writers who have attempted suicide of the written word. None succeeded. ‘Just as Clarice shall not succeed’, Nélson Coelho writes.

What did I attempt with this type of report?

I think that I wanted to write an anti-story, an anti-literature. As if that way I might demystify fiction. It was a worthwhile experience for me. It doesn’t matter that I have failed. It is called: OBJECT.”

For this purpose, it is interesting to highlight the inclusion of “Brasília” in the volume The Complete Stories, edited by Benjamin Moser. The plurivocity of registers (from short story to chronicle) embraces the opening on the plane of enunciation.

Signs of flight: spectral Brasília, the interrogation, the assumption of one’s own death

In opposition to the reinforced concrete, the monumental edifices, the solitude, the earthy, the solemnity of the opening of the new city born out of nothing, there arises the spectral city that vanishes, the city that levitates, the fluctuation, the diffuse: “Am I being levitated? Brasília suffers from levitation.” What causes the loss? What phantasmatically disappears? What can be shown and what escapes the subject of perception is permanently at play. The inquisitive bent becomes evident, the enunciations associated with the idea of flight. Why put the questions? Why Brasília? The text is rife with interrogations. And at every moment we come across the doubtful enunciation that results in double premises which always presuppose more than one path. Even the possibility of changing one’s mind and leaving matters unresolved:

Could there be Brasília? That settles it: what I’ll do is buy a green hat to match my shawl. Or should I not buy one at all? I am so indecisive. Brasília is decision. Brasília is a man: And I, such a woman. I go bumbling along. I stumble into something here, I stumble into something there. And arrive at last.

I’ve settled it: I don’t need a hat at all. Or do I? My God, what shall become of me?

Did I say it or not […]?

Didn’t I say that Brasília is a tennis court? Because Brasília is blood on a tennis court. And as for me? Where am I? Me? poor me, with my scarlet-stained handkerchief. Do I kill myself? No. I live in brute reply. I am right there for whoever wants me.

The assumption of her own death is another marked sign of flight. One will see how the strange formulation “died” presents an ontological impossibility in itself. Everything is quickly perceived – suddenly, everything is past, forgotten, and what the quickness leaves in our hands is a small emptied time. In the first block, the look of astonishment over the newborn city is projected in time travels, concretely in a future afterlife, and in a fabulously reinvented past:

– When I died, one day I opened my eyes and there was Brasília. I was alone in the world. There was a parked taxi. Without a driver. Oh how frightening.

– Momma, it’s lovely to see you standing there in that fluttering white cape. (It’s because I died, my son).

The disarming and obsessive enunciation of death itself opens up the places of flight, the phantasmatic places. In the second block, this appearance is reconsidered and expanded into more and more disconcerting formulations in which humor and an elevated tone are mixed:

I. The phantasmagoric one. My name does not exist. What exists is a picture faked from another picture of me. But the real one died already. I died on the ninth of June. Sunday. After lunch in the precious company of those I love. I had roast chicken. I am happy. But lack true death. I am in a hurry to see God. Pray for me. I died elegantly.

I am going to last a while yet. No one is immortal. Just see if you can find someone who doesn’t die. I died. I died murdered by Brasília. I died to pursue research. Pray for me because I died on my back.

Voices, rhythms, respirations, flows. The brainstorm.

The encounter with the city of Brasília causes an outbreak that stems from the anarchic energy of the voice. A flow, a manifesto against the programmed city. Look at the expressions, words, graphic resources – an explosive creativity (contrary to what is written about Bern or about other places, in the antipodes of Brasília). Look at the strangeness of the formulations that account for the extraordinary inventiveness: “I love you, oh extragantic one! Oh word that I invented and do not know the meaning of.” The examples can be listed, among many others. Such as the paragraph with the highlighted sentence: “Brasília is a wildly twinkling blue eye that burns in my heart.”

The discourse progresses admirably at will. Brasília is an image-making machine. The threads are untangled, dismantling (feinting and dribbling) the commonplace. The dualities and alternances dominate: from the exalted, glorified image, to the humiliated figure. Spontaneous perceptions are associated with the account of the unpredictable. Semantic constellations instigate perspectives on perspectives.

Brasília allows for a series of crossings, games, interrelations. A crossroads-text: reference notes, fantastic accounts, autobiographical fragments, humorous and parodic tirades. In the whole text, this cosmophagic centering is greatly relevant: “I call humbly for help. They’re robbing me. Am I the whole world? General astonishment.” One then immediately reads the following: “This isn’t a high wind, sir, it’s a tornado.” Further ahead: “The monstrous typewriter. It’s a telescope. Such wind. Is it a tornado? It is.” The intensity is the degree to which Clarice invests herself. She is a cyclone. At the service of stylistic novelty, which marks the flight from and the shattering of the text, we encounter devices that wrap and unwrap the sentences: words with hyphens inside syllables or letters (a way of making them more audible?), incomplete sentences, different formulations (“There people have dinner and lunch together – it is to have people to populate them”), the very marked repetitions: “Feeling good, feeling good, feeling good. I’m in a good mood.” The experimentation, the renovation of language are not gratuitous. The speaker’s perception is disconcerting and is supported by the segmentation, the accumulation, the impertinent chains, the hallucinatory rhythm, the strange similes, and the disturbing portrait.

In “Brasília”, as in “Report on the Thing” or even earlier in “The Egg and the Chicken,” the brainstorming that Clarice will adopt in the texts from her last phase gains strength. In Where You Were at Night, it really appears in “Soul Storm.” There are loose sentences that echo in Brasília, intersecting thoughts, uncertain sayings, aphorisms, voices, echoes (we encounter a passage in which the narrator presents herself as a receptacle of voices that she records), wordplays (“Seus” [Yours] instead of Deus [God]; and “iulf” instead of flui [flows]).

I am the words that I hear; we are the voices that we hear. In the vortex of speech, the dreams erected before us, the minute (or infinite) questions in proliferation. In the whirlwind into which the account throws us, sometimes, a halt is imposed, an arrow or a flash, a sparkle or unexpected image, before the return to the maelstrom:

I am no more than phrases overheard by chance. On the street, while crossing through traffic, I heard: “It was out of necessity”. And at the Roxy Cinema, in Rio de Janeiro, I heard two fat women saying: “In the morning she slept and at night she woke up”. “She has no stamina”. In Brasília I have stamina, whereas in Rio I am rather languid, sort of sweet. And I heard the following phrase from the same fat women who were short: “Just what does she have to go do over there?” And that, my dears, is how I got expelled.

The complexity of Clarice’s brainstorming, which embraces a diversity of strata, settles into tense movements from a surprising mixture of registers: of the fantastic climate associated with critical humor and with constant autobiographical references, with the cohabitation of disparate literary references. As in the register of chronicles, but much more free. The strength of the telegraphic discourse and the spontaneous discourse, the transcription of registers into other languages (especially English), the transcription of the syllabled words:

I want to return to Brasília to room 700. So I can dot the “i”. But Brasília does not flow. It goes in the opposite direction. Like this: wolf (flow).

Wolf backwards. How discourse flows! The denegation says the centrality. Clarice is not a turgid discourse, she is not a mouthful of hard stones. It is water that flows, dense water of stars and rare jewels, drinking water, life water. The narrator is caught up in the powerful impregnating force of the city. It is the disturbing effect (the inexplicability of the place) that, in part, unleashes the torrential discourse.

Projections: the flyover (2)

There is a criss-crossing of many axes in “Brasília.” More than any other text close to this one (think of “The Chicken and the Egg,” “Report on the Thing,” or “Where You Were at Night”), here is a path which is similar to that of the announcements in Hour of the Star. One can also glimpse in “Brasília” an evident twinning with A Breath of Life: the dialogue and the interchanges between the “Author” and “Ângela” are on the same plane as the narrator’s dialogue in “Brasília: Splendor” with the city.

Almost at the end of the second block, we read: “I am innocent and ignorant. And when I am in a state of writing, I don’t read. It would be too much for me, I don’t have the strength.” Declarations of this sort anticipate the arrival of the alter ego Rodrigo S.M. (likewise present in The Via Crucis of the Body, in the character Cláudio Lemos). That which in the beginning of the first block of “Brasília” was a reflection of mirrors (the author spoke of the mystery of the architect’s creation, speaking of herself), is now an explained meta-literary inclination. The reversibilities are similar (“so much we interchanged”) and there are many similarities found in the domain of metadiscursive reflection. Look at the closeness in the formulations:

Brasília – It’s an adventure: it brings me face to face with the unknown. I’m going to speak words. Words have nothing to do with sensations. Words are hard stones and sensations are ever so delicate, fleeting, extreme.

The Hour of the Star – “Its rhythm is frequently discordant. It also contains facts. I have always been enthusiastic about facts without literature – facts are hard stones and I am much more interested in action than in meditation. There is no way of escaping facts.”

No, it is not easy to write. It is as hard as breaking rocks. Sparks and splinters fly like shattered steel.

On the plane of enunciation, the relation of the narrator (the writer Clarice Lispector) with the city is very close to that which the narrator Rodrigo S.M. establishes with Macabéa:

Brasília is slim. And utterly elegant. It wears a wig and false eyelashes. It is a scroll inside a Pyramid. It does not age. It is Coca-Cola, my God, and will outlive me. Too bad. For Coca-Cola, of course.

Oh, what a pretty nose Brasília has. So delicate.

The text presents us with real and fictional characters (in the library, the airport, the airplane) and reveals Brasília the character. With liberty, and in a register full of humor, the narrator interpellates the city, speaks to the city, to distantly better contemplate it. The unveiling results from the persecution and saturation of the figure, an obsessive procedure that is Lispectorian par excellence.

The sign of privation is very marked: “city with no corners/ Neither does it have any neighborhood bars for people to get a cup of coffee / It’s true. I swear I didn’t see any corners. / In Brasília the everyday does not exist.” In the aseptic city, errors have been eradicated. One demands a revision. Because inhabitability, the place for the human, presupposes the fundamental incorporation of error. At the end of a paragraph, one reads a sort of maxim: “Brasília is a joke, strictly perfect and without error. And the only thing that saves me is error.”

Through play, from parody to humor, one continuously seeks to preserve mistakes. Here we are also led to approximations with many of Clarice’s characters, especially Macabéa:

Brasília is a Wedding March. The groom is a northeasterner who eats up the whole wedding cake because he’s gone hungry for several generations. The bride is a widowed old lady, rich and cranky. From this unusual wedding that I witnessed, forced by circumstances, I left defeated by the violence of the Wedding March that sounded like a Military March and commanded me to get married to and I don’t want to. I left covered in Band-Aids, my ankle twisted, my neck aching and a big wound aching in my heart.

And nonetheless, the challenge that the city provokes is up to the risk. Here one finds one of the strong traits identified with Clarice’s universe:

Brasília is risky and I love risk. It’s an adventure: it brings me face to face with the unknown. I’m going to speak words. Words have nothing to do with sensations. Words are hard stones and sensations are ever so delicate, fleeting, extreme.

One of the most expressive recurrences – the attempt to say by predication – translates an impossibility (“Brasília is…”). What else might this insistence want to say? In the second block, the irruption of these attempts reinforces the impossibility of description: “It’s becoming clear that I don’t know how to describe Brasília.” As in the whole work, one goes around an object or person, one incessantly seeks to reach it without managing to arrive at the nucleus.

In the play of approximations, two elements are noticeable: the dentist’s chair and the tennis court. The dentist’s machine in Brasília, a recurring motif, leads us to toothaches, to the “exposed nerve” in The Hour of the Star. The reference to the tennis court appears in a short story from Where You Were at Night, “The Departure of the Train,” a text that occupies a marked role in the domain of interrelations established among texts from her last phase. In the dual structure that the short story presents, the figure of Ângela Pralini is speaking to Dona Maria Rita, but projecting a dialogue with the absent character, Eduardo. The meaning attributed to the characterization of the character is close to that which begins to be invoked to describe the city, in the first occurrence: “I pause for a moment to say that Brasília is a tennis court.” The complexification is manifested as the text progresses:

Didn’t I say that Brasília is a tennis court? Because Brasília is blood on a tennis court. And as for me? Where am I? Me? poor me, with my scarlet-stained handkerchief. Do I kill myself? No. I live in brute reply. I am right there for whoever wants me.

And further on: “Remember how I mentioned the tennis court with blood? Well the blood was mine, the scarlet, the clotting was mine.” The process of identification evident here is what we will read in the reversible statements made by Rodrigo S.M. to Macabéa. And if blood could have a political reading, in the dismantling of the oppressive scenario of the military dictatorship, as Gilberto Figueiredo Martins (cf. Estátuas invisíveis) claims, this blood also means the return to the essence of being and to the experience of limits – the obsession for the heart, for the nucleus of life:

De onde no entanto até sangue arfante de tão vivo de vida poderá quem sabe escorrer e logo se coagular em cubos de geleia trêmula. Será essa história o meu coágulo? Que sei eu. (The Hour of the Star)

The speaker is the character Rodrigo S.M., who, in the “Dedicatória do Autor (na verdade Clarice Lispector)”, writes: “Dedico-me à cor rubra muito escarlate como o meu sangue de homem em plena idade e portanto dedico-me a meu sangue.”

We could continue to list examples. I will only recall the end of “Brasília,” which is so close to the ending of the last novel:

I know how to die. I have been dying since I was little. And it hurts but we pretend it doesn’t. I miss God so badly.

And now I am going to die a little bit. I need to so much.

Yes. I accept, my Lord. Under protest.

But Brasília is splendo.

I am utterly afraid.

Disclosure

In “Brasília,” an avowedly autobiographical voice is assumed, even if these notes irrupt loosely here, often in unperceived fashion. The inquisitive procedures underscore the purpose of hiding and disclosing the writer figure and the writing processes. There are many references to the mother Clarice, to her dog Ulisses, who occupies a privileged space in this text, to Coca-Cola, to taxi drivers, to housemaids, to the fortuneteller Dom Nadir from Méier…

Disclosures? Some. At other times the latency that incites us to interpret: “Oh, poor little me. So motherless […] It is a thing of nature. I am in favor of Brasília.”

In the framework of explanations, one recalls for instance the direct appearance of topics with strong resonance in the Lispectorian universe: “As I may have said, I want a beloved hand to hold mine when it is time for me to go.” And it is in “Brasília” that polished self-characterizations arise that would serve as a theme for biographers. Olga Borelli portrays her as such: “She carried herself with both the humility of a peasant and the pride of a great lady.” In Clarice’s voice, we read here: “Come on, I am a woman who’s simple and a tiny bit sophisticated. A mix of peasant and a star in the sky” Above all, what is sought in “Brasília” is what is sought in all her work: the self’s encounter with the self. A search that encounters here its highest expression in the interrogation about the emblem-figure of Clarice’s writing: “Brasília is an orange construction crane fishing out something very delicate: a small white egg. Is that white egg me or a little child born today?”.

¹ Carlos Mendes de Sousa earned his Ph.D. in Literature from the University of Minho. He is an associate professor in the Department of Portuguese and Lusophone Studies at the Institute of Arts and Humanities, University of Minho, Portugal, where he has dedicated himself to the study of Brazilian literature and modern and contemporary Portuguese poetry. He is the author of many books, including Clarice Lispector. Pinturas (Rocco, 2013); Miguel Torga: o chão e o verbo (Sabrosa / Espaço Miguel Torga, 2014); Clarice Lispector. Figuras da Escrita, (Instituto Moreira Salles, 2012), and O Nascimento da Música. A Metáfora em Eugénio de Andrade (Almedina, 1992).