, The thirst for the other. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2019. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2019/09/24/a-sede-do-outro/. Acesso em: 13 December 2025.

Every year, in the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church, Carnival is followed by Lent, a period in which the faithful withdraw from mundane life to dedicate themselves to sacrifices, charity, and prayer. In 2018, Pope Francis invited the Portuguese priest and poet José Tolentino Mendonça to give a lecture that would guide the reflections of the Roman Curia on the challenges faced by the Church in that year. The theme chosen by Tolentino, who was named archbishop for the occasion (and proclaimed cardinal on the 1st day of this month of September), was the “thirst of Jesus.” The text of the lecture was published in a book, under the title Thirst (by Paulist Press).

The presentation begins with the episode, described in the Gospel of Saint John, in which Jesus encounters the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well (John 4:5-24). Jesus was making the journey between Judea and Galilee, when, tired, he stops at the edge of the well to rest and the woman arrives there to fetch water. He sees her and says: “Give me a drink.” Right from the beginning, Tolentino alerts us that the thirst of Jesus is not for water; it concerns a greater thirst: “a thirst that wants to reach our thirst, to get in touch with our deserts, with our wounds.”

If at Jacob’s well Jesus asks the Samaritan for a drink, at the end of the Scriptures, he does the opposite; he offers himself, as a fountain: “And let everyone who is thirsty come […],” he says. And he makes the metaphor explicit: “Let anyone who wishes take the water of life as a gift” (Revelation 22:17). The theme returns, this time in the form of a plea, in the last words pronounced by Jesus on the cross. He says only this: “I am thirsty.” We may therefore situate Jesus in the middle of the way: he is both the one who satiates thirst – with the “water of life” (his life) – and the one who is thirsty for the other. He crosses and is crossed. He is at the crossroads.

Even if it is not easy, engaging with our thirst becomes indispensable, Tolentino observes, for spiritual life not to lose its basis in the reality in which personal and biographical life is anchored; rather, courage is necessary to face it head-on, without habits of seeing and free of idealizations. To acknowledge our thirst is, for these reasons, to assume a lack that constitutes us. It is the courage to acknowledge our frailty.

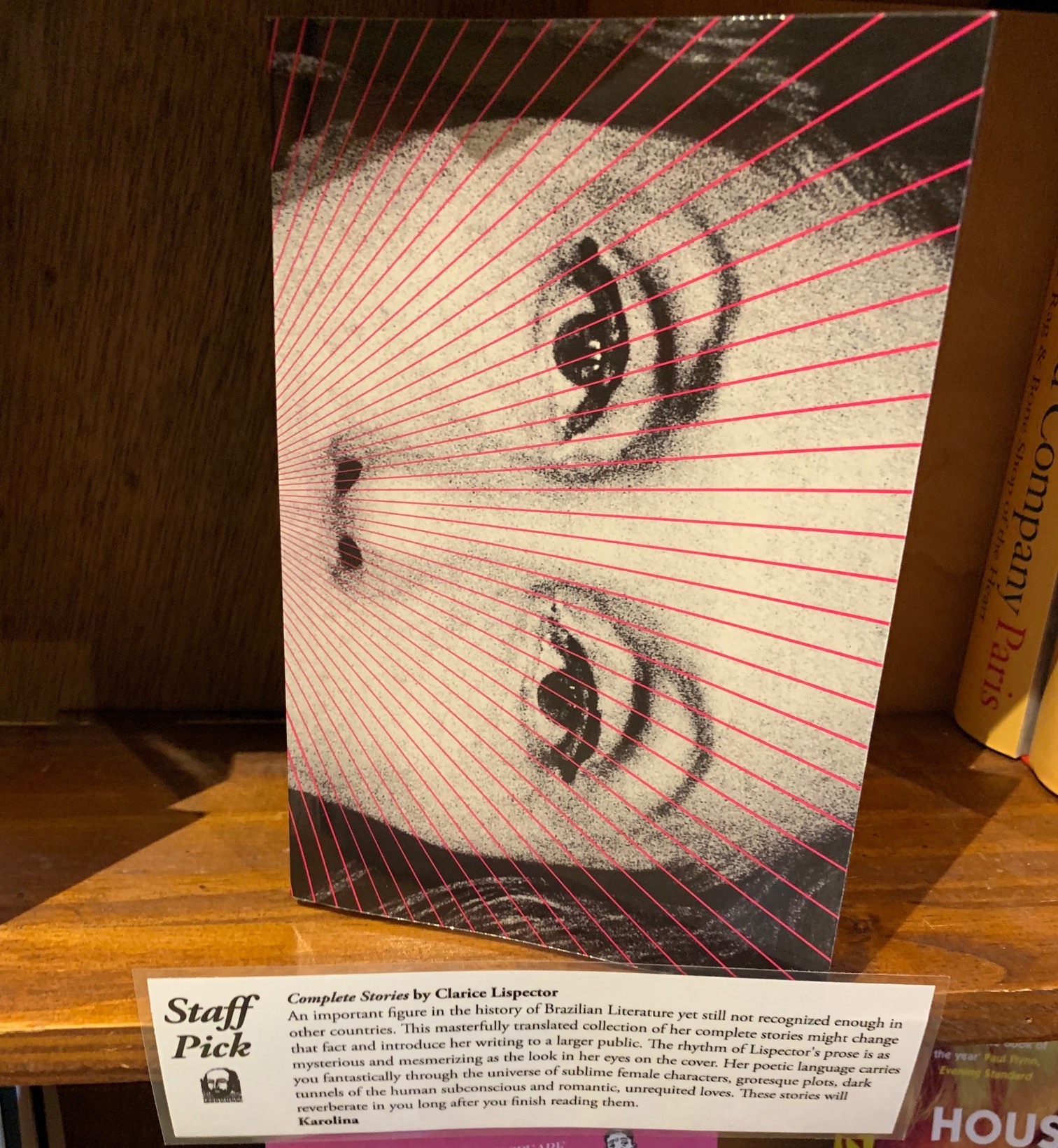

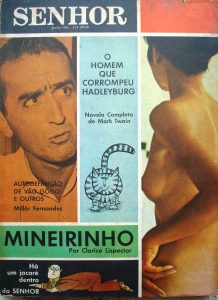

According to Tolentino, writers and poets are potential mediators among people and their thirsts, for three reasons: literature is presented without fragmented views, as an “integral metaphor of life;” it passes on knowledge that comes from concrete and not conceptual experience; and finally, in opposition to socially forged appearances, it affirms the radical singularity of existence. That being said, to illustrate the reinvigorating effect of literature in spiritual life, he quotes a long passage, of which I reproduce only a small part, from the chronicle “The Gratuitous Act,” by Clarice Lispector, which is included in the book Selected Crônicas (1984):

One afternoon, not so long ago, I was typing away under a blue sky flecked with tiny clouds, white as white could be, when suddenly I felt something inside me. A sudden weariness of this perpetual struggle. And I realized I was thirsty. A thirst for freedom had stirred inside me. I was simply weary of living in an apartment. I was weary of extracting ideas from myself. I was weary of listening to my typewriter. And then this strange, deep thirst had appeared.

It is worth observing a coincidence between the scene of Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman and that of Clarice. In both, there is a single point of reflection: it is the exhaustion that makes the thirst arise. Just as the thirst is not only for water, the exhaustion is also not only physical; it gains an existential dimension: a generalized weariness, originating from a routine that, by force of habit, tends to impair the immediate enjoyment of worldly things – and “pleasure is a being’s maximum of veracity. It is the only fight against death,” the character Angela claims, in A Breath of Life (1978).

The chronicle quoted by Tolentino corresponds with the short story “Love,” published for the first time in the book Family Ties (1960). In both, the Botanical Garden park – with its knotty trunks, flying birds, shifting and secret shadows – is the place of escape from the utilitarian everyday life, which will reconnect Clarice the author (or Ana the character) to the mystery of life and freedom itself. The rapture arises through a disturbance of the senses. In the chronicle, she writes: “Why had I chosen the Botanical Garden? Just to look. To see things. To feel them. Just to live.” The synaesthetic spiral is accentuated until the fusion with the surrounding nature and her depersonalization: “The rest was a moist green rising inside me through unknown roots.”

By chance, she encounters a fountain with a face sculpted in stone. She not only glues her mouth to that of the statue and eagerly drinks the water that spouts without stopping, but also gets all wet – “Such nonchalance seemed in keeping with the abundance in those Gardens,” she justifies. One notes that the opulence of the garden goes entirely against the founding principle of economic science, that is, the scarcity of resources, whose corollary is the law of supply and demand, a model for the fixing of prices and a driving force in the competitive game of capitalism. In the midst of such an exuberant nature, on the contrary, everything was abundant and free.

A similar situation occurs in the short story “First Kiss,” in Felicidade clandestina (Covert Joy; 1971). A young couple in the beginning of their relationship is on a bus, on what appears to be a school trip. The atmosphere is nice and they enjoy the fresh presence of each other. At a certain point, the girl asks her boyfriend if he had ever kissed another woman before her. Without further explanation, he says yes. She wants to know whom. He has a hard time answering, and in a sort of escape, he goes into a mode of contemplative suspension – “just feel —was so good.”

A sudden thirst arises. The discomfort with the lack of water keeps getting stronger: “An enormous thirst. Bigger than he was and that now seized his whole body.” The heat and the wind – which had been transformed into a “desert wind” –, although diligently endured, accentuate the boy’s unease to the same extent that his “animal instinct” intuits the freshness of the water “around the unexpected curve in the highway.” It was a matter of time, “maybe just a few minutes, maybe hours, whereas his thirst had been going on for years” —Clarice takes the thirst beyond the particular motif in the plot.

Finally, the bus stops and, before his classmates and his girlfriend, he manages to be the first to arrive “at the stone fountain.” He closes his eyes and glues his mouth “to the orifice from which the water was streaming.” He takes his first gulp: “It was life coming back, and it completely soaked his sandy insides until they were quenched.” When he opens his eyes, he notices that his mouth is fixed to the mouth of a statue of a woman and he affirms to himself, confused: “but the life-giving liquid, the liquid seed of life doesn’t come from a woman….”

In this passage, the water that spouts “from one mouth to another” is transfigured into life, just as in Jesus’ offer to his followers: “And let everyone who is thirsty come […] take the water of life as a gift.” However (and it is this that leaves the boy “confused in his innocence”), in Clarice’s story, “the life-giving liquid” is not male semen, but it sprouts from this sort of archetypal woman – materialized in the hard condition of stone – who is capable of spanning centuries and civilizations unperturbed.

In discovering the statue in its nudity, he realizes that he had kissed it. He goes into a state of disorientation proper to ecstatic experience: he finds himself perplexed, “he stood, sweetly aggressive,” with his heart beating deeply, “in a fragile balance.” Startled, he feels life transforming. We learn that the truth that emerges from within him is the end of an initiation process: “he had become a man.” Just like the stone woman, the boy also loses his individuality to indifferentiate himself in the figure of the generic man, the same sketched in charcoal next to the woman and the dog, like rock drawings, by the maid Janair in The Passion According to G.H. (1964): “On the whitewashed wall by the door — that’s why I hadn’t seen them before — were charcoal outlines, in about life size, of a nude man, a nude woman, and a dog more nude than dogs really are.”

*

To offer oneself to the risk of experience is also to place oneself in a position of vulnerability in relation to feelings of joy and sadness to which we are exposed in life. However, if the sadness persists and we are unable to contain it, our vital energy is undermined little by little. Sadness, once circumstantial in nature, becomes acedia, a state of mood that, according to Tolentino’s explanation, can be seen as an “indifference, a lack of presence and interest, a loss of the taste for life, an interior devitalization that results in a closure, making us neglect the appeal of the present.”

For Tolentino, acedia – or depression, a name used today for the illness – occurs when we renounce thirst; we abandon our desires and therefore go along with death. Although contemporary medicine has come to treat the illness allopathically – and without prejudice to this type of procedure –, it concerns a disorder of an equally spiritual origin, whose “origin is rooted in the mystery of human solitude.”

On this matter, another coincidence can be noted in the stories narrated by Clarice and by John the Evangelist. In both, there are references to the time of day in which thirst appears. It is midday, or the sixth hour – when, as a few priests from the Middle Ages believed, the figure of the “noonday demon” appeared to tempt the good spirits dedicated to moral asceticism. The fear of the religious men was not unfounded, for, as Giorgio Agamben explains in the book Stanzas, one of the notorious characteristics of melancholy was erotic disorder, which assumed, for some, such as the Benedictine monk and doctor Hildegard von Bingen, the “aspect of a feral and sadistic disturbance.”

The Italian thinker moreover observes that since Aristoteles there has been a tradition which used to associate black humor with a bent for poetry and art. Thus, an ambivalent association was established between contemplation and despondency, which based on the philosophy of the first Catholic priests, would gain relevance in the Renaissance imaginary. Melancholy would come to be a reversible sign, like two sides of the same coin, for it would allow opposing propensities under the same diagnosis. Such an identification is, for Agamben, among “the most surprising results of Medieval psychological science,” since “the recessus of the slothful does not betray an eclipse of desire but, rather, the becoming unobtainable of its object: it is the perversion of a will that wants the object, but not the way that leads to it, and which simultaneously desires and bars the path to his or her own desire.” The paradox therefore resides in the fact that desire does not cease, but the mood to seek its realization does indeed fade – desire “communicates with its object in the form of negation and lack,” he concludes.

In this game of heads or tails, how to flip to the positive side of melancholy?

Let us return to midday – “it is the central time of the day, the point that determines the transition from one part of the day to the other. It is the midpoint of time, marking a before and an after, the midpoint of the journey, the critical crossroads of life,” Tolentino affirms, investing the term with a meaning that goes beyond the strictly chronological. It is the moment in which, in the potent image of João Cabral de Melo Neto, “[…] o sol é estridente,/ a contrapelo, imperioso,/ e bate nas pálpebras como/ se bate numa porta a socos” (the sun is strident,/ abrasive, imperious,/ and strikes the eyelids as/ one strikes a door with punches; “Graciliano Ramos”, in Terceira feira [Tuesday], 1961).

Underlying the Pernambuco poet’s verses is the insurgency of an arousal of mood that, as Agamben explains, remains dormant in the melancholic state. The insidious sun of midday – the meridian demon of the medieval priests – is therefore the same that, “strident, abrasive,” contains the flawless antidote against lethargy – it strikes the fragile eyelids with the unmeasured violence of an ethical imperative: the primacy of joy.

To make the positive side of melancholy show, José Tolentino recalls the approach developed by Simone Weil of an “education of desire.” She teaches that it is necessary not to cede to the temptation of substitutions and to learn to remain “with absence, incompleteness, emptiness, and expectation.” Tolentino adds that, for Weil, “it is not our desire that reaches God. If we stay thirsty and desirous, God himself descends into our humanity to fill our desire with fullness.”

One could not help but note the similarity between the image above – of “God himself [who] descends into our humanity to fill our desire with fullness” – and the “state of grace” defined by Clarice in the celebrated chronicle of the same name, which is included in Selected Crônicas (1984). The Brazilian writer speaks of an “annunciation” – “as if the angel of life were coming to announce the world;”

[…] And there is a physical bliss which cannot be compared to anything. The body is transformed into a gift. And one feels it is a gift because one is experiencing at source the unmistakable good fortune of material existence. […] In a state of grace, one sometimes perceives the deep beauty, hitherto unattainable, of another person. […] After experiencing grace, the human condition is revealed in all its wretched poverty, thereby teaching us to love more, to forgive more, and show greater faith.

Clarice warns that grace cannot be expected: “only come[s] when desired spontaneously.” However, one may say that there is a state of opening, in which the person makes himself or herself available to receive it. Tolentino, in another book, A mística do instante (The mysticism of the instant; 2016), suggest how to do it, at the same time that he unintentionally throws light on one of the most recurrent motifs in Clarice’s work. Unlike the mysticism understood as an auscultation of the mystery (of God) in the interiority of being, Tolentino proposes a mysticism intermediated by the body and open to the imponderable of every instant. The way to access the divine thus passes through direct experience with people and the material and everyday world. It concerns a sensual mysticism, which can only be found in the present moment, which is always the middle of the way, never the end.

*

As an epilogue, I will transcribe a passage from the chronicle “Prece por um padre” (“prayer for a priest”), in Todas as crônicas (2018). Hypothetically accepting the title of spiritual master conferred by Tolentino upon her and writers in general, Clarice repeats the gesture of the Portuguese priest to his colleagues of the Roman Curia and dedicates to an anonymous priest (who had asked her to pray for him) this religious poultice against death:

One night I stammered a prayer for a priest who is dying and is embarrassed for being afraid. I said a bit to God, with some modesty: relieve the soul of Father X…, make him feel that Your Hand is given to his, make him feel that death doesn’t exist because in truth we are already in eternity, make him feel that to love is not to die, that to surrender oneself does not mean death, make him feel a modest and daily joy, make him not ask You too much, because the answer would be as mysterious as the question, make him remember that there is no explanation why a child wants a kiss from his mother, and yet he wants and the kiss is perfect, make him receive the world without fear, because we were created for this incomprehensible world and we too are also incomprehensible […].

When mysteries touch – the erotic plethora of the child kissing the mother – it means that life, beyond any understanding, pulses aimlessly – with joy.

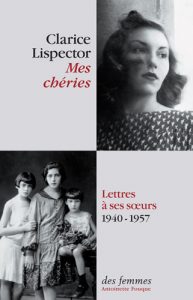

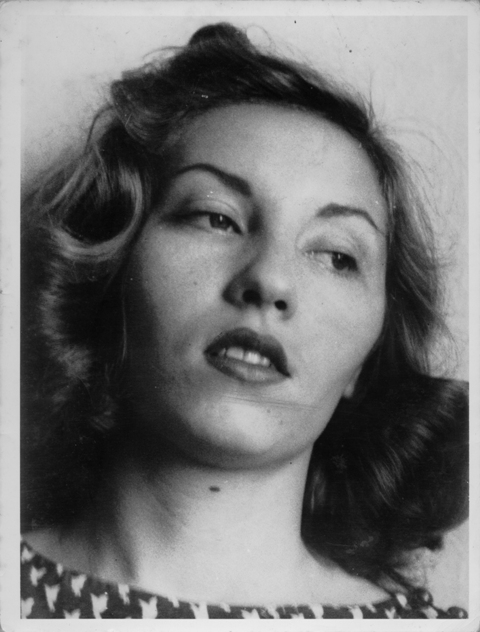

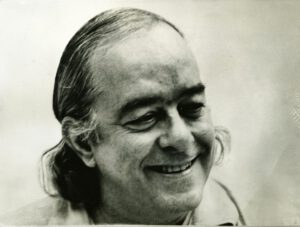

*Photo: A ten-year-old Clarice, at the Derby square garden, wears black because of her mother’s death. Recife, 1930. Clarice Lispector Collection/ IMS.