, “Becoming”: Notes on Clarice Lispector’s “secret life”. IMS Clarice Lispector, 2017. Disponível em: https://site.claricelispector.ims.com.br/en/2017/12/21/tornar-se-notas-sobre-a-vida-secreta-de-clarice-lispector/. Acesso em: 26 July 2024.

In this year in which we commemorate The Hour of the Star, the entry of Clarice Lispector and her alter ego (one of many), Macabéa, into the “própria profundeza (…) – a floresta”, the profusion of factual explanations for this or that character, narrative element or writing situation, in bonding and plastering a work already marked by biographical reading, one seems to lose sight of the essential lesson repeatedly stated by this writer and her writing known precisely for the rarity of plot, of facts. If the formulation of such a lesson appears in Agua Viva (“Não vou ser autobiográfica. Quero ser ‘bio’”), it is in the “Explanation” of the opening of The Via Crucis of the Body that it manifests (a key term in Clarice’s poetics) itself in all its radicalism. The very unmarked position in relation to the other thirteen texts that comprise the volume, which makes it impossible to distinguish graphically or by means of a paratextual element whether it is a preface (by the author) or already a fiction (by a narrator) is reinforced by what “Explanation” says: “É um livro de treze histórias. Mas podia ser de quatorze. Eu não quero. Porque estaria desrespeitando a confidência de um homem simples que me contou a sua vida. Ele é charreteiro numa fazenda. E disse-me: para não derramar sangue, separei-me de minha mulher, ela se desencaminhou e desencaminhou minha filha de dezesseis anos. Ele tem um filho de dezoito anos que nem quer ouvir falar no nome da própria mãe. E assim são as coisas”. The fourteenth story, told in the same gesture in which its omission is announced – an unconfident confidence –, thus resembles “the fifth story” and eponymous titled story in The Foreign Legion: the last, or first, of the stories is the story of the making of the stories, not only implying (folding inward) the life in the work, but also explaining (folding outward) the fiction in reality. In this sense, it is worth recalling that, according to the explanation, the genesis of The Via Crucis came from a commission for “three stories that (…) really happened” (emphasis added), and those are, according to the author (or narrator), “Miss Algrave”, “Via Crucis” and “The Body”, the three parts of the book that are furthest from the proposal, for they consist in, first of all, the parodic rewriting of other texts: in order, mystical experience of Catholic women, the incarnation of Christ, and a short story by Edgar Allen Poe, “The Tell-Tale Heart”, which Clarice had already translated (or rather, rewritten, giving it the title “The Denouncing Heart”). Like “Useless Explanation”, from “Back of the Drawer”, the second part of The Foreign Legion, which gained autonomy in Not to Forget, the “Explanation” complicates more than it supplies a key to reading for the relation of life to literary work and for the genesis (the birth) of fiction in reality – which was already foreshadowed in the book’s epigraphs, mixing Biblical passages and one attributed to “a character of mine still without a name” and another “I don’t know whose it is”. Thus, on the one hand, Clarice makes of a fiction of Poe (or takes it as) a story that really happened (what is written has happened, what one writes happens), in a paradoxical literary movement of deliteraturization, masterfully elucidated by João Camillo Penna, and that appears already in Near to the Wild Heart, when Steppenwolf, a character in the book of the same name by Hesse, and therefore a literary reference, figures as a life memory of Joana’s. On the other hand, in a game with the editor’s commission, she inserts into this book of stories, of fictions, three other stories (“The Man Who Showed Up”, “Day After Day” and “For the Time Being”) that sound, by the diction and resumption of dates and facts mentioned in the “Explanation”, like non-fiction, in every regard close to Clarice’s chronicles. That is, the writer at the same time complies to the letter and doubles the bet placed by the editor to fictionalize real facts: indeed, from the very opening of the book, as we have seen, life becomes fiction, but what is fictionalized (or realized) are not only certain facts, but the writing of the book itself, the commission and its realization, the life of the writer and of writing, in sum, the very relation between life and literary work, reality and fiction. It’s as if, for Clarice, literary fiction, the “as if”, constituted a two-way street, through which the non-existent gains life only to the degree that ‘real life’ becomes unreal, that is, it occurs from a recreation of the given, as we can see in this famous passage in which the birth of writing coincides with the non-birth (death) of the writer, or rather, with reciprocal transformation (and intersection) – a face-to-face – of reality and of fiction: “Escrever é tantas vezes lembrar-se do que nunca existiu. Como conseguirei saber do que nem ao menos sei? assim: como se me lembrasse. Com um esforço de memória, como se eu nunca tivesse nascido. Nunca nasci, nunca vivi: mas eu me lembro, e a lembrança é em carne viva” (emphasis in the original).

The “Explanation” appears to poetically formulate a much sought after and worked for solution, combined and of financial origin, to a double problem which plagued her: the necessity to write crônicas every day, and, therefore, to ‘talk about oneself’, take

If, as Joana states, “nada existe que escape à transfiguração”, this feminine excess that is in everything that exists and that is confused with existence itself as a transformation (including, and this is the point, transformation of what is the female), the problem of gender shows itself right away as a problem of genre, with the progressive transfiguration of the narrative form of the novel, which, starting in the third person (unmarked position, i.e., masculine, and, in a certain sense, isomorphic to the divine omniscience of the phallic, Father creator ex nihilo) and with the father writing, gradually he is being contaminated by the female first person, the voice of Joana, who gives the last enunciation. The movement of formal transfiguration, the feminization of the narrative form, is not restricted to Near to the Wild Heart, but traverses through Clarice’s novels, having as its apex The Passion According to G.H., now entirely in the first person, with the protagonist narrator facing the challenge of not relying more on a “third person” and on the eye that “vigiava a minha vida” (the omniscient third person?), and, to that end, and in return, inventing a male path: from a he that creates and talks about a she, we pass to a she that creates and talks about a he. In Agua Viva, after this strange body (and, for this reason especially important) that is An Apprenticeship, she resumes the structure of G.H., but now free of any plot other than the writing itself and her desire to capture the “instant-already”, which is the “semente viva”, the “instantes de metamorfose”, the exact moment of transformation, of becoming oneself. It’s not startling, therefore, that it is not presented as a novel, but as “fiction” (or as “thing”, as Hélio Pólvora disparagingly—but attuned to Clarice—classified it in his opinion of Agua Viva for the National Book Institute). But as nothing in Clarice escapes transfiguration, the final two long prose works, The Hour of the Star and A Breath of Life (also not “novels”, but “novela” and “pulsations”, respectively), produce a further twist: in them, we find ourselves facing first-person male narrators writing books about (creating) female characters, in a gesture packed with critique of the criticism that Clarice – and women’s literature in general – suffered. Think, for example, of the old flaw of sentimental or intimate literature, that is, the accusation of always talking about oneself, and how Rodrigo S.M., “the most cynical narrator ever created by Clarice Lispector”, according to Ítalo Moriconi, cannot help but project himself and his stereotypes onto Macabéa, to the point where she sees his image when looking in the mirror – and this coming from an engaged writer, documentary, interested only in “fatos sem literatura”, and who complains that “escritora mulher pode lacrimejar piegas”. And, to talk about the “nordestina amarelada”, about the “cadela vadia”, in the name of Macabéa, Rodrigo S.M. must necessarily attribute to her not only the total absence of a voice and consciousness, as even, by narrative means, a name. On the other hand, however, it is emblematic that the final movement of A Breath of Life resumes that of Near to the Wild Heart, with Ângela, a character, coming from fiction to the world, and the Author losing the words, in an inversion of the fate of another creature, Macabéa:

“E agora sou obrigado a me interromper porque Ângela interrompeu a vida indo para a terra. Mas não a terra em que se é enterrado e sim a terra em que se revive. Com chuva abundante nas florestas e o sussurro das ventanias.

Quanto a mim, estou. Sim.

‘Eu… eu… não. Não posso acabar.’

Eu acho que..”

In a crônica that confronts this series of issues– the classification of her books, in particular GH, the form of her narratives and the rarified plot, and the relation between life and fiction –, Clarice exposes in a theoretical key the coming into the world of Ângela (and other characters, such as Joana, since Near to the Wild Heart concludes in media res, with the protagonist traveling, leaving the bonds of the family and the narrator to another, unknown place): “O que é ficção? é, em suma, suponho, a criação de seres e acontecimentos que não existiram realmente mas de tal modo poderiam existir que se tornam vivos”. It’s not a matter of proximity or appearance of truth or reality (an internal or external verisimilitude), but of an entry into life: fictional creation names, for Clarice, a certain intensification in the way of being of the possible or the nonexistent (“de tal modo”), which makes it – transforms it– alive. In this sense, the Spinozist conception intoned by Joana, “Tudo é um”, should be read in the broadest sense possible – everything participates of the same substance, including fiction and nonexistent beings: “Tudo é um, tudo é um…, entoara. A confusão estava no entrelaçamento do mar, do gato, do boi com ela mesma. A confusão vinha também de que não sabia se entrara ‘tudo é um’ ainda em pequena, diante do mar, ou depois, relembrando. No entanto a confusão não trazia apenas graça, mas a realidade mesma. Parecia-lhe que se ordenasse e explicasse claramente o que sentira, teria destruído a essência de ‘tudo é um’. Na confusão, ela era a própria verdade inconscientemente, o que talvez desse mais poder-de-vida do que conhecê-la. A essa verdade que, mesmo revelada, Joana não poderia usar porque não formava o seu caule, mas a raiz, prendendo seu corpo a tudo o que não era mais seu, imponderável, impalpável.” If everything participates in the same substance, if the difference between things is not of nature, of essence, but of manner, of form, then there follows a continuity not only between human and animal, but also between the organic, live, and the inorganic, supposedly dead, and, moreover, between existing and non-existent beings: it is thus a matter of questioning the prerogative of human exceptionality, of biological life and ontological superiority of the currently existing, and, at the same time, since everything participates in the same substance, changing only its form, to postulate the universal possibility of metamorphosis and transfiguration, in short, of life. “Tudo é um” means that everything can be modified, that everything is alive – including, and this is the extension we want to emphasize, the fictional beings, who are as alive as existing beings. Following the Shakespearean maxim – “We are such stuff as dreams are made on” –, Clarice seems to postulate a radical monism, which can be seen in a series of her formulations or of her characters in which creation doesn’t refer to an other whose reality or life is inferior, as when G.H. states: “Terei que fazer a palavra como se fosse criar o que me aconteceu? Vou criar o que me aconteceu. Só porque viver não é relatável. Viver não é vivível. Terei que criar sobre a vida. E sem mentir. Criar sim, mentir não. Criar não é imaginação, é correr o grande risco de se ter a realidade”. Perhaps this explains why the experience of the “thing” is always accompanied by an experience of language in her fictions, because, when entering the “bio” before the biographical, the “neutral”, “it”, the “raw material”, the “forest”, the “forbidden fabric of life”, the zone prior to individuation and separation of genders, where “She/he” reigns, the “He/She” of Where You Were at Night, the Clarice characters feel the need to write, fictionalize, for they see, like Joana, their bodies connected by a root to everything that is no longer theirs– all the other things, all the other beings, among them the non-existent. “Having the reality” of the experience of the oneness of the world therefore implies creating, as a gesture of becoming alive, of intensifying a way of being that normally appears not only dead, but nonexistent. Thus it is not by chance that, in Agua Viva, the narrator-protagonist, after experiencing the “state of grace”, describing it as “se viesse apenas para que soubesse que realmente se existe e existe o mundo”, states that “depois da liberdade do estado de graça também acontece a liberdade da imaginação. (…) A loucura do invento”. The “state of grace” comes only to know that one really exists and the world exists – and that, among them exists the non-existent, which fiction has the power to make alive.

An Apprenticeship or The Book of Delights opens with the protagonist Dori facing a situation of extreme anguish, fictionalizing, in a succession of “make-believe” described as “os movimentos histéricos de um animal preso”, which “tinham como intenção libertar, por meio de um desses movimentos, a coisa ignorada que o estava prendendo”. This transvaluation of a typically (stereotypically) feminine scene, associating, as in Agua Viva, creation and freedom, brings us to the true Clarice date, or rather, Clarice time par excellence, between two dates, possibly invented in the writing of The Via Crucis of the Body. If “Explanation” states that “Today is May 12, Mother’s Day”, the date on which the three stories that “really happened” would have ended, the “P.S.” that supplements it (or rewrites) and on which other stories of the volume would have been written is dated another today, after the “domingo maldito”: “Hoje, 13 de maio, segunda-feira, dia da libertação dos escravos – portanto da minha também”. One can read this sequence, this association or succession between motherhood and freedom in two ways, not necessarily contradicting each other. On the one hand, as the liberation from slavery of the characters, especially the feminine ones, from the social, family role, epitomized in reproduction, in maternity – the transition from mother to liberated. In this sense, it would be about the radicalization of the movement that intensifies in Clarice’s writing starting with what José Miguel Wisnik called the separation trilogy– Family Ties, The Foreign Legion and The Passion According to G.H. In it, family bonds, socially familiarized, not only unite, but also bind, arrest, serving as instruments of domestication that allocate each to their place. Yet, on the margins of the familiar, the edges of the ties of the domesticated, a series of figures that will dominate Clarice’s later fiction begin to emerge: crazies, servants, animals (hens, dogs, cockroaches, horses, etc.), “natural” spaces domesticated in the city, surrounded by it (gardens – private, zoological or botanical), etc. Like a true foreign legion – in a sense completely opposite to the military formation with that name –, these figures increasingly gain more and more the center of the scene, questioning and revealing the violence of the domesticated and domesticating relations to the point where, in The Via Crucis, multiplicity can longer be alien to the family body of that time– gays, lesbians, transsexuals, prostitutes, nuns and widows full of carnal desire, beggars, in short, “everything that has no worth”, to use the words of a worthless politician. Thus, for example, the duo of short stories “Monkeys” and “The Smallest Woman in the World”, articulating racism and speciesism, brings out the role of violent exoticism, even when pious, which is at the base of the process of familiarization (of humanization) in our society. Such questioning, however, is not limited to a denial of the given, a reverse affirmation; rather, it seeks to convert the affirmation into a question, in what appears to be a movement that runs through Clarice’s writing: “Este livro é uma pergunta”, claims Rodrigo S.M.; “Escrever é uma indagação. É assim: ?”, we read in A Breath of Life; “sou uma pergunta”, says the narrator in Agua Viva, a phrase that is also the title of a crônica; and, to offer just one more example, the strongest of them: “O único modo de chamar é perguntar: como se chama? Até hoje só consegui nomear com a própria pergunta. Qual é o nome? e este é o nome.” It is thus not only about denying existing ties, or of affirming others in their place, but to open space for the experimentation with other relations– that is why liberation is only the first step in a movement of inquiry that cannot stagnate at an affirmation, at a name: “Liberdade é pouco. O que eu quero ainda não tem nome”. Take the short story “The Foreign Legion”. In it, we are faced with a family configuration that is at minimum strange. The members of the narrator’s own family are not named and hardly appear. Who occupies the place of prominence, in the first moment, is a chick who, terrified, makes the children ask their mother that she be the mother of that animal, of someone who doesn’t properly belong to the family, and not even to the human race – a motherhood role that the narrator says she doesn’t know how to fulfill. It is this “unfamiliar” scene (to use a term that appears three times in Family Ties, and is a possible translation for Freud’s Unheimlich) that makes her remember another, the familiarity with Ophelia, the daughter’s neighbor and another stranger to whom she was a mother. If, on the one hand, the narrator seems to hold a certain attraction for her, to the point where the child visits her every day, on the other hand, the relationship seems socially inverted, for it is Ophelia who behaves like an adult, as the embodiment of obedience to behavioral social norms (the theme will reappear in a tragic way in “The Obedient Ones”), it’s up to the hostess to indeed bow and define the tie between them paradoxically: “já me tornara o domínio daquela minha escrava”. The turning point comes when Ophelia hears a chick (another) in the kitchen, and the narrator allows her and encourages her to play with the animal, which she ends up doing, against all the rigidity imposed on her by her own family. It’s not surprising that in the description of the event again we come across an image that has already become familiar: “A agonia de seu nascimento. Até então eu nunca vira a coragem. A coragem de ser o outro que se é, de nascer do próprio parto, e de largar no chão o corpo antigo. (…) Já há alguns minutos eu me achava diante de uma criança. Fizera-se a metamorfose”. It is in a relationship that is not exactly maternal that motherhood gains an opening of meaning, that new ties between the narrator and Ophelia, between this girl and the world and with herself, can be experienced: here, motherhood (‘improper’) designates the opening of the door to disobedience, so that one can get out of family ties, so that one can make contact with the stranger, and thus modify oneself, “be the other that one is”. Thus we can return to the succession of dates of “Explanation” and see them in another way, complementary to this first: motherhood as a liberation from given relationships, possibility of recreation of the given, including motherhood itself, since the most maternal figure (including literally) of The Via Crucis of the Body is the transsexual Celsinho/Moleirão, “mais mulher que Clara”, her friend (‘biologically’ a woman) and rival.

The strength and uniqueness of Clarice’s conception of fiction, and its relation to life, lies in this attention to those who/that are on the margins, as if the power to make fiction alive, its power to liberate, were related to the “power-of-life” of the radically other– and “attention” is another of the crucial words, also associated with the feminine, with her writing: “Lóri era uma mulher, era uma pessoa, era uma atenção, era um corpo habitado olhando a chuva grossa cair”. In her beautiful text on The Hour of the Star, Hélène Cixous points out the minutia of this attention and its consequences: “The greatest respect I have for any work whatsoever in the world is the respect I have for the work of Clarice Lispector. She has treated as no one else to my knowledge all the possible positions of a subject in relation to what would be “appropriation”, use and abuse of owning. And she has done this in the finest and most delicate detail. What her texts struggle against endlessly and on every terrain, is the movement of appropriation: for even when it seems most innocent it is still totally destructive. Pity is destructive; badly thought out love is destructive; illmeasured understanding is annihilating. One might say that the work of Clarice Lispector is an immense book of respect, book of the right distance. And as she tells us all the time, one can only attain the right distance through a relentless process of de-selfing, a relentless process of deegoization. The enemy as far as she is concerned is the blind self.” Thus, for Clarice, paying attention to the other would require a “depersonalization” or “objectification” of oneself, the entry into the neutral, the “non-birth” of oneself, movement without which her conversion into an “inhabited body” is not possible, the “Involuntary Incarnation” a story/crônica speaks of and that seems to be a good name for fiction according to C.L.: “Às vezes, quando vejo uma pessoa que nunca vi, e tenho algum tempo para observá-la, eu me encarno nela e assim dou um grande passo para conhece-la (…) Já sei que só daí a dias conseguirei recomeçar enfim a minha própria vida. Que, quem sabe, talvez nunca tenha sido própria, senão no momento de nascer, e o resto tenha sido encarnações”. Exemplified by the incarnation in a missionary and later in a prostitute (an always present pairing), the operation, which I have called oblique, often occurs before, or in relation to, figures of an extreme otherness, especially animals. It is a matter of adopting the perspective of the other and, in this way, estranging oneself (hence the importance of the intensity of the difference), as in “Dry Sketch of Horses” (“E veria as coisas como um cavalo vê”), or in “In Search of a Dignity”, in which the perspective of inversion is fully enunciated: “Ulisses, se fosse vista a sua cara sob o ponto de vista humano, seria monstruoso e feio. Era lindo sob o ponto de vista de cão. Era vigoroso como um cavalo branco e livre, só que ele era castanho suave, alaranjado, cor de uísque. Mas seu pelo é lindo como a de um energético e empinado cavalo. Os músculos do pescoço eram vigorosos e a gente podia pegar esses músculos nas mãos de dedos sábios. Ulisses era um homem. Sem o mundo cão” (The children’s book Almost True will pull this thread even further, as it is narrated by the “same” dog Ulysses, Clarice’s life companion, and it is up to her to transcribe or translate his barking into writing). However, the movement does not end there: we would not be faced with a true birth, a true becoming, a transformation, if such an incarnation were not to establish a relationship with life, were not to become alive itself, we would not be changed, it would not make us reborn. It is necessary, therefore, that the perspectivist transformation be a way of looking at each other through the eyes of the others and that we be looked at by them, not only to see the world through the eyes of the others, but also to see ourselves by this gaze, see ourselves in another way, changing us. At least, this seems to be the “experiência maior” which Clarice speaks of, and that her fictions keep searching for: “Eu antes tinha querido ser os outros para conhecer o que não era eu. Entendi então que eu já tinha sido os outros e isso era fácil. Minha experiência maior seria ser o outro dos outros: e o outro dos outros era eu. “A experiência maior”, while becoming another from contact with the other is not reduced to being the others (an experience not flush with reverse egotism); rather, it constitutes an experiment of subjectivity anchored in transfiguration, through which, traversing the non-birth of oneself and the birth of the other in us, we access the “terra em que se revive” of which A Breath of Life speaks, where we recreate– or we are recreated. Fiction makes the other alive in us, to make our life another. It provides the liberty to question oneself and one’s ties to the world and to inquire of other relations, for which we do not yet have names, for which the question is the only possible name.

Starting from a mirrored formulation of A Breath of Life, “A sombra de minha alma é o corpo. O corpo é a sombra de minha alma”, the young scholar of Clarice’s works Letícia Pilger said that the author’s relationship with the posthumous book could be defined in an analogous way: indeed, the fictional work is the shadow of Clarice’s life, provided we take the reciprocal as true, namely that Clarice’s life is also the shadow of her fiction. After all, to paraphrase Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, if everything, including fictional beings, is alive, then life is also a fiction, is something else – everything is one (becoming).

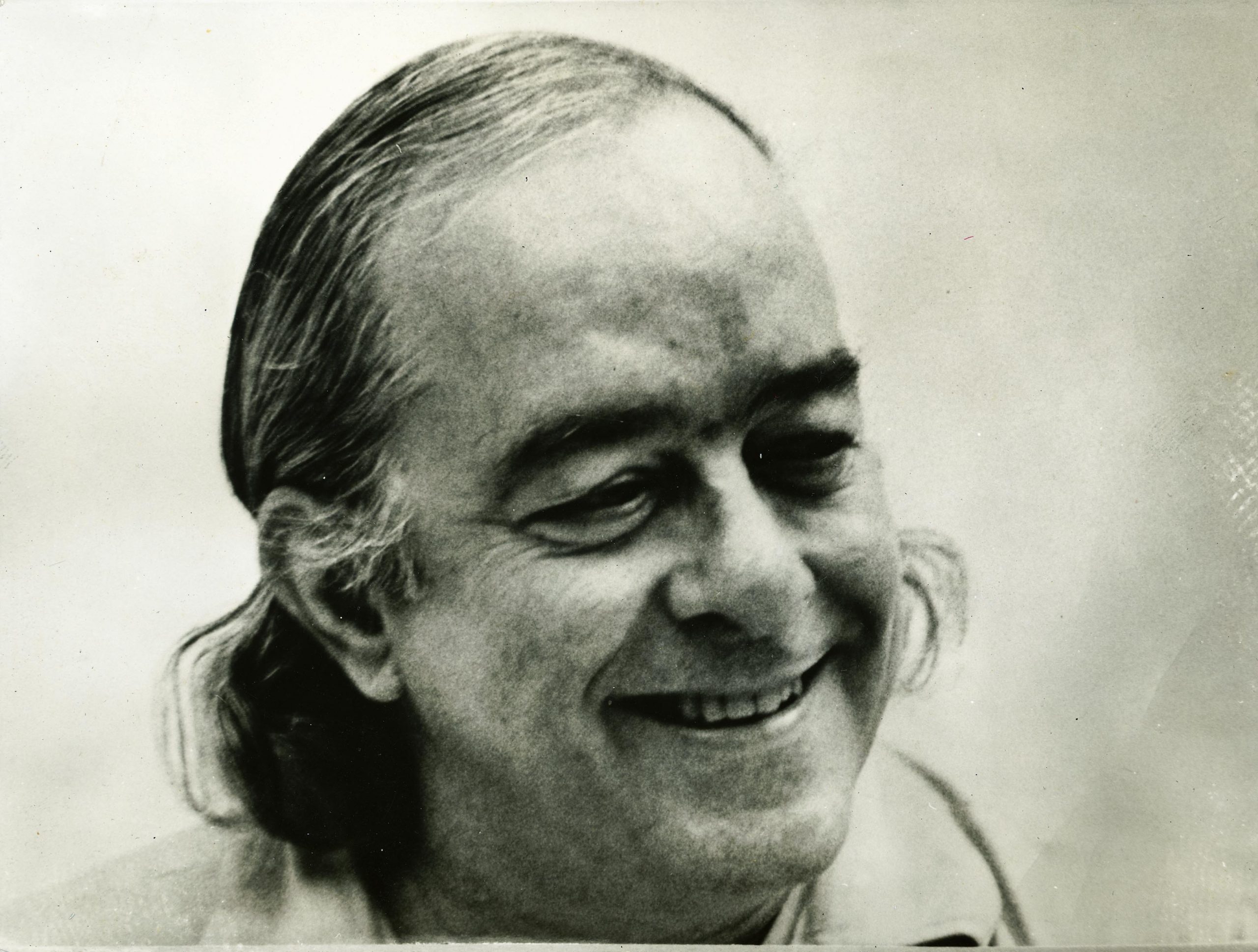

Alexandre Nodari is Professor of Brazilian Literature and Literary Theory at the Federal University of Paraná, where he is also a collaborator in the graduate programs in Humanities and Philosophy. He is also editor of the periodical Letras and coordinator of SPECIES – speculative anthropology research group: http://speciesnae.wordpress.com.